3, maybe 3.5. Roundabout there.

This is the novel that folks have told me to read when they've read my reviews of Bentley Little. The Little Novel, as it were. Little to me is something of a conundrum. My first taste of his fiction, The Store, I liked. I liked the strange imagery blended with visceral horror, and I liked the sense that underneath it all he wasn't so much a horror author but a satirist, one who punctuated his jokes with gore and suffering. Bentley Little might just be the reductio ad absurdum of the old Mel Brooks line (I'm paraphrasing) about cutting your hand being a tragedy, while you falling down an open sewer and dying being a comedy. The whole slant of the novel, which on the surface read was about a demonic department store destroying the fabric of a small town, felt a bit like a mockery of the new America, the new American family, the new American male, and the new American cowardice: our belief in authority, in truth, in things working out if we just wait the weird long enough.

As I read more by him, though, it soured. The template repeated. The "joke" was the same. Family man loses control of the situation (and his family and - largely metaphorically, though I doubt always - his penis) as some everyday instance, some new fact of American life, is perverted and twisted and embiggened until it is a caricature of our new fears, a breathing demonic form of our existential dread in dealing with the day to day existing in this world with its plastic and neon and television adverts and 401ks. His visceral glee has punch, has power, but it traps itself in certain patterns, certain themes.

Thus, The Mailman, The Little Novel, the one that would perhaps open up my eyes. And, truth be told, it is my favorite Bentley Little novel. The central conceit is strikingly brilliant - even if it had ceased to be as viable a few years after the novel was written, and was perhaps not as viable as it seemed even when the novel was written: what does a small, somewhat isolated town do when someone/something completely alters the mail? Bills and important letters go missing. In its place, is mail that carries a darker tone, nearly subtle at first, increasingly warped and depraved over time. Letters from neighbors carry threats, terrible secrets, sexual perversions. Letters from colleagues revel in disdain, spew hate, belittle (ha, pun!), and wound. Dead relatives send horrid pictures (or show up, piece by piece). Loved ones tell you they despise you. The entire flow of information becomes the plaything of a single, seemingly innocuous figure: the mailman.

Nowadays you could substitute social media, and experiments conducted where Facebook ok'd some folks getting more negative news and some getting more positive. Or parallels in state censorship, Agitprop. Twitter bots. Et cetera.

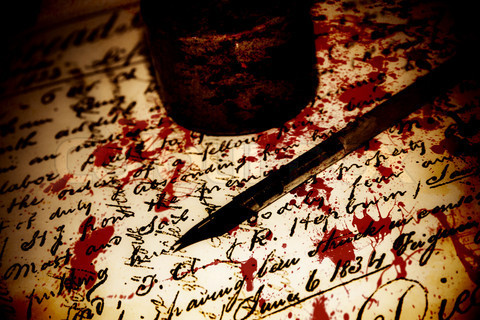

In the midst of this, you factor a certain ineffectiveness of authority, a certain holding to company line, a failure of those in charge to be in charge when things don't run themselves, a distrust of those nearest you. In other words, you expose the machine and all its gears and cogs and rules and instructions as a blind idiot god merely dancing to the mad piping of flutes as the little people - the ones who have to worship it and pray to it and feed it with their flesh and time to survive - are forced to emulate a world in which said machine is real, has power, and has meaning. The machine becomes a fiction, a madman fantasy, and the faith in it drives those underneath into a widening gyre. This is the satire that I sense, however correctly or incorrectly, boiling inside of Little's fiction. A great Kafka-esque joke that you cannot even laugh at, a Dionysian comedy full of angry wine and shouts and blood.

Just look at the "solution" to the problem of this novel, the fighting back against the evil, and dance with joy at its simple inanity and delightful brilliance; its message of the people and the rejection of the machine.

The weakness, though, is in the pattern that Little weaves. The reliance on easy triggers. The repetition of certain punches. Though less present here than in other things I have read by him, this novel again evokes the spectre of castration, the reduction of the modern male into a dickless thing (see, among other places, the man character's despair that he cannot be there when his son needs him, and how the wife must make up his lacks, and why this means children are drawn to their mother for protection). This novel so overuses gory child rape that it almost starts normalizing the shock. Sexual violence, in general, is too easy a tool, here, and even Little's attempts to make particularly violent does not save it from a sense of cheapness. Suicides with brains splattered: why stop at one? Why cut open one young woman when you cut up multiples? Going to kill a dog, kill several! Rinse! Repeat!

If you told me Little was trying to bash these cookie cutter shocks into the readers' brains until they ceased to have meaning, that this was a dive into a surreal Grand Guignol where the audience's own inability to continue engaging in the horror was the true horror, I'd nearly believe it. Even in the scope of a single book, the hits keep falling into the same old pigeonholes. Across several books, the patterns continue. It becomes very nearly neoclassical in its mathematics, its use of structure, the Bentley Little alphabet of betrayal (by us, by the system, by the minimum wage workers and middle management that should help us to feel empowered).

The savior of these novels is the sheer glee in which the aforementioned everyday [perverted, exploded, corrupted] thing is displayed, the skewed take on officious, smiling drones in the capitalist world. Even if one grows a little tired of his unhelpful, uniformed-and-nametag-wearing entities acting as masks for demonic powers, one can appreciate the artistic stroke that makes those little smiles, those little pitying comments, those appeals to page after page of official policy, those refusals to check the back to see if some sweater you really want is there or not...into something so sinister. Our everyday world is plagued by interactions with folks we slot into easy categories, we associate with their jobs and their stations, that we turn into automatons and targets for our disdain, targets for our ire and our own sense of failure when the machine does not give us our perceived due, when it makes us struggle against it. Little just turns that up a notch, says that we are right to see them as The Other (though usually it is simpler than that, they are other people, with other lives, and they in turn see us as equally fitting into slots: the bitchy customer, the unsatisfied tool, the paycheck). Their failure to respond to your potency, to bring you your steak, to give you extra towels in a timely fashion, to deliver your mail: in Little's world, this is the true evil. And it is up to us to stop them. Bless.

At any rate, this novel has a Chekov's grammar lesson in it...so it has that going for it.