What do you think?

Rate this book

240 pages, Paperback

First published October 7, 2025

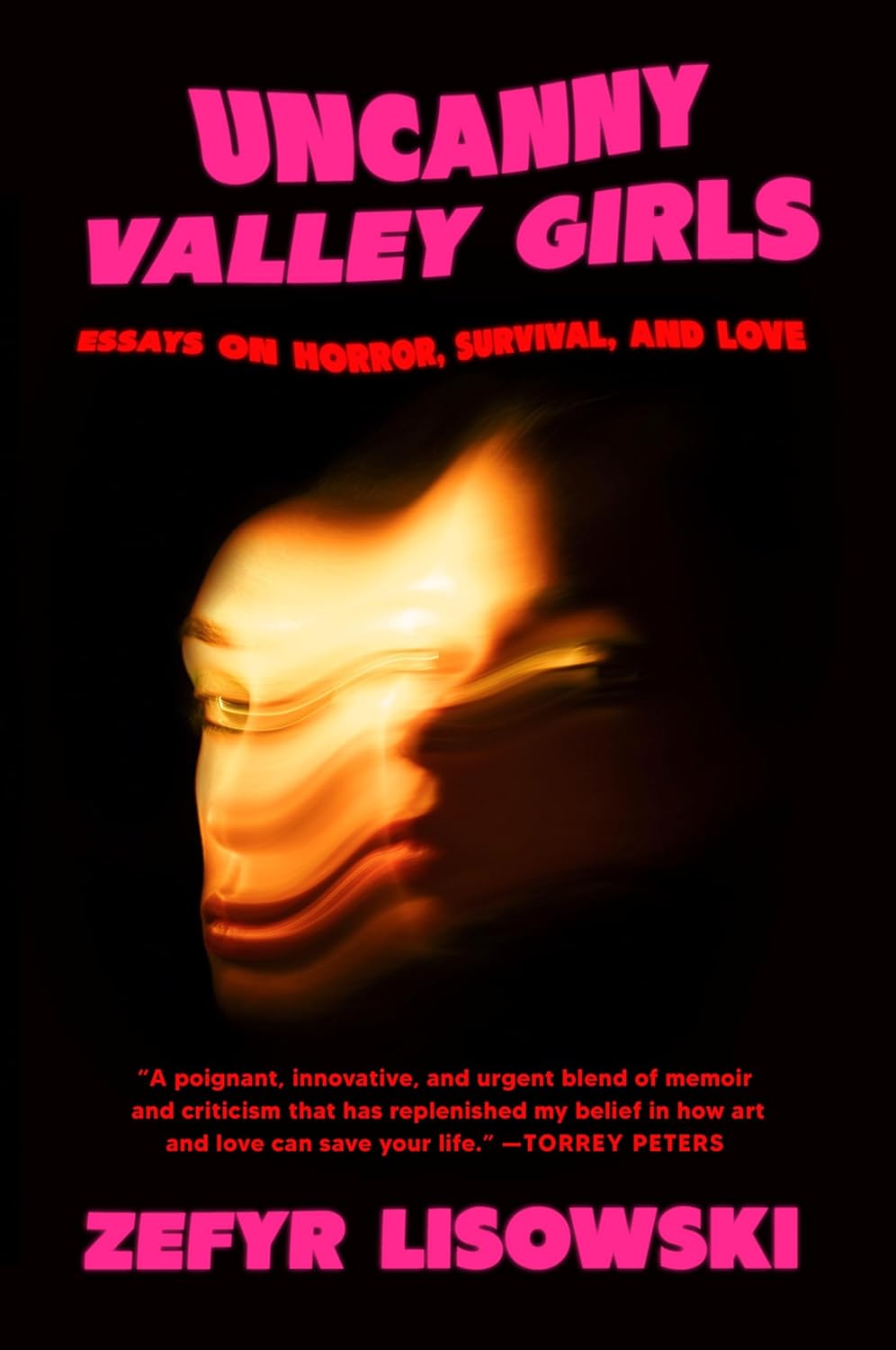

‘Horror movies are about staying alive, and that focus has taught me more about care than anything else. Through horror, you can see everything in life: atmosphere and pain and death and above all the desire to keep living. And in who you watch horror with—because few people I know watch scary movies alone—you can see the rest of it, too: the sex and guilt and grief and everything else that goes into loving yourself and others. I thought of each of my past relationships and of the movies we watched and the ways we reached for each other in the things that wounded us—’

‘The miracle is our capacity to live and love despite this wounding—To be afraid is to care, deeply, about whatever you’re afraid of; or, to be more succinct, to be afraid is to care. Scary movies, I believe, can teach you how to live. They can show you the lives you’ve already led. They can promise what a new horizon looks like. They’re how I survived.’

‘A point The Ring makes inadvertently is how interconnected all monstrosities are. The young dead girl who’s the villain is different and sick, so she becomes a recipient of violence—locked up in a barn, surveilled and neglected in the medical facilities that became her other home. And because she’s a recipient of violence, she becomes an enactor of violence. It’s important to note that the vehicle for her curse, the videotape, is a depiction of her own pain. Only after she’s murdered does she start to kill.’

‘What does it mean to “share a cold” instead of shutting it away? I’m inspired by all the small dominions we, the disabled, have, how much has been shared already. Money. GoFundMes. Personal care assistants. Lists of accessible events spaces. Mutual care and love and support. Knowledge is shared openly online and in group texts and over encrypted chats and through webs of in-person and digitized gossip. Disabled people have created a whole wellspring of culture and activism and vitality—and that buried truth is part of what makes us scary to the abled mainstream. Both Samara and Zelda have full interiorities that the movies cannot see—but that shadow of something beyond the protagonists’ comprehension is part of what makes them scary. They endure despite those in power wanting them dead. My partner had chronic pain, as well, and as we fucked during Pet Semetary that Halloween in 2015, it, too, felt like a kind of love that rejected charity. Sick bodies doing what they do, refusing to be stifled—together—is a radical act.’

‘I’m grateful for the anger that propelled this making in the first place. But even still, I have to wonder what my life would be like had I never been exposed to these supremacist messages in the first place. Here’s one last little story. In The Ring, when the girl climbs up the well, her bones cracking out of place, bending behind herself, this is supposed to be a sign she’s to be feared and pitied and isn’t even human. When I discovered, suddenly as a child, that I could do the same thing, oh, it felt like freedom.’

‘Horror movies live in the interregnum of the uncanny, a world ripe with anticipation. This is why they are so frightening. They are close enough to unnerve, and like a mirror they reflect us back—distorted into something strange and new. But isn’t that love, too? Doesn’t everything worth doing change you?’

‘In Black Swan, the protagonist dies at the end. Nina dies, the movie suggests, because she can’t change while the world around her does. In this way she differs from most horror protagonists, who bend but rarely break to survive a violent world. Personal shibboleths against killing get discarded, shrinking violets turn into hardened women, but they survive despite, or because of, these changes. There’s a whole term for it, which the scholar Carol J. Clover coined in a 1987 essay: the final girl, the one who lives because of how she transforms.’

‘—I’d break into the big botanic garden at the outskirts of my neighborhood, scrambling over the fence and walking among hydrangeas bright and pale as the moon.’

‘And who hasn’t felt nostalgia for a place because it was where they first realized who they truly were? Who hasn’t found themselves in something they didn’t even realize they were looking for?’

‘For the longest time, I’d tell people I loved art-house films as a way of making my own desires seem more palatable: the movies of Apichatpong Weerasethakul or Ingmar Bergman or Terrence Malick or any other director who specialized in long, winding, thoughtful shots and barely restrained emotions. I’d tell them they helped me see the splendor of the world around me, how their restraint helped me see myself. I do love them, and it’s true that a part of me was found there. But of all the movies I’ve seen, I’ve found the most splendor in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, discovered myself the most in it—a revving engine of a film, sick and quick and all deep reds. In fact, this is how it worked: First I loved it, and then I loved myself.’

‘There are the marks that are left on us, and then there are the marks we leave on ourselves, and I’m still not sure if there’s a difference between the two. The South shaped me, and the South hurt me, but that doesn’t change the fact that I’m Southern and thus implicated in its own violence—raced and classed and sure as my own violence toward myself. Maybe there’s no difference at all between the social ostracization I received in the South and my rage at the other Southerners stuck in my small town and finally the punches I started to dole out to myself—all were motivated, after all, by a refusal to see the beauty in a harsh and beautiful environment.’

‘—it’s bright and yellow outside and the air smells like pine, and I’m starting to realize that everything about my life will have to change. The bruise throbs, and I wince, air sharp and cool as I inhale. Eventually I will learn to share that beauty, too, even though it’ll be years still before I stop harming myself. Soon, the sun will set. But for now the light comes into me like birdsong. Someday, I will be free.’

‘Who, in our country, could see that synchronicity in death and not think the only way out was through work? Cutting anything down can be a way to stay alive, but it can also distract from the other work of living as well—A life slivering bits away isn’t a life at all: In the aftermath—I’d feel alive and ashamed and above all still in pain, hiding in long-sleeve shirts and oversize pants splattered with the paint I covered the dollhouse in. It wasn’t purifying; it wasn’t redeeming; it just continued.’

‘But maybe I’m looking at this wrong. Things that aren’t a choice aren’t always a burden. Who hasn’t wanted to be stripped of agency but in, like, a hot way? Who hasn’t wanted to slide sure as a moon ascends in the skies towards something not you, something beautiful instead? Who hasn’t dreamed of a life beyond the moment of change, too?’

‘—in that moment—just for that moment—I felt safe and held and fully present in their arms. I turned to hold them back as I started to blur out once more. I could love this person, I thought. And then, everything started happening again, and I was gone.’

‘Faith, like desire, is rarely on your own terms: If you can only sometimes choose what you have faith in, you can never select what has faith in you—there briefly and then disappear—I gave it up, lasting six weeks before I stopped entirely. As much as I wanted to, I simply didn’t believe in the practice enough to stay. It shadowed me while I was lucky enough to hold it, and then, as quick as Maud’s own consumption in flames at the end of the film, it was gone.’

‘What stuck with me the most about Agatha’s life was the way she wasn’t restored to former glory the same way other saints were. In most icons of her, she floats holding her severed breasts on a plate. Peace, God, whatever: I knew she was propaganda to prevent women from reacting more strongly to men’s shit, but even still. The fact that something could be taken from her and she responded by putting her losses on display spoke to me before I even could register why.’

‘To be crazy is to know your life has been marked as less than by those in positions of power; to date other crazy people is to assert your life’s worth nonetheless. Antichrist is a comically misogynistic movie if you watch it from the man’s perspective; it’s a harrowing film if you watch it from the woman’s.’

‘Our beauty, constructed against a society that fetishizes and hates us in simultaneity, is abject, and Greer’s dolls are, too.’

‘Sometimes I wonder if we just reenact the same life patterns of those who haunt us—a two-way street: If grief is an act of love, then leaving a ghost of yourself behind is as well. Sharing an experience with someone who isn’t there anymore, I have to believe, is a way of communicating with them—’

‘For me, horror is a love language, but maybe that’s because for me everything is a love language. Horror at its most intimate is a way to share the secret parts of yourself with others: what frightens you, what comforts you, what you’re nonplussed by.

When I was a child, my greatest fear was losing who I was through what happened to me. And yes, I’ve lost myself again and again. But in the wake of the violence that shapes us, I’ve also found myself more fully than I ever could have without the wound.

Being in the present—which is to say, presence—implies a future, too; caring in that moment shapes that future. Presence makes a path to find future presence, too. It shows us a life, struggles linked in love and fear alike. Like a final girl, a sick girl, a girl in the well, I know I won’t heal from what I’ve done or what was done to me. But I’m not interested in being healed nor in my wounds being reopened: What I want now is to love the scars that make us us—’

‘A flash of blood transforming into hope. A girl turning into a wolf. A host of faceless women all marching up a hill. As I enter the clubhouse for dinner, I’ll only hear the unsteady metronome of the present—unknown, unwinding, scary, and free. Fear has a thumping rhythm to it, but so does being present with people you care about, and that’s what I choose to listen to now. I’ll walk to the dining table—sound of love rumbling underneath everything like a heater slowly clanking up to speed. Even if the French psychoanalysts are right and horror is about the rotten, the dead, the makeup-less, the sick; even if we’re confined to the abject, the unwell, the uncanny—that’s beautiful, too. Yes, I’ve lost myself through the things that have happened to me, but so have you. So I’ll sit down at the table with my new friends, far away from you, and you, and the you I haven’t met yet, and fix my plate and fill my belly, eating to satiation at last. Soon it will be completely dark outside and the coresidents will start trickling to bed. I’ll wash my plate, and while the other writers and artists start their nighttime routines, I’ll start my own: I’ll walk down by the lake again, dip my feet into the water, and think of the present to come. My legs, still healing, will throb from the exertion of walking down the hill, but that’s part of what being present means: accepting pain as a prerequisite for being alive.’