What do you think?

Rate this book

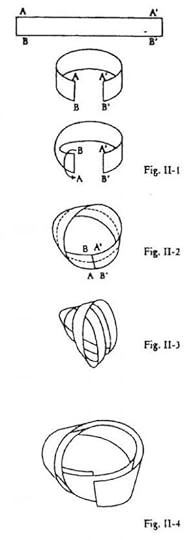

In Fashionable Nonsense, Alan Sokal, the author of the hoax, and Jean Bricmont contend that abuse of science is rampant in postmodernist circles, both in the form of inaccurate and pretentious invocation of scientific and mathematical terminology and in the more insidious form of epistemic relativism. When Sokal and Bricmont expose Jacques Lacan's ignorant misuse of topology, or Julia Kristeva's of set theory, or Luce Irigaray's of fluid mechanics, or Jean Baudrillard's of non-Euclidean geometry, they are on safe ground; it is all too clear that these virtuosi are babbling.

Their discussion of epistemic relativism--roughly, the idea that scientific and mathematical theories are mere "narrations" or social constructions--is less convincing, however, in part because epistemic relativism is not as intrinsically silly as, say, Regis Debray's maunderings about Gödel, and in part because the authors' own grasp of the philosophy of science frequently verges on the naive. Nevertheless, Sokal and Bricmont are to be commended for their spirited resistance to postmodernity's failure to appreciate science for what it is. --Glenn Branch

306 pages, Paperback

First published October 1, 1997

"In some cases, Baudrillard’s invocation of scientific concepts is clearly metaphorical. For example, he wrote about the Gulf War as follows:

What is most extraordinary is that the two hypotheses, the apocalypse of real time and pure war along with the triumph of the virtual over the real, are realised at the same time, in the same space-time, each in implacable pursuit of the other. It is a sign that the space of the event has become a hyperspace with multiple refractivity, and that the space of war has become definitively non-Euclidean. (Baudrillard 1995,

p. 50, italics in the original)

There seems to be a tradition of using technical mathematical notions out of context."