What do you think?

Rate this book

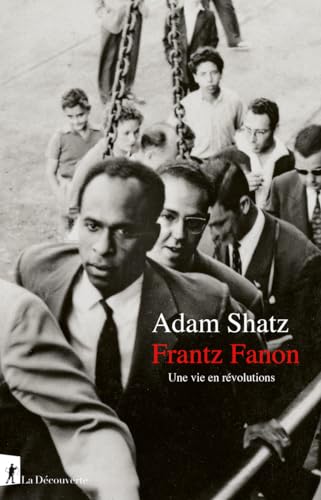

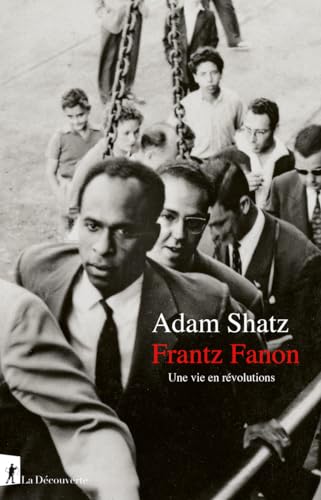

512 pages, Paperback

First published January 23, 2024

Fanon historicized the pathologies of colonial psychology by situating their formation in the structures of racial and economic domination, rather than in parent-child relations.

... if [Fanon] advocates the logic and necessity of counterviolence by the colonized, he is also explicit in his criticisms of a politics based on revenge: the revolutionary movement's obligation is to direct the violent impulses of the colonized toward pragmatic objectives, not to foment bloodletting or to treat all members of the settler community as legitimate targets.It is possible to find genuine quotes from Fanon which, when removed from their surrounding context, sound like someone saying: Go ahead, kill your oppressor, you’ll feel better, and you are perfectly justified. I hope you don't think that I'm trivializing the matter when I say that the misuse of Fanon in this manner reminds me of the recent misuse of the songs of Bruce Springsteen. The song “Born in the USA” is about the economic hardships of returning Vietnam veterans, but the people who are braying the title, over and over again, at the campaign rallies of Republican political candidates either don't know or don't care. The words “Born in the USA” are all they have to say about the matter. Similarly, you can quote Fanon accurately that, for example, “violence is a cleansing force”, but saying so doesn't mean you are acting in the spirit that he did, or understand his thought.