A couple of years ago, Admiral James Stavridis, a retired naval officer who served as Supreme Allied Commander of NATO and commander of U.S. Southern Command, and Elliot Ackerman, a longtime author and journalist, released 2034: A Novel of the Next World War. As a work of fiction, it wasn't much, but a book co-authored with someone like Admiral Stavridis' credentials depicting how a conflict with China could escalate into a global war and how such a war would be fought made it worth reading. Through the cover of fiction, the authors highlighted China's significant advancements in military technology and challenged the notion of the U.S. military as an unbeatable force. I recommended the book then, and I continue to recommend it now. However, you can skip the sequel.

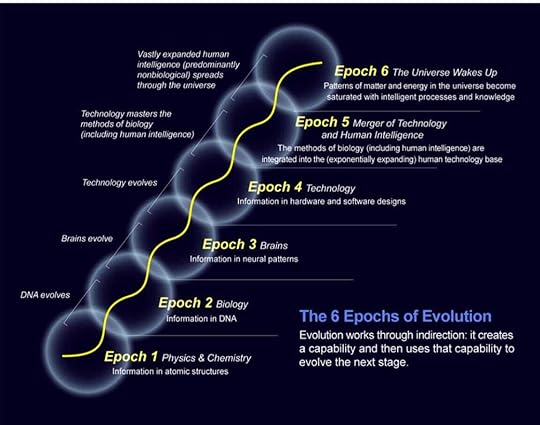

2054 picks up on the same story twenty years into the future. Sarah Hunt, the Navy captain who served as the main character in the first book, is now dead from an apparent suicide, and Julia Hunt, her stepdaughter and a Marine major, takes her place as the book's protagonist and moral compass. Whereas 2034 was a work of speculative fiction dealing with realistic military technology, 2054 takes a hard turn toward science fiction, delving into a quintessential sci-fi theme: the singularity. The book borrows heavily from the work of the scientist and non-fiction author Ray Kurzweil and makes him a central character in the story. No longer grounded in Admiral Stavridis' insight into the near-term dangers of an emerging Chinese superpower, the book is forced to stand on its own as a work of pure literature, leaving the heavy lifting to Mr. Ackerman. I'm unfamiliar with Mr. Ackerman's other works, and perhaps he's out of his element here, but this is a bad book.

There’s probably no greater literary challenge than creating a world thirty years in the future on the same planet we all currently inhabit, explaining why so much science fiction is set in places far away and the distant future. The authors can’t decide how the world will look and function thirty years from now, mixing references to sub-orbital plane flights and telecommunications conducted through holographic images projected by embedded computer technology with references to laptop computers and landlines. We also discover that people in 2054 are curiously preoccupied with the 2020 coronavirus pandemic, placing more emphasis on it than most people today. And one of the main storylines centers on a power struggle between the major political parties that results in an insurrection in the U.S. Capitol building, which sounds like some alternative version of the January 6, 2021 riots and suggests the authors did little more than extrapolate yesterday’s headlines thirty-three years into the future.

Unfortunately, there's no redemption in the book's plot, character development, or dialogue. The authors tell the story as a futuristic political thriller with predictable characters doing predictable things while dealing with issues that, despite their earth-shattering significance, barely managed to hold this reader's attention. In one scene, a character who feels betrayed by her lover responds to his arrival in her holding cell by slapping his face. In another, a character greets a visitor with the line, "To what do I owe the pleasure of this visit?" Maybe I don't run in the right circles, but I've never known real people who behave or speak this way, and I suspect such behavior and speech are even less likely thirty years from now.

The biggest disappointment here is what could have been. Instead of expanding the previous story by creating storylines in the more challenging-to-predict mid-21st century, the authors could have focused on the near future and addressed issues and concerns more relevant to our time.

Admiral Stavridis's recent Wall Street Journal essay, "Drone Swarms Are About to Change the Balance of Military Power," provides an excellent starting point for such a book. The article describes how low-cost, AI-empowered drone swarms could undermine the supremacy of the American military. While this technology does not yet exist, it is on the horizon and could allow nations like North Korea and Iran to dramatically increase their military capabilities at a fraction of the cost of traditional weapons. I want to read a book, either fiction or nonfiction, examining the potential of this threat, and, based on the insight he provided in the WSJ essay, Admiral Stavridis seems a good candidate to write it.

Perhaps the singularity, the merger of biology and technology, is a more imminent threat than I realize. Maybe we’re on the verge of a world where remote gene editing and other such tools will allow our enemies to kill or control our citizens and soldiers at will. Maybe, but I doubt it. For now, it is the realm of science fiction, and if I want to read about it, I’d rather leave it to those better skilled at telling those tales.

We should appreciate talented people like Admiral Stavridis, who dedicate a significant portion of their lives and careers to serving our nation, and we should listen when they share lessons learned from their military experiences. Rather than trying to compete with skilled science fiction writers, Admiral Stavridis should continue to address the dangers posed by evolving military technologies and emerging superpowers like China, as he did in his first book and the recent Wall Street Journal essay.