What do you think?

Rate this book

221 pages, Kindle Edition

First published February 4, 2025

Suicidal ideation is the lightest, easiest thing in the world. It's an invisible hobby, a fun little secret you can take anywhere, like doing Kegels at brunch or doodling in lecture.

I've only recently come to see that my relationship to books has become, or perhaps has always been, an uncomfortable but necessary vacillation between love and terror—between bibliophilia and bibliophobia.

The book that would kill me and the book that might save me, sadness and reading, self-harm and writing, are the violent lifelong habits that made me who I am.

I was years away from understanding that there are certain books that modify your chemical composition so palpably you fear you might no longer breathe air or drink water.

My dad was scary and always unpredictable, but so are lots of parents. And lots of them are so much worse; we lived in a nauseating atmosphere of possible violence or near violence or mild violence, but as far as I know, it hardly ever erupted into physical danger, for me at least

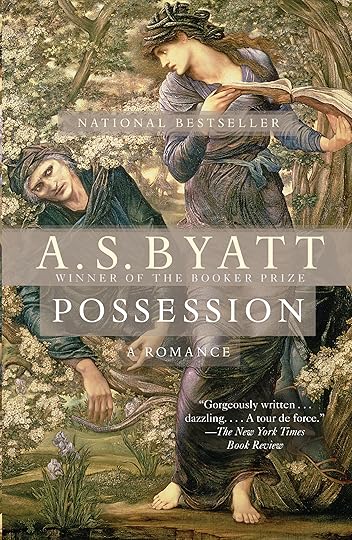

This time, it was not the kind of book I wanted to escape to, but rather, a book I couldn't escape from. It was unlike anything I'd read before—terrifying, unexpected, essential.

To call it a Life Ruiner is not to say that a life of letters is necessarily ruination—but rather, to identify it as the book you can't ever recover from, that you never stop thinking about, and that makes you desperate to reach that frightening depth of experience with other books.

...a book also won't betray you. It is the only truly secret love affair you can have; the book will never tell what you show it, even as you reveal your truest self to the page.

I was going through a breakup, and "The Glass Essay" is indisputably the greatest breakup poem ever written. (Don't try to argue with me on this.)

I peered into Carson to see myself, as she peered into Brontë in turn—a nested series of readings and rereadings in the search for newer, deeper meanings.

Imagine the book that solves all your problems. It knows where you come from and where you hope you're going. It reads you as you read it.

I have always carried a passive guilt about being Japanese in America rather than Japanese American. [...] I often have the nagging feeling that I don't have a right to belong to an Asian American community.

The great cruelty of writing is this realization that the experience for which I long the most as a reader—an encounter with someone who makes me believe that they have articulated exactly my thoughts, exactly my feelings, in the most perfect and irreplaceable terms—is a kind of death.

Is this simply what I'm doing here, in this book, trying to burnish my writerly credentials with this proof that I've been through something real? Am I a fool to think that I'm far away enough from it to write about it—am I still not past it, but in it?

There is no guarantee that it will not happen; I cannot in good conscience tell you that I have totally let go of either the suicide plot or the reading-for-salvation plot—for what is this book if not a version of that?

“I was enraptured by the book itself but equally enraptured with the sense that it gave me someone to be.”

“I immediately, repeatedly reread certain passages at a word-by-word crawl, not to understand what happened, but to figure out how it was happening…”

“We indeed are all ‘by-products of the mid-twentieth century,’ as Ozeki writes, and I irrationally and grandiosely fear that like microplastics, like neo-imperial structures of power, like the internet, I too am circulating some insidious unknown poison as I move through the world.”

“To call it a Life Ruiner is not to say that a life of letters is necessarily ruination–but rather, to identify it as the book you can’t ever recover from, that you never stop thinking about, and that makes you desperate to reach that frightening depth of experience with other books.”

“How important it is to read a book that so undoes you that it becomes a precious token of your own destruction to carry to the end of your days.”

“That’s the annoying fact that challenges all writing about depression: It is just not a good story. It usually does not have a clearly defined beginning or ending; it’s mostly just terrible, boring middle after terrible, boring middle.”

“It is more than the dull throb–it is a dull dullness, a drained immobility that I would not have had words to explain then, as a child of seven or eight, except to say ‘I’m tired.’”

“...living as I have among books, I have been cultivating the feeling of being a ghost for a long time.”

“I alternated between being someone who was forever at the mercy of plots I had no control over, and being someone who believed they knew exactly how those plots worked: in other words, between being a character and being a critic.”

“When the time came, and I asked for help, nobody was more shocked than I. It was like I’d turned to the end of a book I’d read a hundred times and found that somehow the words had changed–or rather, that I myself had unwittingly rewritten them.”

“Nervous breakdown was not for the children of immigrants.”

“I still feel it involuntarily in my body now. My fingers, resting on the keyboard, are suddenly cold. A chill thread tugs upward through my spine, snagging and gathering nerves as it goes. There is a slight, irregular flutter somewhere deep inside my chest. The curved outer rims of my ears ache weirdly like someone is pulling up on them.”

It is undeniably ludicrous that my suicide note was going to be a meticulous cat-care manual, but also so purely practical it scares me; it's so terribly matter-of-fact. It did not seem silly to me at all at the time.

The alarming sensation that I've been trying to describe, of haunting a text or letting it haunt me, is not about inhabiting a character. Instead, I experience these moments of getting pulled into a text as a frightening total convergence between my self—whatever immaterial thing that is—and the text as a whole.In a typical reading, Chihaya's conversational approach, especially in the Ozeki portion, would've pissed me off something first. But by the time I was registering some of the worst exigencies of the tone and style, I was already in full thrall to the analytical rhythm, particularly potent when the read wasn't all that difficult and the length all the more reasonable. Even The Bluest Eye was another strike of the bowling pins, if from the refracted viewpoint that acknowledges one's self was and never will be the intended target of such incisive devastation. For all that, I am still grateful that I had developed sufficient critical reflexiveness to review the work in the way I did, if only to add my little toothpick to the tools chipping away at the death cult that is the white aesthetic.

It was only in the last few years that I have realized, largely after being reprimanded gently by friends and therapists, that these might be stressful stories to other people. They're still funny to me, though, because they have to be.For all my praise, it's still unmooring to lack back on this reading experience and not feel the slightest bit of real equivocation insisting upon itself. Bias, of course, with habitus, breeding, plus the length that satisfied without sludging, a type face that mobilized without flitting, and a sense of a generation that may have tracked onto Anne with an E on one side of the globe and Sabriel on the other, but was a reckoning with books and the self-isolating, maladaptive day dreaming, life sustaining deal with the nearsighted devil in our time of late capitalism. I still find Chihaya's formal definition of 'bibliophbia' about as useful as Eco's 'antilibrary' when it comes to my own readerly relationships (smacks too much of the closest homophobe stereotype for my liking), but for all that, this book did more to clarify my own bibliosthetics of the last twenty years than a decade of degree obtaining + professional work in librarianship has so far won me. It's certainly not going to do it for most, but for those of us still stuck on the Plath and the Sexton and the Woolf, stop. Let go. Come a little closer, out of the rain and into the cabin. Live a little in the world of smartphones and Tiktok. It won't kill you: I promise.

INTERVIEWER: Isn't a writer meant to have a sliver of ice in their heart?P.S. If I had to pick a Life Ruiner, it would have to be To the Lighthouse, the book that convinced me to drop out of college. And if for some freak reason I had to pick a backup, it would have to be Infinite Jest, the first to truly show me the water.

NUNEZ: Yes, but not for the reader.

-SIGRID NUNEZ, "The Art of Fiction no.254," The Paris Review