What do you think?

Rate this book

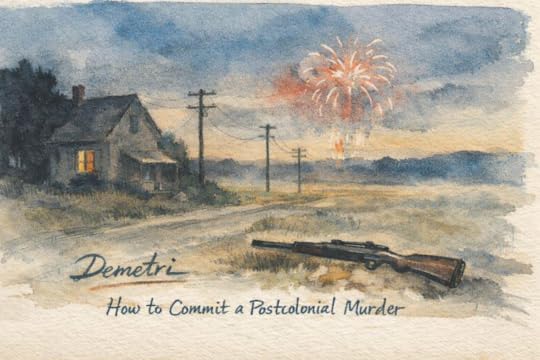

209 pages, Kindle Edition

Expected publication January 22, 2026

… [Amma] planted hundreds of [daffodil] bulbs in our yard during our first fall at Cottonwood Cross, when I was a baby … Every spring thereafter they’d come up through the snow, and every spring thereafter, the deer would come down from the creek and eat them.