What do you think?

Rate this book

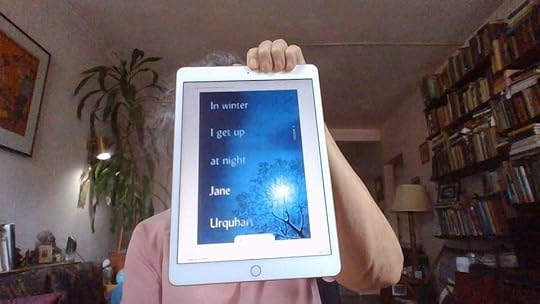

11 pages, Audiobook

First published August 27, 2024

As a child it would put me in mind of a line of that poem that had been read aloud to us by our poetry-loving Master back in Ontario: “‘In winter I get up at night ,’” he had begun, “‘and dress by yellow candle-light.’” Then came the musical rhythm of poetics, with a onesyllabled final verse that began with the line “‘And does it not seem hard to you?’”

My family, whose ancestors had endured the outlawing of their language and religion, the imperial takeover of their land, and the peril of famine, could never free themselves from property hunger. They gobbled up land in Ontario, field by field. Then they sent my father out to feast on the prairies in a similar fashion. All this without giving more than a passing thought to those who had for millennia inhabited the geography my family coveted. One tribe, forced out of its homeland by imperial dominance, war, and scarcity, migrates across the sea and forces another tribe out of its homeland.

When I think of the scene now, my legs braided with Harp’s, my head on his arm, speaking about my brother, it seems to come from a country so far away and visited so long ago, no memory can recover its shorelines. Harp’s long body. And that woman who was me, not young, but so much younger than I am now. What of her? How did she manage it all? The man, his body. No one before or after. I was helpless and adrift. He was unknowable. And that meant there wasn’t any part of me that I didn’t want him to understand, to know.

How strange we all are! Most of us come from Irish and Scottish tribes cast out by the mother country. But we are still reading her poems and singing her songs. How odd that we define foreignness as those whose speech hold the trace of another language, and then we ignore altogether our own foreignness on land that was never our own.

In winter I get up at night

And dress by yellow candle-light.

In summer, quite the other way,

I have to go to bed by day. - "Bed in Summer" from A Child's Garden of Verses (1885) by Robert Louis Stevenson (1850-1894).