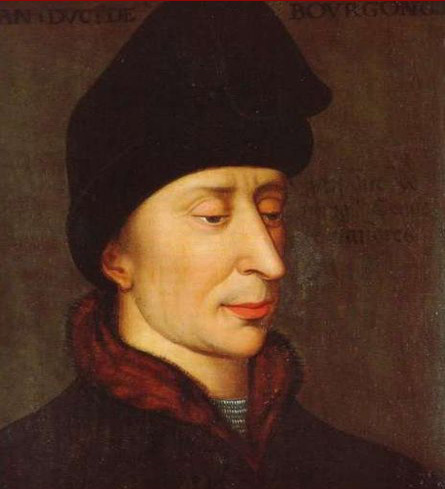

“A Game of Thrones soap opera where everything is true,” says one critic. “A history book that reads like a thriller,” says another. On the one hand, these observations shed less light than they seem to. Martin and his ilk borrow a lot from medieval European history, so the affinities between those good stories and the ones where “everything is true” shouldn’t surprise us. But on the other hand, there is something special in Van Loo’s impossibly habit-forming history of the Dukes of Burgundy. This is partly down to the liveliness of the writing itself—deadened only a little by heavy reliance on TV-documentary clichés, which might be the fault of the translator—and to the dynamism of the book’s shifts between large and small scales of time and interpersonal drama (about which more later). But all this “like a true Game of Thrones” stuff also clearly has to do with how much of a good, compelling, naturally story-shaped arc there is to the lives of the four key Burgundians, the heroic Philip the Bold (1342-1404), the violent, lionhearted would-be crusader John the Fearless (1371-1419), the extravagant, statecrafting political strategist Philip the Good (1396-1467), and ultimately the tragic end in and of the troubled Charles the Bold (1433-1477).

The book is an impressive study in scale. First, there’s the wide variance in the handling of time. What’s billed as a history of “1111 years and 1 day” is ultimately a book about one century and four people. It devotes an opening section to the “Forgotten Millennium” from 406 to 1369, a kind of stage-setting 40,000-foot overview, and at the other end are sections devoted to a “Fatal Decade” (1467-77), a “Decisive Year” (1482), and ultimately a single “Memorable Day” (20 October 1496). But the middle section is where most of the action is: the “Burgundian Century,” 1369-1467, chronicling the expanding and contracting duchy and the ambitions and atrocities of its rulers. Van Loo observes this history at scales that allow for different levels of detail, cutting across centuries in one chapter and devoting the next to a detailed account of a single evening, etc. The description of the lavish feast on 17 February 1454, essentially a Crusade recruitment event masterminded by Philip the Good, is an especially absorbing instance of the latter. This is a big part of what makes the book “read like a thriller”; to be fair to Van Loo, even when he is dramatizing personal conversations and individual emotional reactions to things, he relies heavily on the work of contemporary chroniclers (who might well have been fabricating a great deal themselves, of course). These moments aren’t mere modern speculations or whole-cloth inventions. But they are the product of a novelistic imagination, and they’re dramatized with careful attention to pacing, suspense, foreshadowing, etc., with the result that the book really is surprisingly hard to put down.

Just as so many have loved A Song of Ice and Fire without having any investment in the history of the Wars of the Roses, a reader of Van Loo’s history is apt to find it propulsive and engaging without any knowledge of or even interest in the Burgundy of the Late Middle Ages. I was one of those readers: visiting Bruges a few weeks ago, I got chatting with a local on a bridge over the Groenerei one day and he recommended this book to me so heartily that I figured there must be something in it and promptly sought it out. (Only travellers of a certain sort will take the recommendation of a 600-page book of late-medieval history and begin toting a brick-thick hardcover all around the Low Countries in a carry-on already overstuffed with books; I am apparently this sort of traveller.)

The abiding claim here is basically that Burgundy was the seedpod out of which grew not just the present makeup of the Low Countries but indeed much of the rest of the modern European political landscape. I wondered at the outset if this wasn’t perhaps very slightly overstated. But as events unfold, the world-historical dimensions of this period and these figures start to come into view. At one point, in an anecdote about the pre-printing-press bookbinding industry that flourished in wealthy Flanders in the 1460s, suddenly in walks Gutenberg himself. Earlier, amidst all the upheavals of the Hundred Years’ War, we and Philip the Good suddenly find ourselves face to face with Joan of Arc. In the 1490s, in sails Christopher Columbus. And so on—on the historical who’s-who goes. There’s absolutely justification for Van Loo’s claims about Burgundy’s ramification and influence (which won't be news to those who do come to this book with knowledge of the subject, I'm sure). With Charles the Bold and the Burgundians’ eventual entanglement with the Habsburgs and the unification of the Low Countries with Austria and Spain, one sees again and again something special and oddly decisive about this period. As Lenin said, “There are decades when nothing happens; and there are weeks when decades happen.” Far more than a century of history seems to happen in Flanders, in Brabant, in Holland, Hainault, Zeeland, in France, in England, and in the Holy Roman Empire, etc., between the 1360s and the 1460s.