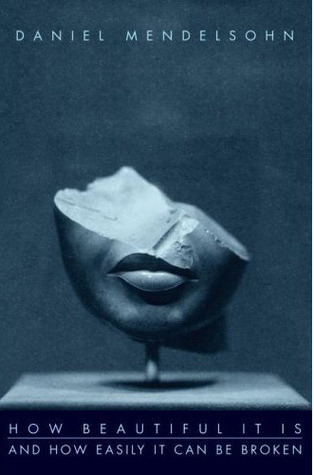

What do you think?

Rate this book

456 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 2008

(1) Meaningful coherence of form and content;

(2) Precise employment of detail to support (1);

(3) Vigor and clarity of expression; and

(4) Seriousness of purpose (p. xv)