What do you think?

Rate this book

160 pages, 15 x 17cm

First published January 1, 1966

he sat there before the open window as if before a curtain with these two hills in front of his nose sagging at the middle like the mattress on his bed with this sky like the old rug in front of the stove round like the trees in front of him out there or in there with this branch like the glowing stovepipe at this position of the sun this landscape like a box with the outside painted on the inside the doors open the shutters warmly heated this room in the hotel is it winter?Time progresses, sometimes in a linear fashion, but most definitely not always—it is hard to tell due to immersion in a dreamlike logic, where disorientation passes for normal to the point where total surrender is the only way to experience the prose.

even as a child goldenberg had had a morbid yearning for perfection. today the photo transparency was somewhat faded at the edges, but had descended distinctly enough over his perceptual apparatus, a guillotine had put an end to his powers of perception, and the stream of his consciousness flowed electrically through now-porous walls of deduction, trickling into channels where once smooth isolators had continued to dictate simple routes.It would seem that even while Bayer is describing the life and times of a group of friends, he is also digging deep into goldenberg’s psyche, rotating between the external and the internal seemingly at random, as day continues to turn into night and some form of life moves on.

the night pales, ulcers—gray at first—burgeon in from the dark on all sides, assume colour, become distinct, turn into houses, the city, his friends, the tram that will drive him away. someone places some money in his hand and he and his apparition disappear. a butcher takes goldenberg’s place in space and moves about in his stead, dragging along blood-stained baskets.Throughout the book characters announce they have ‘the sixth sense’—the perception of a transcendent state beyond linear time and fixed identity. It is a recurring question of who has it (and what has it—at one point goldenberg wonders if bats do) but also of the veracity of these claims. What does seem to be the case is that ‘the sixth sense’ might be wished for but does not appear to be attainable through willpower—it arrives (and departs) without warning. Once granted it seems to offer a way to leave behind the paradox of how the awareness of our existence and the passage of time does little to help us grapple with the meaning of life and our place in the world.

what is left of me? a sound of flowing water. obviously i know that it’s night and presumably my body’s lying there somewhere. but what does that help?The questions never resolve themselves in this book, as it should be. Likewise, there is no change over time to Bayer’s tacit acknowledgment of the lingual inability to properly parse the questions. And yet throughout his modest literary output, Bayer didn’t permit these limitations to stop him from still stretching the elasticity of language in his inquiries. With his own specialized tools he approached fundamental questions of philosophy, and the literary works his efforts yielded were often strange, yet irrigated by that familiar dark stream running underneath us all.

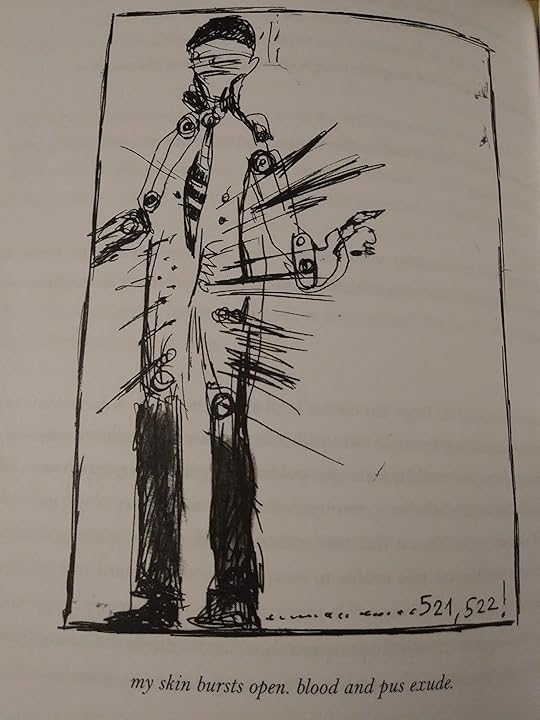

time is a solid body in which we move, goldenberg had known when he was still alive.One of the drawings made by Günter Brus for this edition:

or is it an allegory of ourselves that we gradually become aware of? dobyhal pondered.

Time? said Goldenberg... it is just a cutting up of the whole, by means of the senses.

We cannot penetrate the world, we have nothing to do with it, we create images of it that suit us, we establish methods by which to act in it and call it the world, or when things go wrong, me in the world, it is more than a little arrogant when we demand a painted backdrop which allows us to name and be tragic about our gestures and personal wishes which we normally designate as things, connections and the like.

suddenly large guinea-pigs appear on all sides.That’s not a metaphor in the text.

the perspective is a really perfidious trap!But that idea – of what we can manage to bear – is important. Those with the sixth sense are burned up from the inside, skin and eyes cracking, fevers reaching 120 degrees. Now, mind you, in the context of the book this doesn’t stop them from continuing to participate in the narrative, but the occurrence is important nevertheless.

“so if we had other lens in our eyeholes so that everything was distorted and when we raised our gazes the church spires shot up and when we dropped our gazes our feet went flying away and we could grasp the things and say this thing is exactly so long and would take the distance we had grasped hold of for this image than everything would be in order.”

“precisely” replied goldenberg, “we take in things just like that and just the amount we can manage to bear.”