What do you think?

Rate this book

192 pages, Hardcover

Published October 29, 2024

"...I had known Stanley Prusiner for some years and had been watching the progress of his laboratory in characterizing this highly unusual “microbe.” I had also seen the tremendous amount of skepticism raised by his outlandish claim that it lacked genes, that it was an infectious protein. Stan’s issue that morning was what to call this unique infectious agent. He had two candidates, he said: “piaf” and “prion.” I forget what piaf stood for, but I said that the name was already taken by a very popular French singer. Fine, he said, in any case he preferred prion, a contraction of protein and infection. I agreed. What I did not say was that prions in my native French tongue means “let us pray,” and that if he persisted with his claim of an infectious protein, he would need prayers. As we know, Stan was right, and for the discovery of prions he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1997."

"The human brain contains approximately eighty-six billion neurons, which communicate through close to quadrillion (10x15, or one followed by fifteen zeroes) synapses. Those are astronomical numbers. It is difficult, or even impossible, for us to construct a mental image of a quadrillion objects. It is too large. For example, one hundred billion is the number of stars in our galaxy, the Milky Way. The number of synapses in our brain is equivalent to the number of stars in ten thousand Milky Ways!"

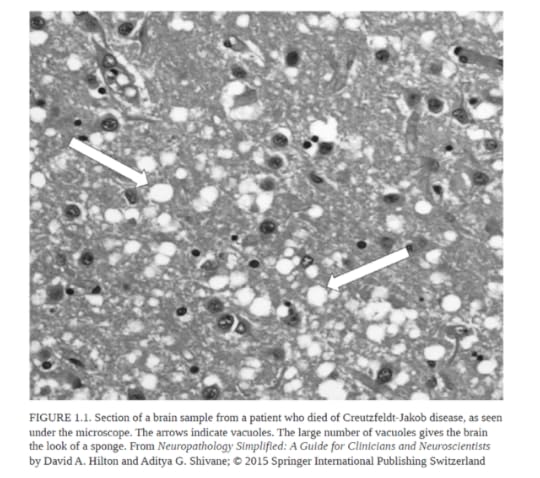

"...Because these diseases all cause millions of tiny holes, called vacuoles, in the brain, they are grouped under the name spongiform encephalopathies—diseases that, under the microscope, give the brain the look of a sponge. All of them are caused by a protein called PrP, short for prion protein."

"But there are also “good” prions! An early and most surprising discovery was made at Columbia University in the laboratory of Eric Kandel. This group had been doing pioneering work on the molecular mechanism of memory using a simple model animal, a sea slug named Aplysia. After much work, they concluded that a protein with prion properties, but again different from PrP, was involved in memory storage in this animal. They went on to show that the same protein was involved in memory in the fruit fly and in mice. And there are more and more “good prion” proteins being discovered. It turns out that prion proteins appeared very early, maybe even at the very beginning of the evolution of life on this planet. We will discuss later how they help primitive organisms such as yeast to adapt to changes in their food environment. This field is young, fast-moving, and not devoid of controversy. The nomenclature is not yet settled. Some prefer to use the name prion only for PrP, the protein that causes kuru and the other spongiform encephalopathies. They call the others “prion-like proteins” or “prionoids.” Maybe it is time to resurrect piaf for those! But for the sake of simplicity, I will call all of them “prion proteins” or “prions.”