'"Beyond God", said Hillier, "lies the concept of God. In the concept of God lies the concept of anti-God. Ultimate reality is a dualism or a game for two players. We - people like me and my counterparts on the other side - we reflect that game''.'

I wonder which spy novel, of the many that I have read, ever said such a profound and revealing thing about the nasty little game of espionage and deception that spies and traitors are condemned to play all their lives. It is moments like these in Anthony Burgess' 'Tremor Of Intent' that sound and seem as if he really, as his intention was, showed everybody else how to write a spy novel.

Dennis Hillier is a MI6 man about to retire. His last job is to bring back English scientist Roper, who betrayed his country and has already disappeared behind the Iron Curtain. So far, as this scathingly bitter and cynical tale begins, we feel that we are in a territory of cloaks and daggers bleaker and more nihilistic than that of John Le Carre and Graham Greene. We are taken through Hillier's memories of Roper enlisting for the Second World War while debating religion and returning transformed and literally shell-shocked by the brutality that resulted from the global conflict. Is that not reason sufficient for a man to betray his own ideology and country?

Out of nowhere, there comes a pre-adolescent boy who knows an awful lot about everything, including identifying spies. There is his sister, a nubile nymphet straight out of Nabokov, who stirs sinful desire into the loins of our man Hillier, on a ship bound for the Black Sea coast. And while they are introduced as comic asides in the plot initially, Burgess then makes them- these two kids- willful accomplices to our spy when he is caught in a big fix.

And then you think- is this book for real?

But then, that is the point of it all. The Wikipedia page of 'Tremor Of Intent' will inform you that the novel confused critics and readers because so seamlessly does Burgess flit from a serious, high-brow tone of fiction to low-brow sleaze and farce that the difference vanishes literally. You walk into it expecting a sobering meditation on the life of spy and what death means to him (the subtitle suggests that) and just halfway through this expected pitch, the writer pulls the rug beneath your feet, plunging you into an unashamed orgy of gluttony, gags and grinding between the sheets.

Burgess' original intentions were to spoof both the seriousness of Le Carre and the sizzling glamour of Ian Fleming and boy, does he nail it with such fastidious brilliance and inventive wordplay that the reader might be taken aback but his jaw will still be lying on the floor, smashed open. Sample this for instance:

'Perhaps all of us who are engaged in this sort of work - international intrigue, espionage, scarlet pimpernellianism. hired assassination - seek something deeper than what most people term life, meaning a pattern of simple gratifications'.

That masterstroke of a sentence is a jab at both George Smiley and James Bond. But the audacity elsewhere is pure Burgess.

'Kraarkh kraarkh. Their memento mori tucked away, the voyagers tucked in. The Polyolbion dodged among the Cyclades. Kraarkh.'

As I said, this is a crazed, fever dream of a novel. There are parts of it soaked in bitter darkness and self-loathing, where Burgess hurtles us relentlessly into the brutal reality of being caught in the bigger game of espionage and intrigue that leaves men like burned out shells. Then again, there are parts so comically nonsensical yet so spectacularly surreal that they stun you with their outrageous wit even when it all leads nowhere, even as the main plot - of Hillier trying to finish the last job honorably despite his own weaknesses for vice and women thwarting his plans - becomes almost recklessly ridden with plot-holes. No, it is not lazy writing. It's just crazy writing.

There is an assassination that goes kaput, there is the quintessential game of cards replaced by a game of literal eating (and mind you, the delicacies served up are truly delectable) and then, there is Miss Devi.

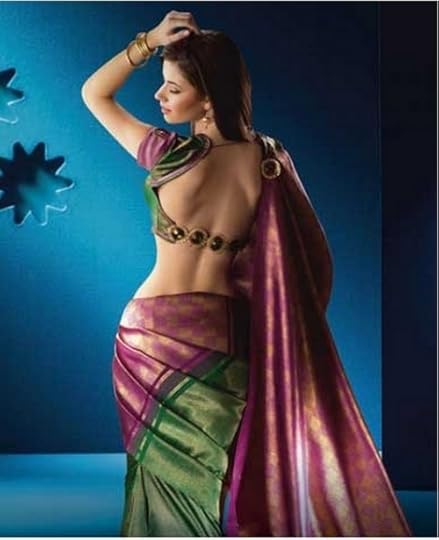

Oh yes, Miss Devi. Burgess packs in more sex than you would find in all the Fleming books put together but here too, his touch is in breaking the stereotype. Miss Devi, the disarmingly deceptive, devilishly dusky and intelligent seductress of this book, is no gorgeous and heroic Caucasian as Fleming likes his idea of a girl but rather, as Hillier himself muses, a 'door to another world'.

Is it the best spy novel ever? No, not really. 'The Human Factor' won that title in my book. But long before Austin Powers thought of mocking secret agents, we had Burgess and he was a lot more than just a brilliant comic writer.

I sign off by promising, for the virgins, that sensational scene of lovemaking in the middle of the book that really reveals those unearthly and carnal pleasures that this femme fatale hides and then unveils. For Miss Devi, that goddess of lust incarnate herself, I recommend this book wholeheartedly.