What do you think?

Rate this book

320 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 2015

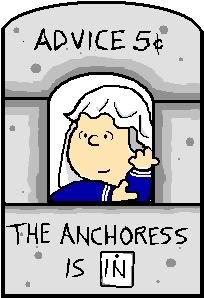

England, 1255: Sarah is only seventeen when she chooses to become an anchoress, a holy woman much like the one who taught Saint Hildegard of Bingen, shut away in a small cell, measuring seven by nine paces, at the side of the village church. Fleeing the grief of losing a much-loved sister in childbirth as well as pressure to marry, she decides to renounce the world—with all its dangers, desires, and temptations—and commit herself to a life of prayer. But it soon becomes clear that even the thick, unforgiving walls of Sarah’s cell cannot keep the outside world away, and her body and soul are still in great danger.I didn't know much about the anchoress life, and I feel like I learned a lot about that from this book. Church mystics who withdraw and have ecstatic experiences are pretty fascinating, and I think the author felt the same way. I do wish the writing had varied a bit more - in around 200 pages the word "throb" was used 16 times, to such excess that I noticed it and went looking. There are some questions raised (in my mind) of the line between mental illness and spiritual devotion/ecstasy. I thought the connection of the church to the village was interesting too. So much depends on how a person survives, and that makes it more complicated than a person shutting herself up in a room.