What do you think?

Rate this book

337 pages, Kindle Edition

First published September 4, 2012

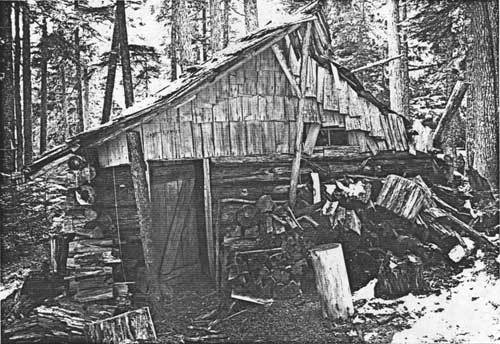

“He lived beside the sea in the far northwest corner of these United States, and in the nights before he left he sat before his tiny shack watching the ocean under the night blue sky. Sea grass sawed and rustled in a cool, salty wind. A few drops of rain fell upon his face, wetting his beard and softly sizzling in the fire. This light rain but the after-rain of the lasts nights storm, or perhaps the harbinger of harder rains yet to come. The shack creaked softy with the wind while the tide hissed all along the dark and rocky shore. The moon glowed full form amidst the rain clouds, casting a hard light that slid like grease atop the water. The old man watched ivory curlers far to sea rise and subside noiselessly. Within the bounds of his little cove stood sea stacks weirdly canted from wind and waves. Tide gnawed remnants of antediluvian islands and eroded coastal headlands, the tall stones stood monolithic and forbidding, hoarding the shadows and softly shining purple, ghost blue in the moon and ocean colored gloom. Grass and wind-twisted scrub pine stood from the stacks, and on the smaller, flatter, seaward stones lay seals like earthen daubs of paint upon the night’s darker canvas. From that wet dark across the bay came the occasional slap of a flipper upon the water that echoed into the round bowl of the cove, and the dog, as it always did, raised its scarred and shapeless ears.”

“Far to the west, where the night was fast upon the ocean’s rim, the clouds had blown back and the old man could see stars where they dazzled the water. He breathed and rocked before the fire. His thought, beyond his control, went from painful recollections of women and family to worse remembrance of war because it had been his experience that one often led to the other- stoking its fires until there was not a man who could resist and, upon yielding, survive as a man still whole.”

“Abel stood beside the fire and watched the ocean move constantly, restlessly, in the outer dark. He looked at the stars that glistened hard and cold through gaps in the clouds and at the hazy moon behind. He looked at the dog where it lay sleeping by the snapping fire. Older now, it tired easily and slept hard, its long legs moving restlessly as it gave soft little puppy-barks from its dreams. Abel watched it for a time, then shed his clothes and stood naked, pale and ghostly in the shadows.

He started across the wrecked driftwood toward the sand, picking his way along carefully. The tide seethed and rattled along the shore. It sprayed and echoed on the stones in the deeper waters and slapped against itself still farther out, under the moon as it moved beyond the clouds, where men could not dwell nor prosper. Beds of kelp, like inky stains upon the general darkness, bobbed on the swells while mounds of it, beached days past, lay quietly afester with night-becalmed sand fleas near the driftwood bulwarks. Glancing to the little river that cut sharply and dark through the sand, Abel saw the largest wolf he’d ever seen, standing in the current watching him.”

“His own grief was nothing but suffering, then passing through sorrow, rage. A black gall. Nights steeped in drink. Days of hungry wandering. Begging, petty thievery, and a single wretched night of a full moon passed out facedown in some churchyard’s grass. And when war did come, Abel Truman found himself in North Carolina with a regiment of Tar Heels for no other reason than that was where he had happened to be. And then all the rest happened, and finally, ten and twenty years in a one-room shack on the shore of the cold, grey Pacific, and his life was blown. Passed him by like a slow, tannic river easing out to sea. He’d eked out a meagre life beside the waters and when he felt he’d finally had enough he’d walked into the ocean and the ocean had cast him back.”

“A stillness now, as if the world were waiting, breathless. The wind did not blow and the day grew warm. They slept that night on the banks of some nameless stream for the cool of the water in the close, hot dark, and when they rose they could hear a distant, tearing sound as of a sturdy piece of canvas ripped lengthwise. It came banging intermittently through the springtime air all morning and in the afternoon the tearing became a roar and the roar was constant. They could hear shouting. They stopped on arise on the outskirts of a four-building village that lay abandoned. The Wilderness was before them, studded with powder smoke that rose, slow, malignant, until the sun was darkened and the shadows grew long.”

”“I was out front of my shack where I lived,” said Abel, choosing words carefully. “I like to sit and watch the ocean of an evening. The way the tide comes in and the different colors the sun puts on the water when it sets. At any rate, I remember standing up one day just as the last light was going out, and when I turned round it was shining back in the trees behind like there was fire in them. I seen fire in trees plenty of times, of course, but this was . . . But this was like how it was in the Wilderness, in the war. The light and the trees and I could suddenly . . . smell things I haven’t smelled in more’n thirty years. I had to up and practically pinch myself to be sure of where I really, truly was.” Abel sniffed and sighed. “It greatly disturbed me, as they say.”

“I was remembering how it had been when I realized how much I’d forgot. I don’t remember exactly what kind of trees there was back there. What kind of flowers there was. My wife, she planted us a little garden back behind our house when we was married, and I can’t, for the life of me, I can’t remember what it was she planted. Melons or corn or tomatoes or just a mess of flowers. A man ought to be able to remember something like that. And the color of her dress that day . . .” He faltered. “I can’t see it,” he said. “I can’t even see her face clear no more.”

“I just figured it was time for me to go on back home while I still can,””