What do you think?

Rate this book

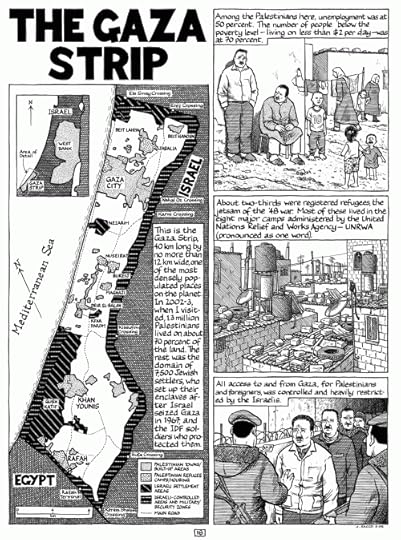

Rafah, a town at the bottommost tip of the Gaza Strip, is a squalid place. Raw concrete buildings front trash-strewn alleys. The narrow streets are crowded with young children and unemployed men. On the border with Egypt, swaths of Rafah have been bulldozed to rubble. Rafah is today and has always been a notorious flashpoint in this bitterest of conflicts.

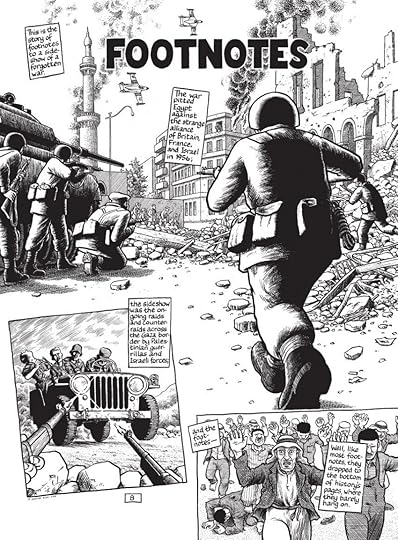

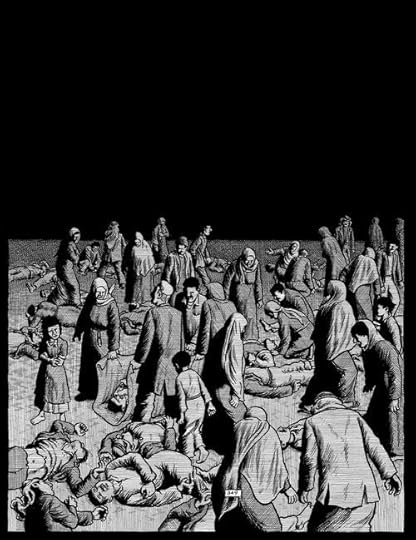

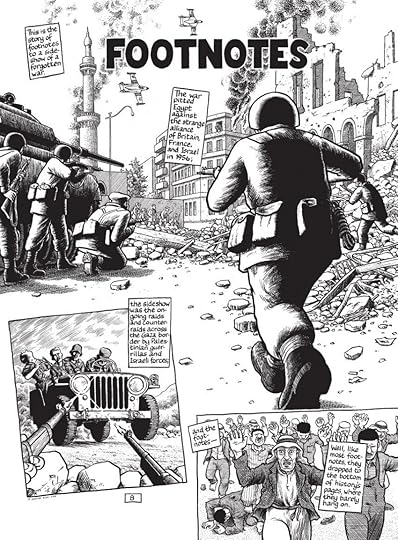

Buried deep in the archives is one bloody incident, in 1956, that left 111 Palestinians dead, shot by Israeli soldiers. Seemingly a footnote to a long history of killing, that day in Rafah—cold-blooded massacre or dreadful mistake—reveals the competing truths that have come to define an intractable war. In a quest to get to the heart of what happened, Joe Sacco immerses himself in daily life of Rafah and the neighboring town of Khan Younis, uncovering Gaza past and present. Spanning fifty years, moving fluidly between one war and the next, alive with the voices of fugitives and schoolchildren, widows and sheikhs, Footnotes in Gaza captures the essence of a tragedy.

As in Palestine and Safe Area Goražde, Sacco’s unique visual journalism has rendered a contested landscape in brilliant, meticulous detail. Footnotes in Gaza, his most ambitious work to date, transforms a critical conflict of our age into an intimate and immediate experience.

400 pages, Unknown Binding

First published January 1, 2009

The son shall not bear the iniquity of the father, neither shall the father bear the iniquity of the son…Joe Sacco, to quote The New York Review of Books, “is legitimately unique.” He is a journalist, cartoonist, and historian. And he is, based on the books of his I’ve read, one hell of a Mensch. He focuses on the stories few journalists are willing to investigate. Footnotes in Gaza is his masterpiece. It tells the story of a little-known and mostly forgotten historical episode: the massacres of Palestinians in Khan Younis and Rafah, two cities in the extreme southern part of the Gaza Strip, that took place in 1956. Forty-seven years after the events, in 2003, Sacco went to Gaza to find and interview people who lived at that time when, as he acknowledges throughout his book, memories were fragile and fallible. He examined historical records. He intertwined his account with the current events of 2003, when the U.S. was preparing to invade Iraq and Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) were destroying houses in Rafah, which is on the Egyptian border, because of their suspected ties to terrorist activity. His cartoonist’s eye creates stunning images that make up for the lack of a visual record of the events he describes. Although his vantage point is, for the most part, from within Gaza, only the most cynical, ideological, and narrow-minded of critics could claim that Sacco’s telling of the story and conclusions are not judicious.

~ Ezekiel 18:20

“When the facts come home to roost, let us try at least to make them welcome…to give due account for the sake of freedom to the best in men and to the worst.”

~ Hannah Arendt

But I believe there'll come a day when the lion and the lamb

Will lie down in peace together in Jerusalem

And there'll be no barricades then

There'll be no wire or walls

And we can wash all this blood from our hands

And all this hatred from our souls

And I believe that on that day all the children of Abraham

Will lay down their swords forever in Jerusalem

~ Steve Earle, Jerusalem

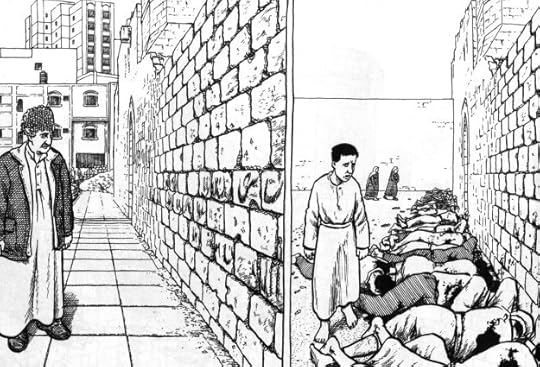

The town of Khan Yunis and the Agency’s camp adjacent thereto were occupied by Israel troops on the morning of 3 November…The Israel authorities state that there was resistance to their occupation and that the Palestinian refugees formed part of that resistance. On the other hand, the refugees state that all resistance had ceased at the time of the incident and that many unarmed citizens were killed as the Israel troops went through the town and camp, seeking men in possession of arms. The exact number of dead and wounded are not known, but…trustworthy lists…of persons allegedly killed…[are] 275 individuals…In conversations with people living at that time, Sacco describes how the men of Khan Younis were gathered together and lined up facing a wall. Indiscriminate shots were fired both at them and over their heads with the dead and wounded falling where they stood. Sacco himself acknowledges, “The U.N. report presents to incompatible versions of the Khan Younis ‘incident,’ and so in this case, as in many others, history-by-document drops us into a muddied soup of ‘on the other hands’ and ‘possibilities’ seasoned, perhaps, with a few ‘probables.’ But clearly the refugees’ claim in the U.N. report dovetails with the eyewitness testimony Abed and I gathered many nears later. Namely: the fighting had stopped; the men were unarmed; they did not resist.”

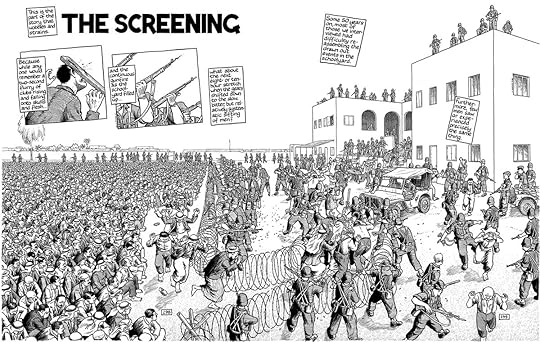

On 12 November, a serious incident occurred in the Agency’s camp at Rafah. Both the Israel authorities and UNRWA’s other sources of information agree that a number of refugees were killed and wounded at that time by occupying forces. A difference of opinion exists as to how the incident happened and as to the numbers of killed and wounded. It is agreed, however, that the incident occurred during a screening operation conducted by Israel forces…The facts appear to be as follows: Rafah is a very large camp (more than 32,000 refugees) and the loudspeaker vans which called upon the men to gather at designated screening points were not heard by some of the refugee population…sufficient time was not allowed for men to walk to the screening points…In the confusion, a large number of refugees ran toward the screening points for fear of being late, and some Israel soldiers apparently panicked and opened fire on this running crowd…sources consider[ed] trustworthy lists…persons allegedly killed…numbering 111…As with the Khan Younis incident, Sacco sorts through some conflicting accounts to conclude that some memories seem to have invented incidents, especially immediately after the shootings, and distorted time sequences.

Here, again, Sacco gives space to long-ignored Palestinian voices and memories, trying to build a record of what really happened. It is a difficult mission in a place like Gaza, where – during the Second Intifada when Sacco conducted his research, and otherwise – violence, arbitrary killings, and IDF incursions have long become the norm. Indeed, a journalist could

file last month's story – or last year's, for that matter – and who'd know the difference?The past and the present often collapse into each other in Gaza, but Sacco persists in drawing out – with the help of his Palestinian translator and, equally importantly, the local historian who has already created an Arabic-language account of the incidents – a clearer picture of this painful footnote from the eyewitnesses who survived it. The result is a painful, heartbreaking book, perhaps more destabilising than the previous one, and just as unabating in its narrativisation of the unrelenting violence in Gaza past and present.