Miss Julie, whose last name we never learn, is the daughter of a Swedish count. The whole point of the title of this 1888 play is that she is “Miss Julie” to anyone who is “below” her on the socioeconomic scale of late-19th-century Sweden. With her aristocratic status, all Miss Julie has to do is follow the unspoken rules of her society for upper-class women; if she does so, a comfortable life is seemingly assured for her. But she does not end up following her society’s norms for women of the aristocracy, and the process of her fall is set forth mercilessly by August Strindberg over the course of his play Miss Julie.

Long before he wrote Fröken Julie, August Strindberg had established himself as Sweden’s premier playwright. Like his contemporary Henrik Ibsen in Norway, Strindberg crafted tough-minded, uncompromising dramas, with modern settings, characters drawn from ordinary life, and subject matter that might have been considered unthinkable for the more “respectable” playgoing of an earlier time. Today, the Strindberg Museum, in the playwright’s home on Drottninggatan in Stockholm, is still a site of pilgrimage for lovers of literature and drama from all over the world – a testament to Strindberg’s continuing power and influence.

Strindberg was drawn to naturalism – that particularly bleak form of realism that looks at human behaviour as being nothing more than programmed response to deterministic drives – and his naturalistic philosophy comes forth unmistakably in a preface that he wrote for Miss Julie. Regarding his method of characterization, he writes that “My souls (or characters) are conglomerates, made up of past and present stages of civilization, scraps of humanity, torn-off pieces of Sunday clothing turned into rags – all patched together, as is the human soul itself” (p. 13). With regard to plotline, he states that “I find the joy of life in its violent and cruel struggles, and my pleasure lies in knowing something and learning something” (p. 12). Those pithy statements, from an author who is more than capable of distancing himself from his characters, prepare the playgoer or reader for Miss Julie.

The play takes place in the kitchen of the country house of Miss Julie’s aristocratic father, on Midsummer’s Eve. That holiday, in the Sweden of those times, was an occasion when the ordinarily rigid barriers between people from different social classes might be relaxed somewhat – rather like the festival of the Saturnalia in imperial Rome. And from the beginning of Miss Julie, familiarity between people of differing socioeconomic status is central to the play.

As the play begins, two members of the count’s household – 35-year-old cook Christine and 30-year-old valet Jean – are talking about what they describe as the “crazy” behaviour of 25-year-old Miss Julie, the count’s daughter, during the fortnight since the breaking of her engagement. Jean remarks on Julie’s recent tendency to spend time around the servants, stating that “It’s peculiar…that a young lady – hmmm! – would rather stay at home with the servants…than go with her father to their relatives!” Christine, in turn, feels that Julie may be “sort of embarrassed by that rumpus with her fellow” (p. 27).

What Jean knows, and Christine does not, is exactly what led to the breakup of Julie’s engagement. Jean tells Christine (with whom he has an unspoken engagement) that Julie and her fiancé “were in the stable-yard one evening, and the young lady was training him, as she called it. Do you know what that meant? She made him leap over her horsewhip, the way you teach a dog to jump. Twice he jumped, and got a cut each time. The third time, he took the whip out of her hand and broke it into a thousand bits. And then he got out!” (p. 27).

Julie’s dehumanizing treatment of her fiancé – treating him as if he were an animal, to be trained with a whip – hints at a certain contradictory element in her nature. Why would she behave in a way that was virtually certain to derail a suitable and advantageous marital match? I thought, in this connection, of Edgar Allan Poe’s suggestion, in his story “The Imp of the Perverse,” that there might be a certain element of perversity in human nature that causes human beings to willfully engage in behaviour that they know will harm them. I thought also of Sigmund Freud’s ideas of the thanatos, the death-drive.

But there needs no Poe come from Baltimore, no Freud come from Vienna, for us to be aware that there is something unusual, and potentially self-destructive, about the way Julie is behaving.

Most of the play takes the form of an extended conversation between Julie and Jean, during most of which Christine is outside of the room. We learn that Jean, while of “lower” socioeconomic status, has strengths of his own; he speaks French at least as well as Julie does, and he has travelled internationally.

Jean is acutely conscious of being of a lower socioeconomic status, talking of how Julie, for him, “symbolized the hopelessness of trying to get out of the class into which I was born” (p. 48). Yet he has ambitions of rising above his station, stating that “I know that if I could only reach that first branch, then I should go right on to the top as on a ladder. I have not reached it yet, but I am going to, if it only be in my dreams” (p. 42). He describes his tactics for learning the ways of the aristocrats he would like to walk among as an equal: “I have listened to the talk of better-class people, and from that I have learned most of all” (pp. 48-49).

Julie meanwhile seems to enjoy flirting with Jean – asking him for a dance, watching him closely, touching his arm, and praising his muscular strength. Jean cautions Julie regarding her behaviour, but does not flee the room.

A crisis in the action of the drama occurs when Julie and Jean find that a group of peasants, dancing and singing as part of their Midsummer’s Eve revels, are approaching the kitchen. Worried about what might happen if they are found together, they hide in Jean’s room. It takes some time for the peasants to finish their dancing and singing, and to leave the kitchen; and when Julie and Jean re-emerge from the privacy of Jean’s room, it is clear that their earlier flirtations have proceeded all the way to consummation.

Julie’s early feelings of joy and intimacy – she initially tells Jean to drop the “miss” and “Call me Julie” – are soon replaced by fear, as she comes to realize the potential consequences of what she has done. “Do you think I am going to stay under this roof as your concubine? Do you think I’ll let the people point their fingers at me? Do you think I can look at my father in the face after this? No, take me away from here, from all this humiliation and disgrace! – Oh, what have I done! My God, my God!” (p. 58) For his part, Jean feels that his place in the house is likewise compromised by what he and Julie have done, and says that he sees no way that the two of them can both stay there.

Things turn very ugly between Jean and Julie, very quickly. Julie tries to pull rank on Jean: “You lackey, you menial, stand up when I talk to you!” In response, Jean asks, “Do you think any servant girl would go for a man as you did? Did you ever see a girl of my class throw herself at anybody in that way? I have never seen the like of it except among beasts and prostitutes” (p. 63). It is painful, scarring, to see two people verbally flaying one another in this way – and even more painful and scarring, upon further reflection, to imagine what comparably bitter arguments are no doubt unfolding right now, even as we speak, between two people bound by a former intimacy and locked in mutual hatred. My hope for you, friend reader, is that you never, ever, ever find yourself in an argument like the one that unfolds between Julie and Jean in this play.

One can consider Jean’s and Julie’s verbal battles in terms of something that Strindberg writes in his preface for the play: “Jean stands above Miss Julia not only because his fate is in ascendancy, but because he is a man. Sexually he is the aristocrat because of his male strength, his more finely developed senses, and his capacity for taking the initiative. His inferiority depends mainly on the temporary social environment in which he has to live, and which he can probably shed together with the valet’s livery” (p. 17).

At the same time, though, I find myself reminding myself to trust the tale and not the teller. Strindberg may feel that Jean is better equipped to survive in a Darwinian natural-selection battle for the survival of the fittest, but there are indications in the play that Jean, like Julie, is a creature molded by his environment. At one point, Jean says of his employer the count that “If I only catch sight of his gloves on a chair I feel small. If I only hear that bell up there, I jump like a shy horse. And even now, when I see his boots standing there so stiff and perky, it is as if something made my back bend” (p. 56). And when it becomes clear that the count (who is never actually seen in the play) has returned, Jean shows a craven, subservient side of himself that is quite different from the assured sexual conqueror hurling cruel insults at Julie.

So can Jean really rise above his station, as he dreams of doing? Perhaps – if he relocates to Minneapolis/St. Paul, or Winnipeg, and makes a new start in a new land. If he stays in Sweden, I can’t help thinking that things may stay very much the same for him.

As for the “fallen” Miss Julie, she reveals to Jean that her family’s seemingly assured place in the Swedish aristocracy in fact reflects a turbulent family history. From her mother, Julie tells Jean, “I learned to suspect and hate men – for she hated the whole sex, as you have probably heard – and I promised her on my oath that I would never become a man’s slave” (p. 69). It becomes evident that her contradictory behaviour, in the world of the play, is, at least in part, a result of the contradictory influences that have molded her character.

A desperate Julie beseeches Jean: “I can’t leave! I can’t stay! Help me! I am so tired, so fearfully tired. Give me orders! Set me going, for I can no longer think, no longer act –” (p. 76). In response, Jean emphasizes the change in their relative status: “Do you see now what good-for-nothings you are! Why do you strut and turn up your noses as if you were the lords of creation? Well, I am going to give you orders. Go up and dress. Get some travelling money, and then come back again” (p. 76). There is some talk of the two decamping together to Switzerland, using some of the count’s money to start a hotel; but as the play moves toward its conclusion, one gets a strong sense that there is no future for the unfortunate Miss Julie.

Looking back on Miss Julie’s sad fate, Strindberg reflects that “The fact that the heroine arouses our pity depends only on our weakness in not being able to resist the sense of fear that the same fate could befall ourselves” (p. 11). It is a modern twist, with a naturalistic orientation, on Aristotle’s idea of catharsis – a purging, for the audience, of the emotions of pity and fear that are aroused by witnessing a tragic drama.

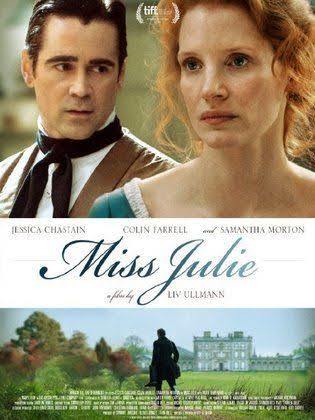

Miss Julie is still very much with us. Strindberg’s play has been filmed twice in recent years – once in 1995, by Leaving Las Vegas director Mike Figgis, and once in 2014, by Swedish actress and filmmaker Liv Ullmann, who cast Jessica Chastain as Julie and Colin Farrell as Jean. What has drawn all this movie-making talent to a play that – with only three speaking parts, and only one setting – seems singularly ill-suited for cinema? Perhaps it is, purely and simply, the singular dramatic intensity of this work. With no scene breaks, no intermission, Miss Julie leaves us with no escape from the starkness of the emotions it evokes. It may be set on Midsummer’s Eve, but it is a play suffused with the chill of a particularly bleak emotional winter.