Listen, you young lads, listen to our tales.

We old folks, we have much to tell.

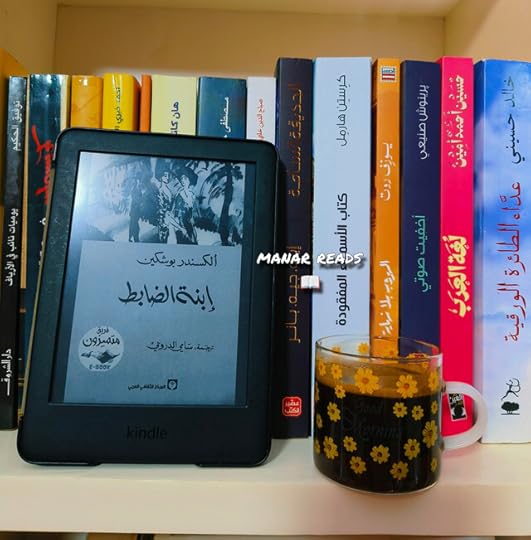

Pushkin was still in his thirties when he published this short novel, but wise beyond his age. I do wonder what amazing stories were cut short by the bullet that ended his life prematurely only a few months after the publishing of this historical romance. Pushkin had style, he had vision, a subtle sense of humour and a keen social engagement. No wonder the whole Russian literary school pays homage to the master.

As far as I’m concerned, I couldn’t be bothered with required books while in school, preferring adventure travelogues, pulp crime and science-fiction at the time. In a way, this worked for the best, because I am better able now to put this novel in the context of its period: a reaction to the romanticism of Walter Scott, Victor Hugo and Lord Byron, tempered by modern sensibilities, by robust oral traditions in storytelling and by a sharp satirical pen worthy of Lawrence Sterne or Daniel Defoe.

Mama was still pregnant with me when I was enrolled as sergeant in the Semyonovsky Regiment through a close relative who was a serving major with the Guards. If my mother had given birth to a daughter – Heaven forfend! – Father would have immediately reported the death of an absentee Guards sergeant, and that would have put an end to the matter.

Pyotr Grinyov has his journey all mapped out from before he is even born. Noblesse oblige for the Imperial Russia francophone aristocracy, and the young man receives all the gifts of his class – a personal servant, a French tutor (albeit a drunk and womanizer scoundrel] and a lot of freedom to roam around the estate doing whatever took his fancy.

Worried that his son will develop into an effete courtier, the father decides to send him to the army, only instead of the designated position in the Imperial Guards, young Pyotr is dispatched to the recently pacified southern border, to a remote fortress named Belogorsk.

True to his nature, the young man starts by getting drunk and gambling away a fortune in one night of debauchery in the company of an older officer. Yet, there is some basic honest core to his soul, displayed in his acts of contrition towards his serf and in his generosity towards a stranger met during a blizzard. Both of these acts will be important in the later economy of the novel, but before that, Pyotr arrives in the middle of nowhere and reports for duty at Fort Belogorsk.

Hear me, hear me, captain’s daughter.

Stay indoors at night. You oughta.

The place has very little to recommend it: just a few impoverished hovels, some morose conscript soldiers and a lot of shady Cossacks riding around the palisades. Yet the commander of the fort has a beautiful young daughter [and a rather bossy wife], so the young officer settles down to write love poetry to his muse, to eventually fight a duel for her honour against a fellow officer and to worry his parents with an importune request to bless his engagement to the poor girl.

History puts a hard stop to the budding romance, since this is the year 1773 and the Pugachov rebels come to visit Fort Belogorsk. The young Pyotr is one of the few surviving officers of the ensuing massacre when Pugachov recognizes him as the noble who has helped him in his hour of need.

We are treated now to a full account of the Pugachov campaigns in the Orenburg province and elsewhere in Russia, inter twinned with the efforts of Pyotr to rescue his beloved from the hands of a traitorous officer.

I find it remarkable how Pushkin, with his pen trained from epic poems to be concise and efficient, can dispatch in a couple of dozen pages what a modern fantasy or historical writer will bloat into a couple of serialized volumes. I still feel like a have a clear picture of both sides in the conflict, the class-conscious Russian aristocracy and the bloody-minded yet party prone Cossacks., from this very short novel.

Pugachov will eventually be brought down, but for Pyotr and the captain’s daughter the road ahead remains deadly perilous until the issue is taken to the Great Catherine herself.

>>><<<>>><<<

Pushkin Press celebrates its Puskin publication with the addition of two of his best short stories, further proof of his talent, if any was needed after the end of the main attraction.

The Stationmaster is a typival Gogolian tale, only it was published in the same year [1831] with the first ‘Ukrainian Stories’ from Gogol. The similarities include the country setting, the narrative device of the visitor who witnesses the events, the look at the administrative bureaucracy and the bittersweet nostalgia for the little man who passes away ignored by the high society.

The place is a horse exchange post for the mail service, also used by government officials. The unsung hero is the man in charge of the station, an ingrate job that many find fault with and are quick to criticize. This man has a beautiful daughter that turns the head of many a passing officer, until one day she runs away with one of the more dashing type, breaking the heart of her father into the bargain.

When all’s said and done, what would become of us if, instead of the accepted rule, rank before all , a new one was introduced – say intelligence before all? Think of the arguments that would arise! And how would servants know whom to serve first? But, back to the story.

>>><<<>>><<<

The Queen of Spades also reminds me of Gogol, in his Gothic supernatural period, but it may very well be the source of inspiration for Dostoevsky’s account of gambling addiction in ‘The Gambler’

Memorable characters, intuitive psychological study and social engagement justify the inclusion of this story in numerous anthologies. Once again, the most remarkable aspect for me is how much Pushkin can do with so few words, when they are chosen carefully.

How salty is the taste of another’s bread, said Dante, and how hard it is going up and down another’s stairs – and who has a better understanding of dependence than the poor ward of a grand dame?

A wealthy Countess with a terrible reputation at the Court of France is spending her twilight years abusing her servants and the young girl that she has hired as her companion. Elsewhere in town, a group of young men playing cards discuss a rumour that the Countess has a sort of pact with the Devil to gain a sure method of winning at the casino. One of the men, an engineer named Hermann, decides he wants to do something about it, so he sets out to seduce the impressionable girl and gain access to the Countess through her.

Two fixed ideas cannot coexist in the moral world just as two bodies in the physical world cannot occupy the same space.

>>><<<>>><<<

How relevant is Pushkin to the modern reader? This is a question every reader should decide on their own. I’m glad for my brief visit, and once again I wish the day would have twice as many hours in it so I could read all the stuff that appeals to me, like the rest of his short stories.

“Paul!” the Countess called out from behind the screen. “Send me another novel, but not one of those modern ones.”

“What do you mean, grand’maman?

“I mean a novel in which the hero doesn’t strangle his father or his mother, and there aren’t any drowned bodies. I cannot abide drowned bodies.”

[is this a dig at Emile Zola and Thomas Hardy?]