What do you think?

Rate this book

400 pages, Hardcover

First published July 1, 2015

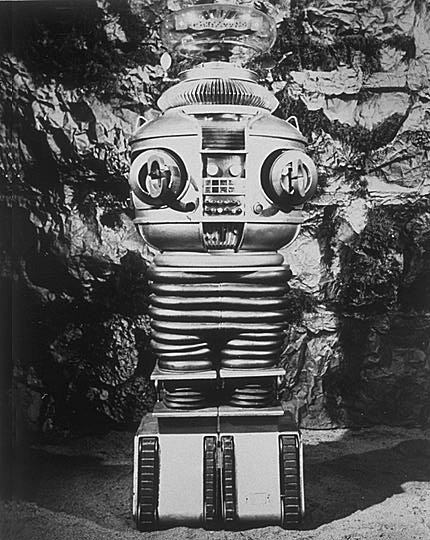

Open the pod bay doors, HAL.

I’m sorry Dave. I’m afraid I can’t do that.

What’s the problem?

I think you know what the problem is just as well as I do.

What are you talking about HAL?

This mission is too important for me to allow you to jeopardize it.- from 2001 A Space Odyssey

For the past half century an underlying tension between artificial intelligence and intelligence augmentation—AI vs IA—has been at the heart of progress in computing science as the field has produced a series of ever more powerful technologies that are transforming the world. It is easy to argue that AI and IA are simply two sides of the same coin. There is a fundamental distinction, however, between approaches to designing technology to benefit humans and designing technology as an end in itself. Today, that distinction is expressed in whether increasingly capable computers, software, and robots are designed to assist human users or to replace them.Markoff follows the parallel tracks of AI vs IA from their beginnings to their latest implementation in the 21st century, noting the steps along the way, and pointing out some of the tropes and debates that have tagged along. For example, in 1993, Vernor Vinge, San Diego State University professor of Mathematics and Hugo-award-winning sci-fi author argued, in The Coming Technological Singularity, that by no later than 2030 computer scientists would have the ability to create a superhuman artificial intelligence and “the human era would be ended.” VI Lenin once said, “The Capitalists will sell us the rope with which we will hang them.” I suppose the AI equivalent would be that “In pursuit of the almighty dollar, capitalists will give artificial intelligence the abilities it will use to make itself our almighty ruler.” And just in case you thought the chains on these things were firmly in place, I regret to inform you that the great state of North Dakota now allows drones to fire tasers and tear gas. The drones are still controlled by cops from a remote location, but there is plenty to be concerned about from military killer drones that may have the capacity to make kill-no-kill decisions within the next few years without the benefit of human input. Enough concern that Autonomous Weapons: an Open Letter from AI & Robotics Researchers, signed by luminaries like Stephen Hawking, Elon Musk, and tens of thousands of others, raises an alarm and demands that limits be taken so that human decision-making will remain in the loop on issues of mortality.

My instructor was Mister Langley and he taught me to sing a song. If you’d like to hear it I can sing it for you.