Nancy Bunge

On "The Minister's Black Veil"

From Nathaniel Hawthorne: A Study of the Short Fiction by Nancy Bunge (Boston: Twayne, 1993), 18-20.

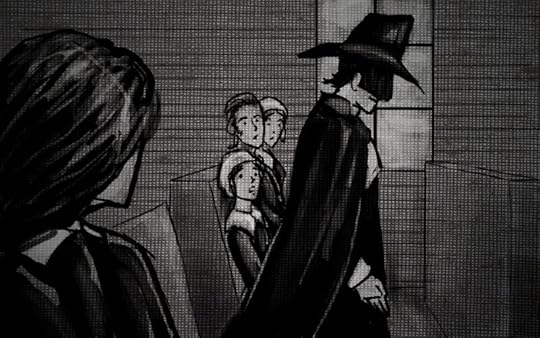

In "The Minister's Black Veil," the Reverend Mr. Hooper startles his congregation by appearing for Sunday services with a black piece of cloth over his face. He wears the veil for the rest of his life, refusing to remove it even on his deathbed. He protests he must display this symbol of his evil to serve as a moral example: "What, but the mystery which it obscurely typifies, has made this piece of crape so awful? When the friend shows his inmost heart to his friend; the lover to his best-beloved; when man does not vainly shrink from the eye of his Creator, loathsomely treasuring up the secret of his sin; then deem me a monster, for the symbol beneath which I have lived, and diel I look around me, and, lo! on every visage a Black Veil!"

Hooper's veil does educate. Others respond powerfully to him because it forces them to confront their depravity: "Each member of the congregation, the most innocent girl, and the man of hardened breast, felt as if the preacher had crept upon them, behind his awful veil, and discovered their hoarded iniquity of deed or thought... An unsought pathos came hand in hand with awe." While most attempt to evade this awareness, the dying realize they must face it and call for the Reverend Mr. Hooper. The veil also improves Hooper's funeral sermons: "It was a tender and heart-dissolving prayer, full of sorrow, yet so imbued with celestial hopes, that the music of a heavenly harp, swept by the fingers of the dead, seemed faintly to be heard among the saddest accents of the minister." And, it ties him to the dead; one parishioner claims it makes him "ghost-like," and at the end of his career, "he had one congregation in the church, and a more crowded one in the church-yard." Because of the veil's positive consequences, many critics believe the tale validates Hooper's behavior.

But Hooper's parishioners disagree. They no longer welcome the minister at weddings or Sunday dinner. They believe some occasions go more smoothly without a living parable of evil present. People sin, but they also experience joy and love. By turning himself into an unrelenting example of depravity, Hooper demonstrates a lack of generosity, most of all toward himself. His veil shuts out happiness, giving "a darkened aspect to all living and inanimate things." It may even distort his religious views, for it "threw its obscurity between him and the holy page, as he read the Scriptures." A number of critics embrace this view of Hooper. Nor surprisingly, a third critical contingent, the smallest, argues that Hooper, like most human beings, is both noble and foolish.

Hooper's fiancée, Elizabeth, sides with this group of commentators. When she threatens to leave Hooper if he does not remove the veil, he begs her not to abandon him: "Oh! you know not how lonely I am, and how frightened to be alone behind my black veil. Do not leave me in this miserable obscurity for ever!'" Indeed, it does isolate him: "Thus, from beneath the black veil, there rolled a cloud into the sunshine, an ambiguity of sin or sorrow, which enveloped the poor minister, so that love or sympathy could never reach him." But Elizabeth never leaves him. She sits at his deathbed, protecting the veil because it matters to him and because she loves him: "There was the nurse, no hired handmaiden of death, but one whose calm affection had endured thus long, in secrecy, in solitude, amid the chill of age, and would not perish, even at the dying hour." Love is there for Hooper, but the veil prevents him from seeing or enjoying it.