What do you think?

Rate this book

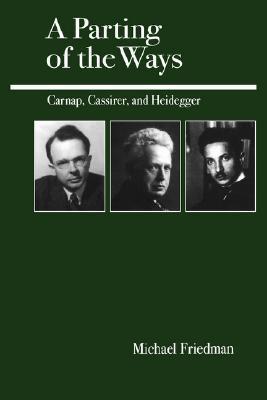

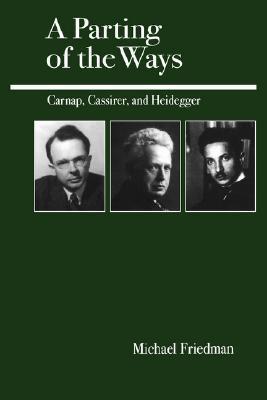

175 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2000

"In 'throwness' there is a being-delivered-up of Dasein to the world of a kind that such a being-in-the-world is overwhelmed by that to which it is delivered up.

Overpoweringness can only manifest itself as such in general for something that is being-delivered-up

In such being-directed-to the overpowering, Dasein is captivated by it and may therefore experience itself as belonging to and akin to this reality.

In thrownness, therefore, any being that is in any way revealed has the being-character of overpoweringness (mana)"