What do you think?

Rate this book

Kindle Edition

First published November 1, 2007

One day Orlov stuffed himself with mashed peas and died. Krylov, having heard the news, also died. And Spiridonov died regardless. And Spiridonov’s wife fell from the cupboard and also died. And the Spiridonov children drowned in a pond. Spiridonov’s grandmother took to the bottle and wandered the highways. And Mikhailov stopped combing his hair and came down with mange. And Kruglov sketched a lady holding a whip and went mad. And Perekhryostov received four hundred rubles wired over the telegraph and was so Uppity about it that he was forced to leave his job.

All good people but they don’t know how to hold their ground.

In the courtyard stands an old woman holding in her hands a clock. I walk past the old woman, stop and ask her: “What time is it?”

“Take a look,” says the old woman.

I look and see that the clock has no hands.

“There are no hands there,” I say.

The old woman looks at the clock face and says to me:

“It’s quarter to three.”

“So, that’s how it is? Thanks very much,” I say and leave.

I once saw a fly and a bedbug get into a fight. It was so frightening that I ran out into the street and ran as far as I could.

from The Werld:Then I realized that since before there was somewhere to look – there had been a world around me. And now it’s gone. There’s only me.

And then I realized that I am the world.

But the world – is not me.

Although at the same time I am the world.

But the world’s not me.

And I’m the world.

But the world’s not me.

And I’m the world.

But the world’s not me.

And I’m the world.

And after that I didn’t think anything more.

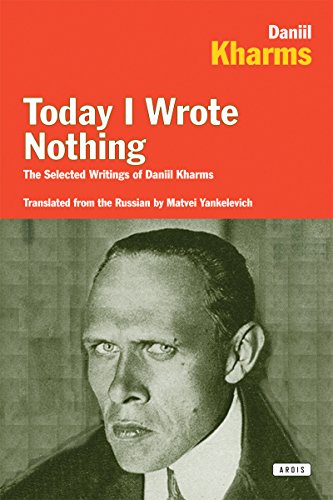

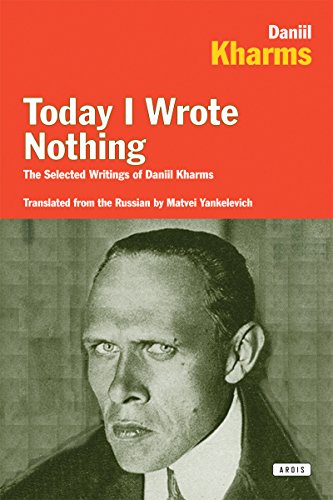

This guy is funny. This guy is frightening. He’s ultra-serious and slapstick hilarious. The world portrayed in his writings is like a world reduced to a Beckett stage-set – a bed, a cucumber, a clock – in an otherwise whited-out world, and with this minimalism a metaphysical cosmos of violent absurdity and eccentricity, strobe-lit with transcendent flashes, is created.

His intentions were in fact to write short intense works, or "Incidences" as he preferred, that isolate absurd or violent events, or events so mundane as to be meaningless, and through this isolation to create a “flash” of transcendent vision and a moment of being beyond earthly constraints.

And he knew constraints.

He was a second generation Soviet avant-gardist, which marginalized him by definition, and of course he was thoroughly uncompromising and a thoroughgoing dandy and purposeful eccentric (he actually developed a verbal/physical tic that was a literally embodied example of his fractured aesthetics). All this eventually led to his imprisonment on suspicion of anti-soviet activities. He died of starvation in prison in 1942 at the age of 37.

But though his work directly reflects his “condition” in the early Soviet Union, it by no means is dependent on that condition to give it meaning. This is literary experimentation of the highest universal order, and once the barbed surface of its seeming pointlessness and absurdity is broke, profound (though elusive) meanings spill out along with its more immediate literary pleasures.AN INCIDENT INVOLVING PETRAKOV

So, once Petrakov wanted to go to sleep but, lying down, missed the bed. He hit the floor so hard he lay there unable to get up.

So Petrakov mustered his remaining strength and got on his hands and knees. But his strength abandoned him and he fell on his stomach again, and he just lies there.

Petrakov lay on the floor about five hours. At first he just lay there, but then he fell asleep.

Sleep refreshed Petrakov’s strength. He woke up invigorated, got up, walked around the room and cautiously lay down on the bed. “Well,” he thought, “now I’ll get some sleep.” But now he’s not feeling very sleepy. So Petrakov keeps turning in his bed and can’t fall asleep.

And that’s it, more or less.

Гость на коне

Конь степной

бежит устало,

пена каплет с конских губ.

Гость ночной

тебя не стало,

вдруг исчез ты на бегу.

Вечер был.

Не помню твердо,

было все черно и гордо.

Я забыл

существованье

слов, зверей, воды и звёзд.

Вечер был на расстояньи

от меня на много верст.

Я услышал конский топот

и не понял этот шопот,

я решил, что это опыт

превращения предмета

из железа в слово, в ропот,

в сон, в несчастье, в каплю света.

Дверь открылась,

входит гость.

Боль мою пронзила

кость.

Человек из человека

наклоняется ко мне,

на меня глядит как эхо,

он с медалью на спине.

Он обратною рукою

показал мне — над рекою

рыба бегала во мгле,

отражаясь как в стекле.

Я услышал, дверь и шкап

сказали ясно:

конский храп.

Я сидел и я пошёл

как растен��е на стол,

как понятье неживое,

как пушинка

или жук,

на собранье мировое

насекомых и наук,

гор и леса,

скал и беса,

птиц и ночи,

слов и дня.

Гость я рад,

я счастлив очень,

я увидел край коня.

Конь был гладок,

без загадок,

прост и ясен как ручей.

Конь бил гривой

торопливой,

говорил —

я съел бы щей.

Я собранья председатель,

я на сборище пришёл.

— Научи меня Создатель.

Бог ответил: хорошо,

Повернулся

боком конь,

и я взглянул

в его ладонь.

Он был нестрашный.

Я решил,

я согрешил,

значит, Бог меня лишил

воли, тела и ума.

Ко мне вернулся день вчерашний.

В кипятке

была зима,

в ручейке

была тюрьма,

был в цветке

болезней сбор,

был в жуке

ненужный спор.

Ни в чём я не увидел смысла.

Бог Ты может быть отсутствуешь?

Несчастье.

Нет я всё увидел сразу,

поднял дня немую вазу,

я сказал смешную фразу —

чудо любит пятки греть.

Свет возник,

слова возникли,

мир поник,

орлы притихли.

Человек стал бес

и покуда

будто чудо

через час исчез.

Я забыл существованье,

я созерцал

вновь

расстоянье.

1931–1934

Некий инженер задался целью выстроить поперёк Петербурга огромную кирпичную стену. Он обдумывает, как это совершить, не спит ночами и рассуждает. Постепенно образуется кружок мыслителей-инженеров и вырабатывается план постройки стены. Стену решено строить ночью, да так, чтобы в одну ночь всё и построить, чтобы она явилась всем сюрпризом. Созываются рабочие. Идёт распределение. Городские власти отводятся в сторону, и наконец настаёт ночь, когда эта стена должна быть построена. О постройке стены известно только четырём человекам. Рабочие и инженеры получают точное распоряжение, где кому встать и что сделать. Благодаря точному расчёту, стену удаётся выстроить в одну ночь. На другой день в Петербурге переполох. И сам изобретатель стены в унынии. На что эту стену применить, он и сам не знал.

Даниил Хармс - 1930

A certain engineer has made up his mind to build a huge brick wall across Petersburg. He considers how to accomplish this, doesn't sleep for nights cogitating it. Gradually a group of engineering planners is formed and a plan for the construction of the wall is elaborated. It was decided to build the wall at night, indeed, to build the whole thing in one night, so that it would appear as a surprise to everyone. Workers are summoned. The organisation is under way. The city authorities are sidelined and finally the night arrives when this wall is to be built. The building of the wall is known only to four men. The workers and engineers receive exact instructions as to whom to place where and what to do. Thanks to exact calculation, they succeed in putting up the wall in a single night. On the following day there is consternation in Petersburg. And the inventor of the wall is himself dejected. To what use this wall was to be put, he himself did not know.

Daniil Kharms (1930)

Guest on a Horse

Horse of the steppe

runs tired,

froth drips down the equine lip.

Guest of the night,

you expired,

you suddenly vanished mid-gallop.

There was evening.

I can’t remember,

everything was black and proud.

I forgot

the existence

of words, beasts, water, and stars.

Evening was at a distance

from me, of many miles.

I heard the hoofbeat of a horse,

I didn’t understand this hoarse

message, I thought it was a test

run of an object’s transformation

from iron into word, into noise,

dream, drop of light, disaster, loss.

The door opened,

the guest entered alone.

Pain pierced

my bone.

A man bends my way

out of a man,

stares at me like an echo,

has a medal pinned on his back.

He showed me with his inverse arm:

above the river in the dark

a fish upon its legs did pass,

reflected as if in a glass.

I heard the wardrobe and the door

clearly say:

a horse’s snort.

I was sitting and I went

like a plant onto a table,

like a concept void of life,

like a feather

or a beetle

to the universal congress

of all sciences and insects,

mountains, forests,

cliffs and demons,

birds and night,

words and day.

I am glad, O guest,

so happy

that I glimpsed the edge of the horse.

It was smooth,

without riddles,

clean and clear as a brook.

It shook its mane,

a little strained,

it said,

“I’d like a bit of soup.”

I was the chairman of the congress,

I had come to the assembly.

“Educate me, O Creator,”

and God answered, “very well.”

Sideways turned

the horse and

I looked

into its hand.

The horse wasn’t frightening at all.

I decided

I had sinned,

meaning, God deprived me

of body, mind, and will.

Yesterday came back to me.

In boiling water

there was winter,

in the stream

there was a prison,

in the flower

diseases acute,

in the beetle

a useless dispute.

I didn’t see meaning in anything.

God, maybe you’re absent?

What a disaster.

No, I saw it all at once,

I picked up the day’s mute vase,

I spoke out a funny phrase:

miracle loves to warm its heels.

Light appeared,

words appeared,

the world was spent,

the eagles fell silent.

The man became a demon here

in the meantime

like a miracle

in an hour disappeared.

I forgot about existence,

I again

contemplated

the distance.

1931–1934

"They say all the good babes are wide-bottomed. Oh, I just love big-bosomed babes. I like the way they smell.” Saying this he began to grow taller and, reaching the ceiling, he fell apart into a thousand little spheres. [‘How One Man Fell To Pieces’, page 231.]

Poisoning children is cruel. But something has to be done about them!

What’s all the fuss about flowers? It smells way better between a woman’s legs. That’s nature for you, and that’s why no-one dares find my words distasteful. [Untitled, page 252]