What do you think?

Rate this book

320 pages, Hardcover

First published April 8, 2015

To be fair, "the demilitarization of landscapes" (introduction, p.13) is a large topic, and the nine essays within Edwin A. Martini's edited collection provide a slice, but the book is not a compelling read. Part of the problem is the editor's preference for what he calls "the detached perspective" (intro., p.5), which makes for some bloodless writing, in the policy vein, as opposed to the "resistance school," (pp.4-6) writings that do not shy away from value judgments about U.S. militarism and imperialism. As a result, the latter is sorely underrepresented and instead, on the whole, this collection seems to strive for what might be called a veneer of objectivity, an academic tone of detachment that tends to reinforce the status quo. Perhaps this even bleeds into providing apologia for past U.S. military mistakes, or the current refusal to own up to environmental disasters caused, both at home and abroad, by U.S. military forces and/or "militarized landscapes" incidental to U.S. bases. For example, Chapter 2 relies so much on official sources and the writing is so dry that likely few readers will make it any further into the book. Yet the introduction promises discussion of "charges of ecocide" (p.14) made against the U.S. military. Instead we get a tendentious argument that the U.S. military is capable of acknowledging "nature's integral role" (intro, p.8) --even as that same organization went about blowing up atolls in the Pacific with its nuclear bombs, pock-marking the sea-bed floor in the process, and/or creating artificial aurora in the upper atmosphere, with radioactive particles raining down (mentioned in Chapter 4).

Chapter 1, by Brandon C. Davis, addresses the illegitimacy of the land acquisitions made by the U.S. military using "national security" (p.20) as the excuse. An "unbound" (p.21) system of executive withdrawals from the commons, for the sake of creating military lands, "gradually became formalized as World War II ended" even though originally intended only as a "temporary wartime emergency" (p.21). How unbounded was it? There was an "800 percent increase in military real property holding within three years of the outbreak of World War II." (p.35) "From the start of World War II to the mid-1950s...nearly twenty million acres of 'jealously guarded' public land was rapidly withdrawn from the public domain and put under the control of military interests." (p.29). And thereafter, "[b]etween 1954 and 1955 alone, the Defense Department made requests amounting to nearly thirteen million additional acres of public land." (p.31) The WWII-ColdWar era assertion of executive authority (think 'imperial presidency') was double -dged: Not only was the presidency construed to have a constitutionally-granted prerogative to defend the nation, involving autocratic powers albeit temporary and applicable only in times of emergency --with a "return to constitutional normalcy" (p.21) built in to such emergency powers-- but what is more, and in a novel spin on "R2P" (again, not an acronym used in this volume), the president also was understood to have a 'responsibility to protect' public lands, and this teponsibility was both independent of emergency and time limits. On the one hand, without any statutory authority behind it, military land-grabs under presidential decree "have disempowered and dispossessed local peoples from land and resources" (p.23) to which they would otherwise enjoy some customary claim to benefit from, as public domain or as private lands free from applications of eminent domain, or emergency powers. (Although the details of public land users with long-standing interests in the land are not covered here, see for example, the discussion in Montrie, A People's History of Environmentalism in the U.S., chapters 1 & 2, or Steinberg, Down to Earth: Nature's Role in American History, chapters 4, 5 & 7) On the other hand, the purported "stewardship duty of the executive" (p.23) has been subject to judicial review, using the public interest as a crucial touchstone. Although a 1909 ruling created a dangerous precedent legitimizing presidential land-grabs, creating an implied power for the executive branch to define impoundment of property in the public interest (aka 'national interest', or 'national security'), fortunately Congress stepped in with a statute in 1910 limiting executive powers in this regard, restricting presidential ambitions to lay claim unchecked to lands for the purposes of the U.S. military, creating specific delegated powers to do so only, and reasserting public land laws (p.26). It is supposed that 'necessity knows no law' but the presidency's emergency powers were limited even during WWII, and emergency impoundment of land for war purposes was subject to a sunset clause; demilitarization of the land was to occur just 6 months after the end of that conflict, by executive order of FDR (pp.29-30). One is left to conclude that the newfangled doctrine creating a responsibility to protect public lands in the public interest, or according to national security as defined by the executive, is really a creeping authoritarianism, contrary to the spirit of the law. The danger of arbitrary enclosures of land by the executive branch was a concern at least as early as the late 19th century (p.27), the idea of a president creating permanent reservations being contrary to the will of Congress. Under Truman, the illegitimate enclosures were allowed to continue, the military essentially squatting on lands without any statutory authority ("became routine", p.31). In the vacuum, there being no statutes to contend with, the military made bare assertions about its land needs, and seemed to make the same mistake that the public often makes, assuming its property holdings were privileged, holding complete jurisdiction over its land reserves ("unique status", p.33); but these holdings relied on "indeterminate sources of executive power" (p.35), and therefore did not enjoy the protection of legal statute or law code. Congress, in 1958, stepped in again to formalize powers delegated to the executive branch regarding its 'duty to protect' public lands, laying out a legal mandate for the management of wildlife on military reserves, so that they could not be construed as 'implied powers' of the executive branch; but as late as circa 1983, there were still questions about the "legal adequacy" (p.35) of DoD claims to control lands, including the prospect of much "illegal public land control by the various armed forces" (ibid.) The harm that this militarized land has inflicted (e.g. on private landowners evicted from their property) is somewhat obscured in this legal treatment of the issue. There is mention later in the book (in Chapter 9) of "farmlands condemned by the army" (p. 266), and internally displaced persons (d.p.'s), that is, "farm families who worked the land, then found themselves evicted on less than one month's notice to make way for army munitions" (p.266). But in addition to this color that could have been included, Chapter 1 misses perhaps an even greater opporunity to mention that such land grabs continued in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. In the 1970s and 1980s, there was a movement afoot to enlarge at least three U.S. domestic training bases: at Fort Hood (Texas), an expansion intended to compensate, ironically, for the 62,000 acres of firing range already contaminated with unexploded ordnance (UXO); Fort Riley (Kansas), where commanders intended to double the size of the land under their control; and Fort Carson (Colorado). All three of these proposed land confiscations reportedly encountered public opposition from local residents, who somehow effectively lobbied Congress to prevent them. These stories would be worthwhile re-telling in detail. e.g. When Fort Carson acquired a substantial slice of Colorado near the New Mexico border, it acquired 235,000 acres (367 sq.mi or 951 km2), in the early 1980s. Unsatisfied, from 2007 to 2013, the U.S. Army intended to expand the Piñon Canyon Maneuver Site in southeastern Colorado, so as to triple its size, by adding 418,000 acres (653 sq. mi, or 1,690 km2) of private ranch land, for a total land area of 650,000 acres (1,015 sq. mi, or 2,630 km²). It was opposition from ranchers, and from a U.S. senator leading the charge against the expansion --in other words, a popular protest movement-- that thwarted the expansion plans, not legal constraints (see mention of Fort Carson, in a different context, Chapter 9). e.g. "When word surfaced about the Army's intentions, the ranchers mobilized quickly, forming a coalition called Not One More Acre! They lobbied 15 county commissions to pass resolutions opposing the Piñon Canyon expansion and won votes in the Colorado legislature and in Congress." ("Ranchers angry over army site expansion", Washington Post, 2007) Similarly, in Wyoming, in a land grab by the U.S. air force, one rancher explained "they want more land, more water, more everything" (quoted, Chapter 8, p.252). There are reportedly millions of acres (between 2 million and 5 million acres) still at risk of impoundment, withdrawal, or seizure, due to Army ambitions (the DoD already has some 25 million acres of land at its disposal, currently); but not to worry, the "Army will be a good steward" of the land as it runs its tanks on maneuvers, the Navy will avoid causing harm to turtles' nests on the beach while practicing tracked amphibious landings, and the Air Force is studying how to mitigate those sonic booms from flights overhead. It was in the early 1990s, apparently, that civilian/environmental opposition to military land withdrawals got organized enough to present "unified opposition" to the U.S. military branches, to the point that "national security was no longer a trump card to gain land concessions [at least in] the West." (Chapter 8, p,253) By the end of the Cold War, "American citizens were no longer willing to accept that environmental destruction was an acceptable cost for national security." (ibid., p.255). Here, the two chapters, Chapter 1 and Chapter 8, are working together to round out a change that took place over a broad arc of time. The legitimacy of military control over lands, that would otherwise be part of the national territory or the commons, is being questioned, and the military's claim to be a steward of the land is being subject to increasing scrutiny.

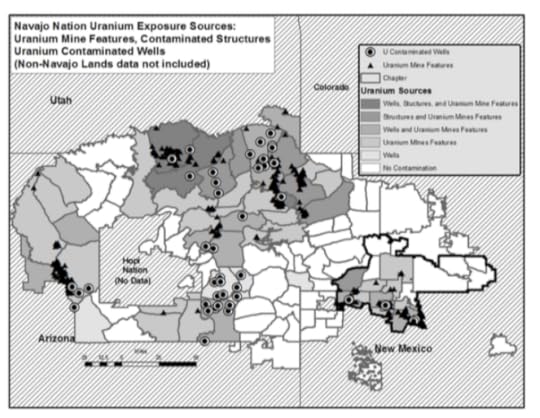

The extent of the lands affected by military interests is surely even larger than the vast tracts under discussion so far: Missing from any consideration here is whether the contracted third parties supplying the U.S. military can continue to write-off portions of the domestic U.S., and/or parts of the world further afield, as they injure lands, water, people, flora and fauna in their relentless pursuit of profits by resource extraction. Consider, for example, what the uranium supply for the U.S. arsenal of atomic and thermonuclear bombs has done to the Four Corners area.

Aren't we better off just sticking to the term "landscapes of contamination" (intro, p.9) rather than debating "the refuge effect" (p.249) for the fauna that happen to be guests of military-controlled lands? Chapter 2, by Neil Oatsvall, opines that the military is capable of a "deep sensitivity to the natural world" (introduction, p.8) because of a nod in the direction of protecting charismatic species (in this case, the sea otter; also see Chapter 8 on the red-cockaded woodpecker, the brown pelican, the Hawaiian stilt, the manatee, the leatherback turtle, etc.).

Chapter 3, by Leisl Carr Childers, attempts to reconstruct people's reactions to nuclear testing, and their consciousness (or lack thereof) that bombs going off upwind means that they--and their livestock--are in turn downwinders "under the shadow of the fallout cloud" (chp. 3, p.84; "downwind" pp.81,90). The essay discusses the popular epidemiology used by non-experts outside the military proper to understand the degree of risk from nuclear bomb tests that they or their livestock might be exposed to. Using inductive reasoning, the average citizen is capable of concluding that "contact with radioactive fallout seemed the most likely explanation" (p.103) for some of the health problems being experienced. (This chapter is reminiscent of other work, monographs such as Sarah Elisabeth Fox's Downwind: A People's History of the Nuclear West, 2014, or Harvey Wasserman's Killing our Own: the Disaster of America's Experience with Atomic Radiation, published three decades ago, and now PDF available online free download, 250 pages.) But frustratingly, none of this realization prompts much of any popular protest, or resistance to nuclear testing (it's the 1950s in Albuqurque, NM). Although there's "near panic" (p.78), "mounting public apprehension" (p.87), "intensified public uneasiness" (p.92), and "increasing concern" among the exposed public (p.93), this degenerates into "lingering public fear" (p.93), and not some bout of raised consciousness or determined opposition. The domestic populace takes no action, at least as far as this chapter is concerned, and instead it's left to 'international public pressure' (p.105) to insist on a moratorium and then an outright ban on above-ground atmospheric tests of nuclear weapons --with no mention, however, of SANE, organized by civil society in the U.S., the group that was instrumental in the passing of the Partial Test Ban Treaty. And in keeping with the detached perspective, it's impossible to say what the author's views are about low-level radiation (LLR) exposure.

You can find a version of the above review published on H-Net (Humanities Net):

https://networks.h-net.org/node/19397...