What do you think?

Rate this book

168 pages, Hæftet

First published March 28, 2014

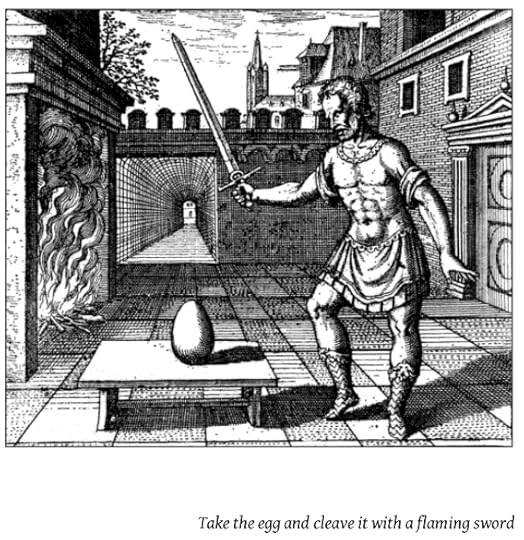

Tycho Brahe had the same urge to control nature. In one of his poems, he writes about capturing the Muse of Heaven (Urania) and imprisoning her in his castle that was called Uraniborg. Nature personified as a woman and then this figure of the male conqueror. But, unlike Pliny, Tycho made real changes and his work had enormous consequences, shattering the whole vision of the universe of his day, and challenging the notion of eternity. There was a doubleness to him as well. He was both the exact scientist and a mystic; an astrologer and an alchemist.

When I found the Meteorological Diary, I knew I had to write about [Brahe]. It consists of meteorological notes taken by Brahe’s assistants over a span of 15 years on the island of Hven. It is mostly about the weather, but occasionally there are glimpses of life in Brahe’s castle Uraniborg. That book gave me the form [...] I wanted to follow the year, month by month, in the style of a Renaissance almanack. These almanacks often contained illustrations, poems, and stories in between the descriptions of the months of the agricultural year, so it gave room for different narrators and styles.

I only saw Master Brahe in the seated position, but it is my impression that he is at once fat and hunched, thus manifesting the worst traits of both the noble and the learned. His speech is nasal, even shrill, perhaps as a consequence of his having lost part of his nose in a duel, a section now patched with a leaf made of bent metal and smeared in rosy ointment.

Dark rain almost the entire day; evening sky red after ☉ had set, though dark at night, southeast. I walked down to the beach with Jakob at sunset. We skipped stones under the smouldering clouds and played bare-foot, gathered shells and pebbles to make patterns near the waterline, and screamed at the waves when they took away our designs. [51]