What do you think?

Rate this book

214 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1332

If I fail to say what lies on my mind it gives me a feeling of flatulence. – Kenkō (1285–1350)Kenkō, a fourteenth-century Japanese monk, courtier, poet, and antiquarian, had a lot on his mind. Retired from the tumult of the imperial court, he spent whole days alone in his cottage in Kyoto, jotting random, nonsensical thoughts on slips of paper that he pasted to the walls. After his death, these scraps were peeled away, sorted, and copied into a volume now known as Essays in Idleness (1332). These 243 epigrammatic articles, written to relieve a pressing and uncomfortable ennui, give us a fascinating glimpse into both the world of medieval Japan and the inner workings of one of that nation’s most forthright thinkers and influential stylists.

A flute made from a sandal a woman has worn will infallibly summon the autumn deer.Brief and of dubious practicality, these pithy observations nevertheless show us part of a mind that took an encyclopaedic interest in the world: Buddhist ritual, carp fishing, the education of courtiers, physical deformities, burning moxa on kneecaps, the beauty of dew-covered flowers in the morning, the best way to view the moon on cloudy nights ... just a few of the many thoughts that crowded his attention. Despite the author’s expectation that his pages would be ‘torn up, and no one is likely to see them’, their influence on how the Japanese regard behaviour and beauty – often one and the same – has been far from transitory.

On a day when you’ve eaten carp soup your sidelocks stay in place.

You should never put the new antlers of a deer to your nose and smell them. They have little insects that crawl into the nose and devour the brain.

When I sit down in quiet meditation, the one emotion hardest to fight against is a longing in all things for the past. After the others have gone to bed, I pass the time on a long autumn’s night by putting in order whatever belongings are at hand. As I tear up scraps of old correspondence I should prefer not to leave behind, I sometimes find among them samples of the calligraphy of a friend who has died, or pictures he drew for his own amusement, and I feel exactly as I did at the time. Even with letters written by friends who are still alive I try, when it has been long since we met, to remember the circumstances, the year. What a moving experience that is! It is sad to think that a man’s familiar possessions, indifferent to his death, should remain unaltered long after he is gone.

Once when the retired emperor's courtiers were playing at riddles in the Daigakuji palace, the physician Tadamori joined them. The Chamberlain and Major Counselor Kinakira posed the riddle: "What is it, Tadamori, that doesn't seem to be Japanese?" Somebody gave the answer: "Kara-heiji—a metal wine jug." The other all joined in the laugh, but Tadamori angrily stalked out.

The words "fixed complement" are used not only about priests at the various temples but in the Engishiki for female officials of lower rank. The words must have been a common designation for all officials whose numbers were fixed.

You should never put the new antlers of a deer to your nose and smell them. They have little insects that crawl into the nose and devour the brain.

If we pick up a brush, we feel like writing; if we hold a musical instrument in our hands, we wish to play music. Lifting a wine cup makes us crave saké; taking up dice, we should like to play backgammon. The mind invariably reacts in this way to any stimulus. That is why we should not indulge even casually in improper amusements.

Even a perfunctory glance at one verse of some holy writing will somehow make us notice also the text that precedes and follows; it may happen then, quite suddenly, that we mend our errors of many years. Suppose we had not at that moment opened the sacred text, would we have realized our mistakes? This is a case of accidental contact producing a beneficial result. Though our hearts may not be in the least impelled by faith, if we sit before the Buddha, rosary in hand, and take up a sutra, we may (even in our indolence) be accumulating merit through the act itself; though our mind may be inattentive, if we st in meditation on a rope seat, we may enter a state of calm and concentration, without even being aware of it.

Phenomenon and essence are fundamentally one. If the outward form is not at variance with the truth, an inward realization is certain to develop. We should not deny that is is true faith; we should respect and honor a conformity to truth.

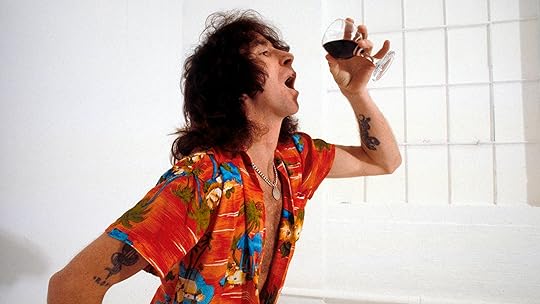

“People say I ain’t doin’ much / doin’ nothing means a lot to me!”Dit citaat van de Australische wijsgeer Bon Scott (1946-1980) prijkte in mijn middelbare schooltijd in sierlijke gekrulde letters op mijn mooiste schoolkaft. 't Is maar om te zeggen: ik ben al lang met niets bezig. Later ontdekte ik in dada en zen nog meer schoonheid en kunst van het niets.

“Je moet een pas aangegroeid hertengewei nooit tegen je neus houden. Er zitten kleine beestjes in die door je neusgaten naar binnen kruipen en je hersenen opvreten.”Of ook:

“Wie hooggeboren is, kan maar beter geen kinderen hebben en voor wie laaggeboren is geldt dat nog meer.”Maar daar ben ik het natuurlijk niet mee eens! That would be 'a touch too much'!