Once, when my son was about fifteen, he turned to me at a piano competition and said, “Mom, there are just so many people.”

I remember looking up from a book, looking around the room at a sea of sweaty competitors and then bringing in my gaze to stare at the terror in my son's face. Privately, I shared his terror. Who could do this? Who could memorize and then perform these required pieces in front of judges and peers? I find this aspect of my son's life bewildering, but I'm his mother and my job is to help him stay centered.

So, I shared something like, “Look. Everyone here has talent. Probably everyone here has worked hard, too. They had to, to get here, to this point. What's different about each of you is how you interpret your pieces. It's up to the judges to determine their favorite interpretations. You can't do anything about this now, but be yourself.”

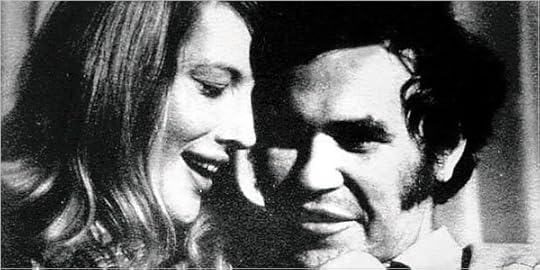

This week, I found an essay, “On Writing” from this Raymond Carver collection that seemed to echo my sentiments to my son:

Some writers have a bunch of talent; I don't know any writers who are without it. But a unique and exact way of looking at things, and finding the right context for expressing that way of looking, that's something else. . . Every great or even very good writer makes the world over according to his own specifications. It's akin to style, what I'm talking about, but it isn't style alone. It is the writer's particular and unmistakable signature on everything he writes. It is his world and no other. This is one of the things that distinguishes one writer from another. Not talent. There's plenty of that around. But a writer who has some special way of looking at things and who gives artistic expression to that way of looking: that writer may be around for a time.

Wow. There it is. That advice, and so brilliant for all of us, always, to remember it. But, wait, there's more. . .

Mr. Carver then goes on, in his essay “Fires,” to capture my exact feelings on “the ferocious years of parenting” and manages to encapsulate my joy, my terror, and my guilt in wanting to give my children and my writing equal parts of my time. He points out that this is an impossible goal, and for those of us who have put our children first in our lives, all endeavors after will suffer, regardless of how much we want them to succeed.

A male writer expressing such thoughts. . . in the 1970s no less.

Who is this guy? My soul mate??

And, then. . . and, then. . . after his essays, he offers a section of some of his inspired verse. And, folks, if you don't get why this particular poem is great, then you'll probably never understand poetry:

The mallard ducks are down

for the night. They chuckle

in their sleep and dream of Mexico

and Honduras. Watercress

nods in the irrigation ditch

and the tules slump forward, heavy

with blackbirds.

Rice fields float under the moon.

Even the wet maple leaves cling

to my windshield. I tell you Maryann,

I am happy.

(Highway 99E From Chico)

Then he offers, at the end, seven works of short fiction, much of it forgettable for me (explaining here the four stars instead of five), but the collection ends with a bang with the brilliant "So Much Water So Close to Home." I'd prefer to revisit that story in What We Talk About When We Talk About Love at another time.

For now. . . Mr. Carver,

put down your beer

your cigarette, too.

I want nothing between your mouth

and me.

I'm a little in love, sir.