What do you think?

Rate this book

768 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 2001

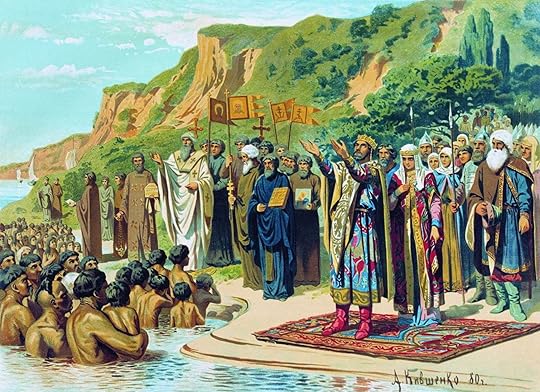

“Having taken his decision, he acted forthrightly, even harshly. He demonstratively smashed the pagan idols: Perun was dragged by horses down the hill, beaten continuously by twelve men with rods, and dumped in the Dnieper. He commanded besides that the citizens of Kiev should betake themselves to the riverbank to be baptized by immersion: “Whoever does not turn up at the river tomorrow, be he rich, poor, lowly, or slave, he shall be my enemy!” ~1: Kievan Rus, The Mongols, and The Rise of Muscovy, page 38.

The Baptism of the inhabitants of Kyiv, attended by Prince Vladimir the Great, painted by Aleksey Danilovich Kivshenko.

“Instead, he had inaugurated a tradition that in order to unite and mobilize, Russian rulers had to be harsh and overbearing, even to violate God’s law, to the extent of risking disunity and demoralization, and of undermining the ideals which the monarchy itself professed.” ~2: Ivan IV and The Expansion of Muscovy, page 126.

“Peter might be accused—and was—of putting the cart before the horse, of promoting abstruse scientific research while the overwhelming majority of the population could not even read.” ~4: Peter the Great and Europeanization, page 208.

The Beginning of Autocracy, painted by Ilya Zorkin. Notice that Peter the Great, upon his accession as the sole Tsar, was still wearing Muscovite traditional clothing which he eventually discarded for the more “modern” attire based on the European model.