What do you think?

Rate this book

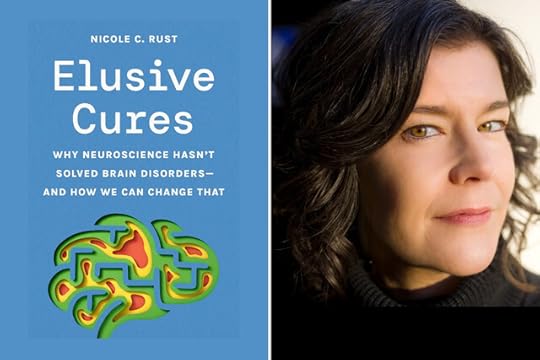

296 pages, Hardcover

Published June 10, 2025

"..I acknowledge that there are complexities around whether and when we should consider some conditions as “dysfunction” as opposed to a type of neurodiversity that society has wrongly become intolerant to—cases of autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and depression are all examples. That said, for each of these conditions, a subset of diagnosed individuals suffer in ways that can benefit from treatment. For those individuals, when our existing treatments fall short, we need better ways to help them. With this empathetic spirit, I use the terms “dysfunction” and “disorder” to refer to the conditions of individuals who need better solutions than the ones we can offer them today."

"I am a neuroscientist, and I have been engaged in brain research for over two decades. For a long time, I’ve been convinced that I have the best of all possible jobs: I get paid to think up new questions about how the brain works and answer them. A large part of what inspires my research is my intense curiosity about how the brain gives rise to the mind, and to ourselves. To answer these questions, I focus on memory. I investigate questions like: When we have the experience of remembering that we’ve seen something before, what is happening in our brains? How do our brains manage to remember so much? And how do our brains curate what we remember and forget?

My work is not driven just by curiosity; I believe that a foundational understanding of how memory works will contribute to future treatments and cures for memory dysfunction, including age-related dementias such as Alzheimer’s. In fact, part of my research program focuses on transforming what we’ve learned about memory into the earliest stages of developing a new treatment for memory impairment. Ours is but one example of what is known as the bench to bedside approach, where fundamental research discoveries are the first step toward developing new clinical treatments."

"Hands down, the most profound and important insight I’ve had while writing this book is that the end goal of treating brain dysfunction amounts to one of the most formidable of all possible challenges: controlling a complex system. Not in the creepy or cartoonish sense of “mind control,” but in the sense that treatments require shifting the brain from an unhealthy to a healthier state. This challenge is so formidable that there are questions about whether it can even be done in principle (much less in practice). The answer depends on exactly what type of complex system we’re dealing with.

To illustrate, let’s look at what happened when we tried to control another complex system: the weather. Today, we don’t try to influence the paths of hurricanes. Why not? It’s not because we haven’t tried. Often forgotten about the history of weather research is that we did try, only to realize that it probably won’t work. Thus, we need to ask ourselves: What makes us think that the brain will be any different? After all, an epileptic seizure or psychosis might be likened to a tornado or a hurricane insofar as it’s a complex system gone awry. Under what conditions can we effectively control a complex system?"

Enough to think there are upsides to incorporating the use of AI in how we solve problems in our organizational/work systems, the reason being that AI can scan everything the internet knows and can automate simple processes currently performed manually (with human frustration). In order to move an organization forward, human problem-solvers need to be free and focused, to be able to ponder and explore ideas, to brainstorm with AI as an initial sounding board, and then to refine options or possibilities unfettered by the typical traps endemic to the creative process.