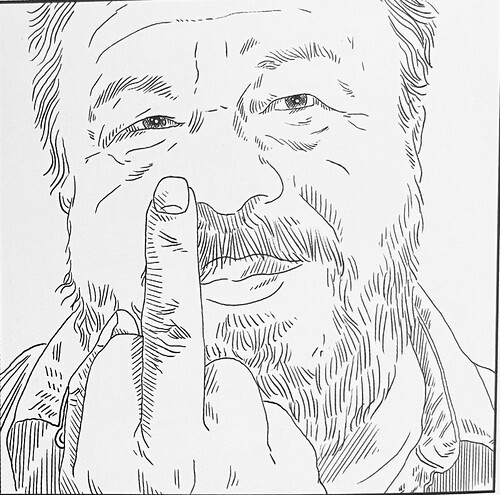

I haven’t done a review of a book in quite a while though I’ve been reading a lot. However, I couldn’t but hit the keyboard when I read the graphic novel Zodiac: A Graphic Memoir Al WeiWei. The cover is a rich gold but the insides are black and white with the narrative illustrated by the inimitable Italian comic artist Gianluca Constantini. The memoir is also a collaboration between WeiWei and Elettra Stamboulis, a comics author, curator, translator, and activist who has been involved in curatorial and creative practices developed with Gianluca Costantini for the Komikazen International Festival of Reality Comics (2005–2015). It is an explosive combination of artistic minds that is on view for the readers more so because of the intricate lines and hatching with which Constantini unravels and illustrates the tapestry of WeiWei’s life.

The book is woven using the 12 signs of the Chinese Zodiac - Mouse, Ox, Tiger, Rabbit, Dragon, Snake, Horse, Sheep, Monkey, Rooster, Dog, and Pig. WeiWei did not have much of a relationship with his father, a poet who joined the Chinese Communist Party but ended up persecuted and punished as a counter-revolutionary. The. story begins in China in the heat of Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution where reading anything other than what the Party determined as politically correct is dangerous. William Blake is banned, for instance, and Weiwei’s memory is of his poet-father telling him not to read. Cut to 2015 and WeiWei is telling his son about his life, and his views on the tangled web of relationships between art, time, folklore, symbols, ideas, and the reality of partaking of a shared humanity.

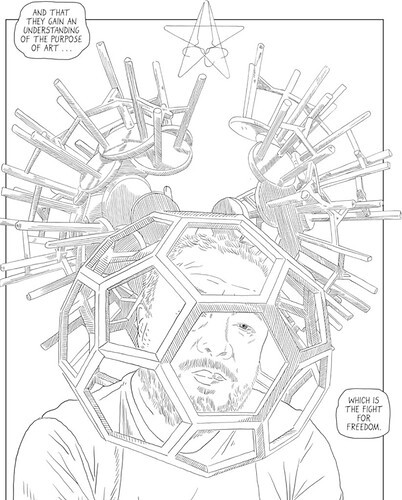

WeiWei’s son dares to ask questions being curious about everything but WeiWei is nuanced in his responses, even cautious. However, he passes on his acquired and accumulated wisdom to his son through storytelling and providing intricate exegeses of stories from Chinese folklore and the meaning of the Zodiac signs, relating these to the history of China and its politics, the necessity to survive socioeconomic calamities contrived by powerful rulers and to defend the right to freedom of expression which is under threat in a variety of forms and systems in different parts of the world. Art is the true mouthpiece of freedom of expression and art is the Cat that escaped being confined to the Zodiac.

I am a cat lover and so WeiWei’s understanding of the freedom of the Cat and how it came to be as explained by Chinese folklore left me struck by a lightning bolt right between the eyes. The sign of the power to forbid books is the sign of the Mouse and is the sign of betrayal. The Chinese Mouse is the proverbial Judas and represents every tyrannical, representative power that seeks to crush the rights of human beings to self-expression and dissent.

The story goes that Cat and Mouse were good friends. Neither could swim. The Jade Emperor invited all the animals to a race to determine which ones would be keepers of the year. They had to cross a river and Cat and Mouse climbed the back of Buffalo who agreed to help them cross. Mouse pushes Cat into the water and is first in the race.

“The Cat never arrived at the finish line but remained free” outside of the Zodiac system. The Cat is “an animal that can open doors but they are different from human beings because they never close the doors behind them.” The Mouse is the sign of war and politics and resorts to trickery to be first, it loves winning and maintaining the position of the top dog. The world is ruled by mice.

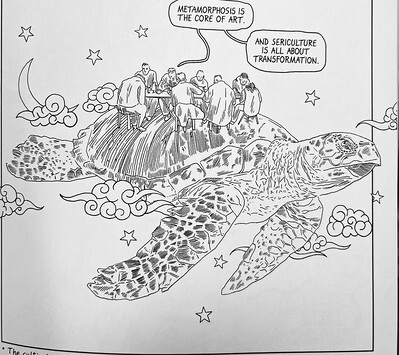

Each chapter in the book is related to a particular animal in the Chinese Zodiac and the book is a journey that takes one further out into the river of life and philosophy, beginning with waters that reach the ankles, then the knees, the hips, the chest, the face, and the artist is then carried along on its currents and life becomes equivalent to artistic musings, endeavors and fearless expression that opens the minds of those who encounter it and forces them to think and imagine alternate possibilities and realities. The artist is to be a mouse-catcher and mouse-killer and WeiWei realizes this as his forte. The mice trapper-killer is also a giant killer. “Like the cats, we have to keep the door that is called freedom of speech and thought open” when the mice come to close it through trickery, betrayal, show of force, threat of imprisonment, torture, surveillance, death, and exile.

In his memoir, WeiWei lauds writers and activists who paid a heavy price for standing up for art and their beliefs.

WeiWe mentions several artists and poets, Chinese and otherwise, like Liu Xiaobo, including Joseph Beuys and his famous performance with a dead hare/rabbit (representing immortality) and the planting of 7000 oaks to signify immortality through the magical idea of nature. WeiWei also speaks of some of his significant works like ‘Sunflower Seeds’, his installation of 1001 wooden chairs at Documenta 12, and Large, his installation at Alcatraz prison.

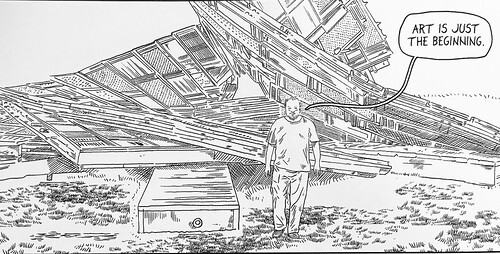

I am not going to describe more of this book which is multi-layered and will make you pause over each frame seriously and lovingly crafted by the graphic artist Constantini. The text is also weighed well and is, in a sense, sparse but evocative and fragrant, lingering in one’s senses like a time bomb that explodes at unexpected moments setting off cogitative or meditative tremors in one’s being. Through it all resounds and resonates WeiWei��s objective as an artist and storyteller: “What I was interested in was that an artist has to be the beginning of a story, not the end. We should ignite stories and let people meet.”

Well, I’ve read about WeiWei and seen his works second or third-hand, virtually, and remotely. But his memoir allows me to meet him across continents and time and space through text and image and I can carry his thoughts and aesthetic traces in me and let them form fresh rivulets that make me alive to art and magnify freedom of expression which particularly bursts forth when constrained, as the Oulipian writers and artists knew so well. (end)