I first discovered The Empire Striketh Back in 2015, on one of those muggy, monsoon afternoons in Kolkata when the city smells of drenched history and secondhand books. I wasn’t looking for it.

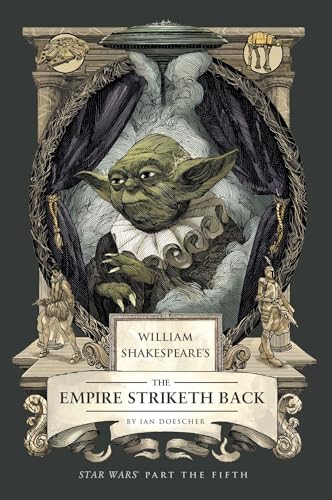

In fact, I was just wandering through an old shop off College Street, nursing a heartbreak and escaping lesson plans about Othello. Then it caught my eye—Darth Vader in an Elizabethan ruff on the cover, lightsaber aloft like a royal sceptre.

The absurdity thrilled me. I opened it, read Vader’s soliloquy in blank verse, and grinned like a student discovering that their favourite pop star could quote Milton. That day, I left with the book clutched tight, as if it held not just parody, but promise.

Ian Doescher’s The Empire Striketh Back is no gimmick. It is an audacious, reverent collision of two canons—George Lucas’s space opera and William Shakespeare’s dramaturgy—bound together in iambic pentameter and Elizabethan dramaturgical wit.

It is not just Star Wars in verse. It is Star Wars as if Hamlet, Falstaff, and Lear had all crowded into Cloud City and debated fate, loyalty, and the dark side. Doescher takes the second film of the original trilogy and reframes it with all the tools of the Bard—soliloquies, choruses, asides, nobles in turmoil, jesters with insight, and villains with poetry in their grief.

Reading it, I was stunned at how naturally the form fit the function. Yoda’s cryptic syntax suddenly sounded like a woodland mystic from A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Leia’s pain at Han’s capture rang with the fierce dignity of Lady Macbeth. Even the AT-AT Walkers on Hoth have a kind of tragicomic pomp, like armored elephants from Titus Andronicus. Here is Vader, cold and commanding:

“My purpose plain is to ensnare the son

Of Skywalker, and turn him to the dark.”

And here is Yoda, his riddles now full-on Shakespearean koan:

“For things of worth must needs with effort won,

And Jedi path is not the easy one.”

This isn't mere mimicry. It’s a full theatrical transposition. Every character is deepened through verse. Luke’s torment about his father becomes an existential reckoning. Han Solo, ever the sarcastic rogue, now struts like Mercutio in space boots. Even Chewbacca gets his moment—roaring in stage direction, his growl subtitled with tragic resonance. And R2-D2, that mechanical jester, suddenly turns meta, addressing the audience with rhymed commentary, as if he were both fool and chorus.

I remember reading it aloud in my room at night, doing all the voices. Somewhere between Boba Fett’s cold logic and Lando Calrissian’s velvet betrayals, I stopped laughing and simply listened. The language—rhythmic, rich, often ridiculous—had begun to sing.

And I thought, perhaps Shakespeare would have loved this. Not just for the poetic play, but for the sheer theatricality of it. The masks, the betrayals, the longing—this was classic tragedy. Just with lightsabers.

What made it more poignant was the timing. I was teaching Hamlet that term, and grappling with my own father’s illness. Vader’s anguish, Luke’s reckoning, their fatal symmetry—suddenly hit closer than I had expected. Doescher gave them Shakespeare’s voice, yes, but the emotions were my own. I remember reading:

“What light through yonder Death Star breaks?”

and both chuckling and choking up.

Even now, a decade later, the book lives in me like a good performance. It reminds me that Shakespeare is not a museum piece. He’s a time-traveler. That blank verse can hold both the grief of a Danish prince and the groan of a dying Jedi. That narrative forms are malleable. That literature, at its best, isn’t about reverence—it’s about remix. Imagination. Fusion.

Doescher’s The Empire Striketh Back is a love letter to fandoms—both Shakespearean and galactic. It's proof that a writer can be both a nerd and a poet, a dramatist and a dreamer. In its pages, the Force meets fate, sabers meet soliloquy, and somewhere in the night sky of the mind, an X-Wing flies across the Globe Theatre.

When I finished reading it in 2015, I closed the book softly and whispered, like an exhale across centuries: “May the pentameter be with thee—always.”