Not quite like anything I've ever read before, and I'm not sure what to make of it, or whether or not to say I "liked" it. Something like 3 stars for enjoyment, bumped up to four for novelty and for my curiosity about where this is all going. In any case, I'll definitely be continuing to the second volume (of five).

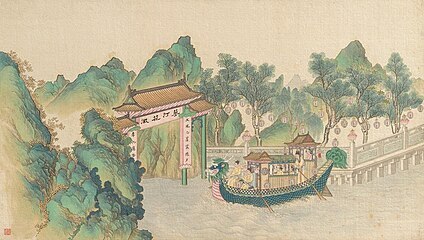

The Story of the Stone, more commonly (I think?) known as The Dream of the Red Chamber, is one of the "four great classical novels" of Chinese literature, and often said to be the greatest of the four. Sometime last year I become curious about Chinese literature, about which I knew nothing at all, and figured this would be as good a place to start as any.

I feel a bit hesitant about focusing in this review on how unusual this novel is to someone not familiar with Chinese literature. I don't want to overstate its distance from "Western literature" -- which after all is a giant category that includes many disparate and odd things -- or present it merely as some sort of exotic curiosity to be gawked at rather than a work to be judged on its merits like any other. However, having read only a small part of the whole work at this point, I don't really feel qualified to judge it or even say much about its artistic qualities at all. All I have are some preliminary impressions that amount to, "well, that was different." So here we go.

The two main things that struck me as "odd" or "different" about this book were the tone and the narrative structure. The tone is a mixture I haven't encountered before. On the one hand, much of the story is lighthearted and whimsical in a way that reminds me of nothing more than Western children's literature. This feeling is bolstered by the fact that the central characters are young adolescents, and that the protagonist, Bao-Yu, is cosmically "special" (being the incarnation of a magic piece of jade) in the way many children's fantasy protagonists are. The young characters are depicted as realistically childish, and there is a great deal of teasing, awkward juvenile flirtation, and the like, none of which would be out of place in, say, one of the earlier Harry Potter books.

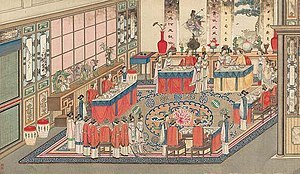

However, the story as a whole is emphatically not a "children's story" -- there are intermittent bursts of shocking violence, morbid cruelty, explicit sexuality (among the older characters), and so forth. As well, the childish antics take place within a large aristocratic clan and a great number of pages are given over to the day-to-day business, minor power struggles, and the like that take place among the older family members and among the numerous servants.

So if I could try to describe the overall "feel" of the book by comparison to Western literature, the closest thing I could come up with is something like "a cross between one of the first few Harry Potter books and some 19th-century chronicle of an aristocratic family, with recurring flashes of gothic horror and metafiction." Though even that isn't really very accurate.

As for the structure, it's highly episodic and lacks a "through-line" of narrative tension. Highly tense or dangerous situations arise quite suddenly from time to time, but are typically resolved within the same chapter that introduces them (or, if not, in the following chapter), and tend to make few obvious marks on the story as a whole. Many chapters have nearly no tension and simply recount some episode of minor clan politics (among the adult or servant characters) or juvenile antics (among the child characters). Most of this is pleasant, in a low-key way, but creates little feeling that the story is "going somewhere" or building progressively, which is odd in conjunction with the portentous way it begins (Bao-Yu is incarnated from a magic piece of jade, and one expects his life to be somehow special or unique in consequence).

Much as it contains many discrete episodes whose significance to the whole is not always made clear to the reader, the book also contains a very large number of characters (hundreds, I think), and it makes little effort to indicate directly which of these characters are most central or important. As a result, it was quite difficult to get my bearings in the early chapters, as I was confronted with a flurry of names, some of which recurred from chapter to chapter and some of which didn't. (Of course it was harder to keep track of the characters because I'm not used to Chinese names; what's more, many of the characters are related and have the same family names. Thankfully, this edition has an appendix of characters.) After a while, it became clear that certain people were major characters and I began to recognize them as distinct entities, but it took a few hundred pages for me to really feel comfortable, and even after 500 pages I still resigned myself to thinking "who's (s)he? oh well, probably doesn't matter" pretty frequently.

The characterization even of the main characters takes place in this distinctive atmosphere, one in which scores of people continually disappear and reappear from view and the reader is expected to cheerfully keep track of it all as though every one were a dear friend. The relationships between Bao-Yu and various other characters, for instance, are rarely "introduced" to the reader in a distinct way, but instead become gradually apparent as one watches him interact with people he has already formed pre-existing ties to. There is a constant feeling of coming into something complicated in medias res and trying to get a sense of it without clear signposts.

The back cover of my edition, for instance, informs me that the story centers around a sort of love triangle between Bao-Yu and two other characters, Dai-Yu and Bao-Chai. But this is not introduced to the reader in a set of clear-cut dramatic set-pieces; instead these three characters appear incidentally in various episodes, sometimes individually, sometimes apart, and if their relations to one another are especially important, it is left for the reader to "pick up" on this signal coursing through a much larger sea of (realistically?) profuse details. It wasn't until the last third of this volume, for instance, that I had any sense of Dai-Yu's personality -- Dai-Yu being, like all the other characters, a figure who pops up from time to time rather than a player in some consistent, progressively developed dramatic narrative -- and Bao-Chai is still largely a mystery to me (I hope and expect she will be more thoroughly characterized in later volumes).

Much of what I've said may just reflect the fact that I have only read a small part of a larger whole. It's possible, for instance, that the "dramatic through-line" I found lacking simply hasn't developed yet. But it nonetheless seems significant that such a through-line hasn't emerged in 500 pages of incident. All in all, I'm not sure how I feel about this style of storytelling, or about the book as a whole, and am hesitant to say any more until I've read further. But my curiosity is piqued, though I'm not sure how much of that is due to Xueqin's skill and how much of it is due to the simple novelty of such an unfamiliar literary form.

(As always with translations, I also wonder what I'm missing by not reading it in the original. David Hawkes' translation is apparently well thought of, and it reads pleasantly and maintains a impish, whimsical tone [which I imagine is consistent with the original?], but it's rarely excellent, as opposed to merely serviceable, by the standards of English prose.)