What do you think?

Rate this book

416 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1995

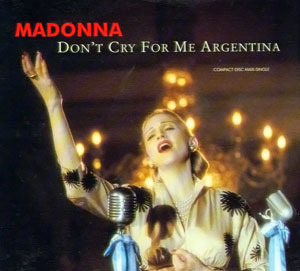

The movie answered many of the questions that I had regarding Evita Peron. The movie came out 10 years after President Marcos left the Malacanang Palace during the 1986 People Power revolution but the memories of her wife, Imelda Marcos, were still fresh in people's minds. Somehow, comparisons to these two ladies came so easily that a similar stage play, Meldita was also staged and later an independent film, Imelda was also shown.

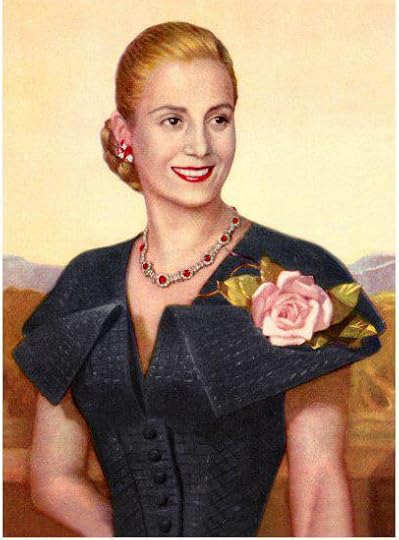

The picture taken when she was the First Lady of Argentina in 1945 at the age of 23.

"As you said, it's a novel," I explained. "In novels, what is true is also false. Authors rebuild at night the same myths they've destroyed in the morning."

"Those are just words," Corominas said emphatically. "They don't convince me. The only thing that means anything are facts, and a novel, after all, is a fact."

That, I thought, is where written language falls short. It can bring back to life feelings, lost time, chance circumstances that link one fact to another, but it can't bring reality back to life. I didn't yet know—and it would take longer still for me to feel it—that reality doesn't come back to life: it is born in a different way, it is transfigured, it reinvents itself in novels. I didn't know that the syntax or the tones of voice of the characters return with a different air about them and that, as they pass through the sieves of written language, they become something else.

The marriage is not false, but almost everything the document says is, from beginning to end. At the most solemn and historical moment of their lives, the contracting parties, as the phrase was in those days, decided to perpetrate an Olympian hoax on history. Perón lied about the place where the ceremony was performed and about his civil status; Evita lied about her age, her place of residence, the city she had been born in. Their statements were obviously false, but twenty years went by before anyone questioned them. In 1974, in his book Perón, the Man of Destiny, the biographer Enrique Pavón Pereyra nonetheless declared that they were true. [...] They lied because they had decided that, from that moment on, reality would be what they wanted it to be. They did the same thing novelists do.

Without Perón's terror, Borges's labyrinths and mirrors would lose a substantial part of their meaning. Without Perón, Borges's writing would lack provocations, refined techniques of indirection, perverse metaphors.

He refused to concede the fact. Although I have read little Borges, he said [or rather lied], I have some memory of that story. I know that it is influenced by the Kabbala and by Hasidic traditions. To the Colonel, the slightest allusion to anything Jewish would have been unacceptable. His plan was inspired by Paracelsus, who is Luther's counterpart, and at the same time the most Aryan of Germans. The other difference, he said to me, is more important. Detective Lönnrott's ingenious game in "Death and the Compass" is a deadly one, but it takes place only within a text. What the Colonel was plotting was to happen, however, outside of literature, in a real city through which an overwhelmingly real body was to be transported.