What do you think?

Rate this book

282 pages, Kindle Edition

Published August 12, 2025

“Reading is a social experience, and today the experience is circumscribed by suspicion and groundless moral accusations” (p. 103).

“According to Bowker Market Research, young adults are not the biggest market for YA literature: ‘55% of buyers of works that publishers designate for kids aged 12 to 17—known as YA books—are 18 or older, with the largest segment aged 30 to 44, a group that alone accounted for 28% of YA sales. And adults aren’t just purchasing for others—when asked about the intended recipient, they report that 78% of the time they are purchasing for their own reading.’ Other sources estimate that ‘nearly 70 percent of all YA titles are purchased by adults.’ In large part, what people call the field of YA literature is a field of adults writing books for other adults. Given the reality that children under 12 are even less likely to buy books for themselves, and the other reality that some of these children cannot read books by themselves, the percentage of adult consumers is likely much higher for children’s literature. What I call the moral crusade over children’s and YA literature is, in large part, actually a moral crusade over literature written for adults.” (p. 116).

Introduction (p. 1).

Chapter 1: The Ideas of the Sensitivity Era (p. 9)

Chapter 2: The Behavior of the Sensitivity Era (p. 65)

Chapter 3: The Political Economy of the Sensitivity Era (p. 123)

Chapter 4: The Future of the Sensitivity Era (p. 169)

“Because the prophets of presentism carve the world into simple moral categories—following [Ibram X.] Kendi’s dictums, authors and their fictional characters are either racists or antiracists, sexists or feminists, and so on—both their lack of nuance and their disdain for classical literature are understandable. ‘In what is considered the first major literary theory in the history of Western ideas,’ writes Philippe Richat, ‘Aristotle (Poetics, 335 BCE) proposes that the essence of tragedy as a major literary genre is the main character’s moral ambiguity.’ Moral ambiguity is not just a feature of Dr. Faustus, Oedipus Rex, and other tragedies. It is a feature of countless plays, poems, and novels that belong to the Western canon, what Harold Bloom calls ‘the school of the ages.’ To use Romeo and Juliet or Grimm’s Fairy Tales as cheap props in the modern theater of moral finger snaps is to avoid the discomfort of trying to understand the moral complexities of these complicated works” (p. 41).

*

“Unlike Einstein, whose research was scrutinized and debated by other scientists, many sensitivity readers require authors, their agents, and their publishers to sign nondisclosure contracts. This prevents public evaluation of a sensitivity reader’s work. If public evaluation of one’s work is central to fields of expertise, then it is unclear how sensitivity reading is a field of expertise. It is especially unclear how it is a field of expertise on par with physics. Yet the science analogy extends from physics all the way through medicine. As author Natalia Sylvester explains, ‘Much like one might ask a cardiologist to read their story about a cardiologist for accuracy, a sensitivity read helps ensure that the portrayal of characters and worlds unknown to the author ring true.’ Other authors believe that there is no difference between sensitivity readers and medical professionals at all. As a contributor to #WritingCommunity reflects, 'If I were writing about a doctor, I’d get a doctor to beta [read] it to make sure I got it right. Same difference.’” (p. 57).

*

“If a reader wants to purchase Keira Drake’s debut YA novel to form their own interpretation of it, like a thinking person, it means they support racism. If, however, they rate an unpublished novel based on a short Tumblr post and some screenshotted tweets, like an unthinking person, it means they are against racism. What one agent of color described to me as the ‘contingent of people taking issue—whether they read the book or not’ is what antiracism looks like on Twitter, Tumblr, and Goodreads. When ‘real lives’ are on the line, there is no time for reading. There is no time for thinking. Above all, there is no time for different interpretations. Like the moral crusade over comic books [in the late 1940s and early 1950s], there is only time to damage a writer’s reputation.” (pp. 71-2).

*

“Many sensitivity readers earn more per hour than public school teachers, daycare workers, bus drivers, firefighters, dentists, and doctors. According to one University, ‘As of March 2019 the average pay for a sensitivity reader was $0.0005-$0.01 per word. For a work of 60,000 words, you can expect to receive between $300 to $600.’ At an average reading speed of 250 words/minute, a 60,000-word manuscript will take four hours to read. This means sensitivity readers can make an average of $75 to $150 per hour. If they work 40 hours/week, they can make between $156,000 and $312,000 per year.” (p. 131).

*

“When moral entrepreneurs are not demanding a ‘seat at the table,’ they are pushing Sensitivity Inc.’s products. The biggest products are new definitions of racism, homophobia, patriarchy, and other buzzwords.. It is no coincidence that the largest redefinition mills—journalism and academia—cannot function without new content. Despite their dignified postures, journalists are just as much a part of capitalism as people who sell Air Jordans, iPhones, and pornography. They have to constantly produce new content.

This is especially true in the era of fast journalism where op-eds have taken the place of long-form, reported stories that take months to research and write. When a journalist, and I use that term loosely, purports to ‘unpack’ what Stephen King’s newest novel really means, by redefining what ableism or misogyny really mean, they are able to meet their Monday morning deadline. [...] At newspapers and magazines with slashed budgets, where fewer writers are responsible for more content, cultural criticism is grist for the mill. At websites where writers have to churn out a dozen or more op-eds per day—this is the model for click-driven advertising dollars—they only have time to write op-eds like ‘This Fantasy Novel is Fatphobic.’” (p. 144-5).

*

“There is a similarity between this ‘antiracism’ and the New Age spiritual circles one finds in San Francisco, Brooklyn, Madison, Boulder, and other places where affluent white liberals in gentrified neighborhoods gather to talk about their feelings. Throughout, one gets the impression that white people are more interested in looking in the mirror—a perennial source of embarrassment for ‘whiteness studies,’ given its aspiration to decenter ‘whiteness’ —than doing anything that even vaguely resembles political activism.” (p. 147).

*

The author acknowledges that in the United States, conservatives “are leading the legislative fight to censor books they dislike. Even a cursory glance at data from the American Library Association (ALA) will familiarize readers with the conservative crusade to ban children’s and YA books in libraries and schools. Whereas many liberals are driven by essentialism and presentism, many conservatives are driven by nostalgia for a moment when books were less progressive and authors and their characters less diverse.” (pp. 165-6).

*

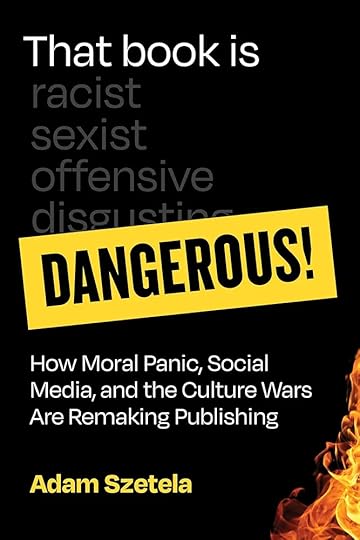

“The prevalence with which people freely admit they never read, nor have any intention of reading, books they passionately criticize is another indicator of how decrepitly anti-intellectual literary culture has become. In the past, publicly announcing that you have no idea what you are talking about, because you have never encountered the object of discussion, would have been an embarrassing omission. Even the food critics of Yelp stick to reviewing restaurants they ate at. Today, the omission is worn as a badge of pride. Above all, That Book Is Dangerous! is a case for reading books. That one has to make a case for reading books should indicate the stakes of this moral panic.” (p. 182).

*

“13. I do not capitalize ‘black’ for the same reason that other writers do not capitalize ‘black.’ In his preface to Revolutionaries to Race Race Leaders: Black Power and the Making of African American Politics, political scientist Cedric Johnson, himself a black writer, elaborates: ‘My usage reflects the view that racial identity is the product of historically unique power configurations and material conditions. This view contradicts the literary practice common to much Black Power activism, where racial descriptors are capitalized to denote distinctive, coherent political community and assert affirmative racial thinking.’ Cedric Johnson,Revolutionaries to Race Race Leaders: Black Power and the Making of African American Politics (Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2007), xvii.” (p. 206).