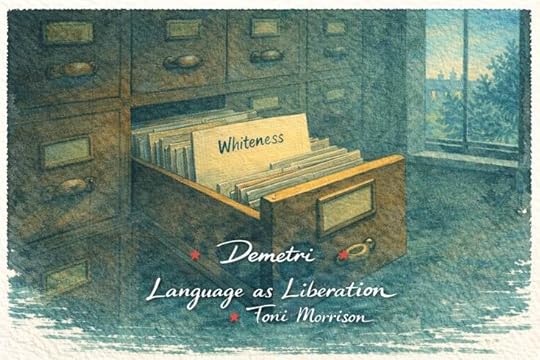

This book presents the raw material that formed her earlier book: "Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination." Both grow out of the class she taught at Princeton and illustrate her analysis of the Africanist presence in American literature. She shows how white authors constructed the Africanist character to bolster whiteness and shape and control both what it means to be black and/or white or to comment on this practice. Importantly, her points are grounded firmly in the text and how it functions without passing judgment on the work or the authors.

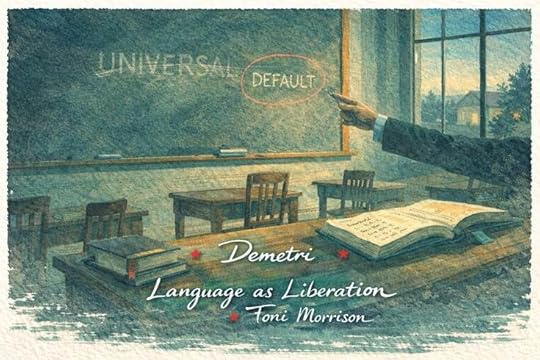

To address how race is at the core of the American narrative, she asks, "How could one speak of profit, of economy, of labor, of progress, of suffragism, or Christianity, of the frontier, of the formation of new states, the acquisition of new lands, of education, of transportation--freight and passengers--neighborhoods, quarters, the military--practically anything a new nation concerns itself with--without having as a referent, at the heart of the discourse or defining its edges, the presence of Africans and/or their descendants?" One would think such a question is undeniable, but in looking around society today, one would see many attempts to not only deny the question but also prevent its being asked. However, we must disentangle ourselves from false narratives, especially ones that manufacture an "other" to bolster power structures and establish identities (both of the "me" and "not me). She cites James A. Snead, who in addressing the works of William Faulkner, wrote, "A community of speakers and listeners solidifies its own corporate identify and...authority by repeating a series of highly figured stories that approximate 'reality' even if the 'real' narrative depends upon rampant misinformation or multiple omissions." Such a statement applies to past, present, and likely future, where much of public perceptions are shaped through narratives. In essence, authority disseminates information (in the form of narrative) to mold the perceptions of those under said authority, leading these perceptions to become reality. These narratives are the lens through which people view reality.

Ultimately, this book gifted me with the somewhat vicarious experience of being a student in Morrison's class, listening to her guide me through texts as she cleaved to the heart of how she saw them functioning. Additionally, it reiterated Morrison's brilliance and importance to American literature. I will note, as my initial statement suggests, that the book does have a rawness to it, as it was not necessarily built for publication (again, as noted, that would be the "Playing in the Dark" book).