What do you think?

Rate this book

408 pages, Hardcover

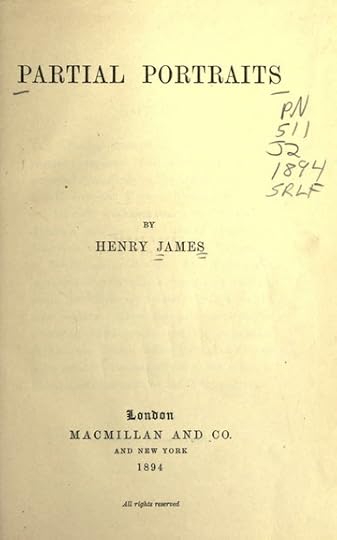

First published January 1, 1888

He was not all there, as the phrase is; he had something behind, in reserve. It was Russia of course, in large measure; and especially before the spectacle of what is going on there today, that was a large quantity.