What do you think?

Rate this book

174 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1952

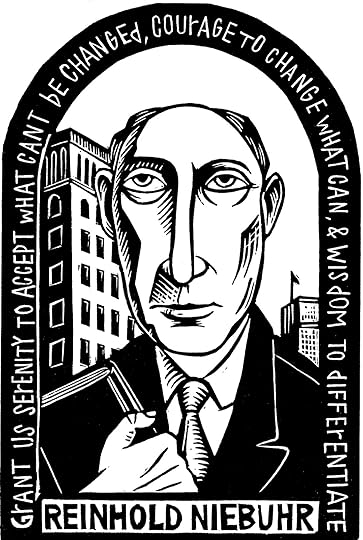

God grant me the serenityMuch like his better-known prayer, this book recommends a pragmatic approach to foreign policy. Niebuhr is eminently quotable and I found myself often highlighting passages in the book.

to accept the things I cannot change;

courage to change the things I can;

and wisdom to know the difference.

Pure tragedy elicits tears of admiration and pity for the hero who is willing to brave death or incur guilt for the sake of some great good. Irony however prompts some laughter and a nod of comprehension beyond the laughter; for irony involves comic absurdities which cease to be altogether absurd when fully understood.And what is this ironic situation?

Our age is involved in irony because so many dreams of our nation have been so cruelly refuted by history. Our dreams of a pure virtue are dissolved in a situation in which it is possible to exercise the virtue of responsibility toward a community of nations only by courting the prospective guilt of the atomic bomb.Against this backdrop, Niebuhr recognizes that great power comes with equally great temptation. The temptation to dominate others, especially smaller nations. And probably most important, the temptation to equate power with virtue…

Modern man’s confidence in his virtue caused an equally unequivocal rejection of the Christian idea of the ambiguity of human virtue.Or,

Power always thinks it has a great soul and vast views beyond the comprehension of the weak; and that it is doing God’s service when it is violating all His laws. (Letter from John Adams to Thomas Jefferson)Niebuhr’s ability to highlight these temptations, and warn us to identify and fight against them, is one of the main values of this book.