“The nineteenth century reduce[d] Elisabeth and Eugénie, two of the most layered women of their time, to attractive footnotes on the pages of history. This age belongs instead to Victoria, its most enduring female monarch…But it is a mistake to overlook her sister sovereigns in France and Austria. Fearless, adventurous, and athletic; defiantly, even fiercely independent, Sisi and Eugénie represented, each in her own way, a new kind of empress, one who rebelled against traditional expectations and restrictions. Their beauty was undeniable but so too was their influence on a world that was fast becoming recognizably modern. As railroads for the first time crisscrossed kingdoms, and telegraphs linked continents, their lives would become so entwined that it is impossible to understand one without the other, or indeed the whole glorious whirlwind of a century in which they lived, without the beguiling power of their stories…”

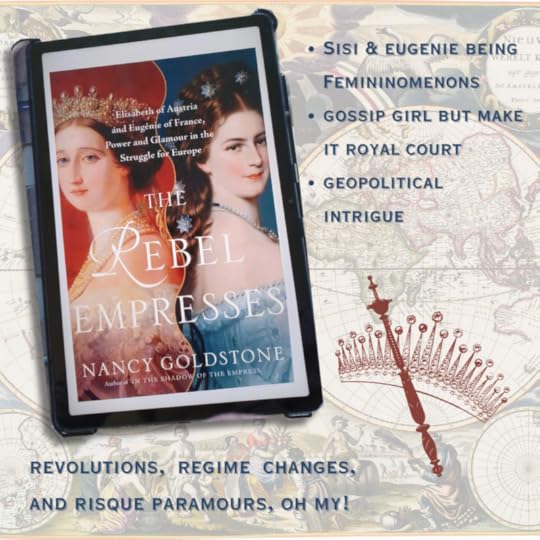

- Nancy Goldstone, The Rebel Empresses: Elisabeth of Austria and Eugénie of France, Power and Glamor in the Struggle for Europe

Historical reality is incredibly grim. If you journey along the timeline of our existence, you will find it full of unfun things: wars and genocides; famines and disease; slavery and exploitation; corruption and pollution. As Kurt Vonnegut astutely noted: “All great literature is all about what a bummer it is to be a human being.”

On the other hand, the study of history is entertaining. I mean it! At the risk of sounding like a psychopath, all the ugly realities above make for compelling drama in the pages of a book. While obviously unpleasant, the past is also gripping, profound, and occasionally inspiring, especially when one centers it on people, rather than theories.

Nancy Goldstone is an author who understands this. She has forged a successful career highlighting or reframing some of the great women of the world, who have either been misinterpreted or outright ignored. She continues that in The Rebel Empresses, a dual biography of Empress Elisabeth (“Sisi”) of Austria and Empress Eugénie of France. Like her other works, this one is thrilling and fast paced, addictively readable, novelistic in detail, and intimate in focus.

My only problem – which is a compliment, in a way – is that both Sisi and Eugénie deserve their own books.

***

Perhaps a quick introduction is necessary, as neither Sisi nor Eugénie have quite the same name recognition – at least in the United States – as Queen Victoria or Catherine the Great (though fans of Netflix’s international slate will recognize Sisi from The Empress).

Sisi married Franz Joseph of Austria, the man who – after her death – ultimately made several fateful decisions ensuring the outbreak of the First World War. She was incredibly beautiful, a fact that shines through despite her subdued black-and-white photos. She also happened to be incredibly compassionate, adding an important dimension to the otherwise stilted court of the Hapsburgs.

Meanwhile, Eugénie – more ambitious than Sisi – intwined her destiny with that of Charles-Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, the self-styled Napoleon III, who overthrew France’s Second Republic and created the Second Empire.

Both women held their titles during the tumultuous years in which the old empires of Europe began edging toward their own destruction. In other words: they lived in interesting times.

***

The lives of Sisi and Eugénie only rarely intersected, though Goldstone makes the most of these meetings. As such, The Rebel Empresses is essentially two different books, each a chronological narrative that – at regular intervals – switches between each woman. The segues are clearly demarcated, and there is little chance for confusion, even if Goldstone sometimes has to jump back and forth in time.

Despite being contemporaries, I am not wholly convinced – though Goldstone clearly is – that the lives of Sisi and Eugénie really informed each other all that much. Instead, their biggest similarity is that they occupied the same job in the same period of time.

***

At 558 pages of text, The Rebel Empresses pushes the page-count limits for a volume of pop-history. With that said, it is about 558 pages short of what is required to fully comprehend the lives of Sisi and Eugénie. The result is a breakneck recounting that is thoroughly fun to read, and that is brimming with incident, but is not as rich or comprehensive as it could have been.

To take one example, Goldstone ends her work with Sisi’s death, covering the final twenty years of Eugénie’s life in one page. This is a letdown, for having known her in her youth, I wanted to spend time with her as she aged.

***

With a heavy emphasis on their early lives, Goldstone describes how both protagonists were born into relatively privileged circumstances, and eventually came to embody a certain aristocratic style that is still fetishized today. For all their superficial similarities, however, they were quite different in important ways.

Sisi came from Bavarian nobility; enjoyed a free-flowing upbringing; and was athletic, thrill-seeking, and a romantic. Essentially stealing Franz Joseph from her sister, she married out of love, and soon came to discover that in royal marriages, love did not make the list of priorities. Hemmed in by the protocols of court, and hounded by Archduchess Sophia, her hellish mother-in-law, Sisi chafed in her role, often leaving Vienna for length, semi-controversial excursions elsewhere.

On the other hand, Eugénie came from a family of strivers, and actively maneuvered Napoleon III into marriage. Unlike Sisi, she played a more active role in governance, and served as regent for a time. She valued the power that Sisi abjured.

Quite a bit happened while these two women wore their crowns. A short list of events they lived through include the Revolutions of 1848, the Crimean War, the saga of Archduke Maximillian in Mexico, the Austro-Prussian War, the Franco-Prussian War, and the Paris Commune. Goldstone does a decent job of sketching this context, but given the premium of space, it is necessarily cursory. The secondary cast – the aforementioned Sophia and Maximillian, Carlotta of Belgium, Otto von Bismarck – is absurdly deep, and I would’ve loved more time developing their characters.

Rather than fully placing these women in their times, Goldstone focuses on their personal experiences. The very notion of monarchy and royalty is an ongoing con-job to which many willingly submit. Like so many other institutions, it is simply a mechanism for gathering wealth and power to the few, and forcing the many to grovel for what remains. Even with their fantastic wealth and benefits, though, it’s unlikely that many would have exchanged places with Eugénie and Sisi. Eugénie was constantly humiliated by a cheating spouse; had to flee from France, after that cheating spouse tried to match wits with Bismark (an encounter akin to bringing a croissant to a gunfight); and lost her beloved only child during the Anglo-Zulu War. Sisi endured ritual indignities at court; lost one child to sickness; and lost a second child – the heir to the throne – to a weird murder-suicide at the Mayerling hunting lodge. To cap it all off, she also lost her life to an anarchist assassin.

Heavy lies the crown, as they say.

***

Given Goldstone’s reputation, as well as the source notes included in the book, The Rebel Empresses is the result of serious research and thought. Yet it is not written in the self-serious, leaden manner of many academic treatises. Goldstone employs a brisk, often tongue-in-cheek prose style, filled with asides, tangential footnotes, and the occasional commentary on the patriarchy.

In short, this is an effortless read. This is not to everyone’s tastes, of course. For my part, I’m firmly in the camp that sleuthing dusty libraries and documenting primary sources is only part of the historian’s discipline. It also requires storytelling prowess, which Goldstone has in abundance.

Ultimately, I’m reading this during the limited free time I have in a limited lifespan. I’m not looking for another chore.

***

The Rebel Empresses is not Goldstone’s first crack at a multi-person biography. It seems to be the structure with which she is most comfortable. Far be it from me to criticize her for that. At the same time, it is not as though we have too many books about the role of women in history, and it seems something of a shame to cram two fantastic lives into one.

Sisi and Eugénie never ruled in their own right. They did not lend their names to an age. They did not make the critical decisions so beloved by proponents of the “great man” theory of history. But this does not make them any less worthy of study or remembrance. Married to a couple of fail-crowns who drove their respective empires into the ground, Sisi and Eugénie managed to carve out roles for themselves by pushing at the bounds of convention, utilizing their wit and acuity, and precisely wielding the gifts granted to them by nature.