What do you think?

Rate this book

272 pages, Paperback

Published June 10, 2025

‘The night before we joined up, I thought we should do something different, and tried to drag him to Kentucky Fried Chicken (which these days, seems to only be branded with its initials). He batted away my suggestion. ‘That ang moh food doesn’t sound tasty. It’s only chicken, after all.’ I’d seen many billboard ads promising it would be ‘finger-lickin’ good’, and insisted that we try it at least once. After we went into the rainforest, who knew when we’d ever emerge again?’

‘I’ve always thought that linguistic consistency is a virtue more prized by people from monolingual societies, which I very much am not. Life in Singapore and Malaysia takes place in a patchwork of many languages and cultures, a multitude reflected in Hai Fan’s writing—with its fragments of many Chineses, transliterated Malay, English, and Thai words—and also in this translation.’ (Translator’s Note)

‘In the farming villages, the Minyun volunteers were on the move, arriving almost every day with supplies for the festive meal. Basket after basket of nine-pound chickens passed by the sentry post, the fowl clucking away on the backs of comrades who couldn’t stop grinning—All year round, the comrades subsisted on mixed grains with every meal, but at this festive time, they would have a few days to enjoy white rice served with delicious dishes: white-poached chicken, Guangxi stewed pork, kelah merah fish from the croplands, all kinds of fresh fruit and vegetables… As the ingredients were carried past everyone’s eyes, their tongues danced with memories of delicious flavours, heightening anticipation for the holiday.’

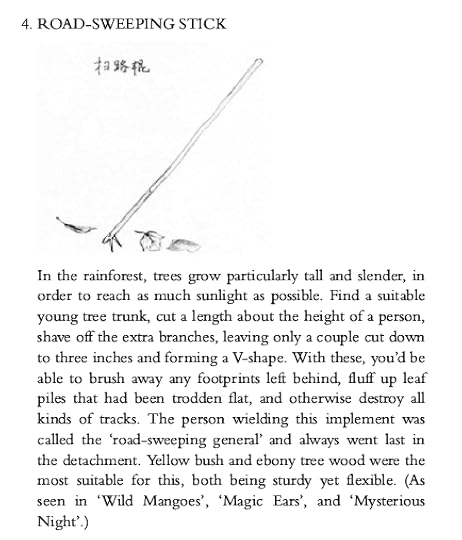

‘As he handed her his road-sweeping stick, he detected the dull reek of blood, mixed with the muddy stench of the river. The tea-coloured water swirling around Lianyi’s trouser legs was momentarily stained with red-brown liquid that quickly dispersed. Right away, he understood why Lianyi had insisted on crossing alone. Lianyi limped away from him, shaking as she reached the other bank.’

‘Between the rain, the river, and this sodden uniform, there was no way to keep it hidden—she could smell the odour on herself. Her only choice was to hang back from the rest of the group. She tried to work out from Yejin’s face what he was thinking. Surely he could tell. But he sincerely wanted to help, and was stronger than her. Should she let him carry some of her load in his rucksack? Or just swap her cargo with his?’

‘The synergy between Hai Fan and translator Jeremy Tiang is palpable when you read the text. The experiments that the translation into English presented was in stretching the form of the work into zig zags and poetic enjambment to feel at one with the rainforest, while retaining Hai Fan’s deliberateness with his matter-of-fact tone and emphasis on the ridge of a combat knife or the headiness of someone’s sweat in close quarters. Something that has been on my mind while working on this text has been the thought of coping networks during condensed periods of violence and grief—Without a coping network, without his home in the rainforest (he) becomes a ‘stray cat’. We are invited into a collection where coping continually changes shape.’ (Editor’s Note)

‘Names are unstable, arbitrary things. As noted in the book, the comrades all took on new names upon entering the rainforest, partly to symbolise a new beginning, partly to shield their previous identities so no one could implicate anyone else. These names often had a significance of their own, with comrades who joined up at the same time adopting names with one character in common. While there was little consistency in the romanisation of names at the time—’ (Translator’s Note)

‘‘Bulldozing forests just so that rich people can go on vacation is not nothing. We have the most ancient jungles in the world, older than the Amazon, older than anywhere else on the planet, and we cut them down to build, what, Tivoli Villas? The fuck.’

Chuan sighed. ‘What’s the point of fighting if the fight is already over? No one cares about us. We’re a small country, we’re not Brazil. The world wants brand-name causes. The Amazon is a brand. We’re not sexy. We’re invisible.’

‘But we exist,’ Yin said, quickening her step to walk abreast of Lina.’ — from The South by Tash Aw

‘She was having a tough time searching for the little temple. Back in the day, this Goddess of Mercy temple had been in Marsiling kampong. She remembered an old banyan tree by the entrance gate, shady leaves rustling and long tendrils swaying. Now, though, she couldn’t quite remember how to get there. In the last few years, she’d set foot in virtually all the temples she knew of on this small island, and even offered incense more than once at the Old Temple in Johor Bahru, at the other end of the Causeway.’

‘Clasping her hands, she’d allowed her eyes to drift upward. The Goddess of Mercy, cross-legged on her lotus throne, looked down at humanity with her usual benevolence. Just one glance, then she shut her eyes to pray. That one look was enough to take in the purple haze that enveloped the Goddess. In the many years since, that purple glow had often drifted into her dreams. If she hadn’t believed, she wouldn’t be here today.’

‘Life is a single-lane road, and each of us walks through different landscapes. Even if you’re travelling alone, you’ll have different identities on different stretches of this road. Could there be a magical pathway that would allow us to meet with our past selves? To pick up these memories and rip them to shreds, mix them together, sculpt them again… Could this not be a process of getting to know ourselves? And so I am publishing this book at this time, not just to obey the urgings of my heart but also to hear the responses from readers and the life around me. The stories beyond the stories.’ (Author’s Note)

‘I’ll write you a letter,’ he said, ‘if you give me your burden.’