What do you think?

Rate this book

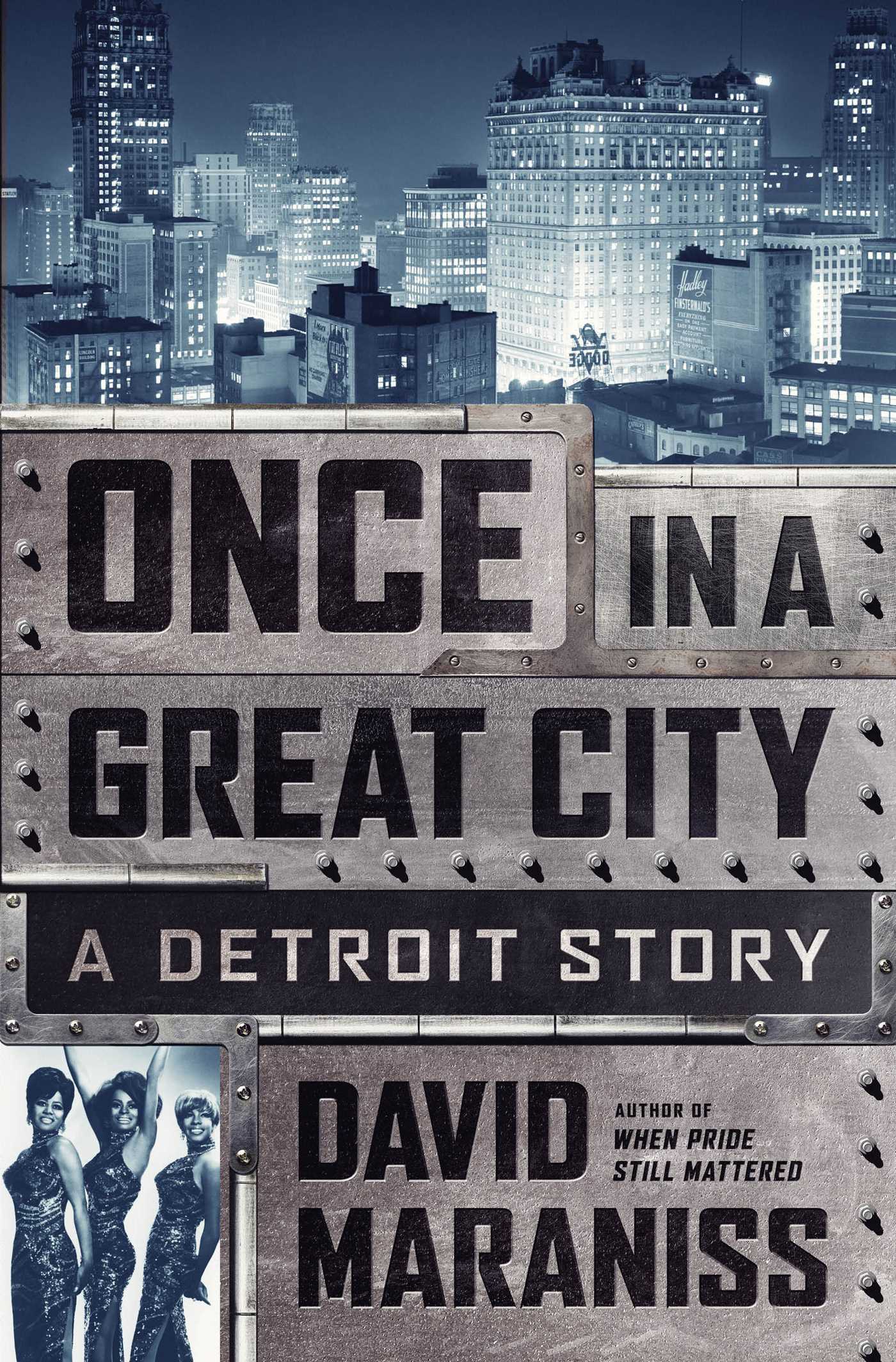

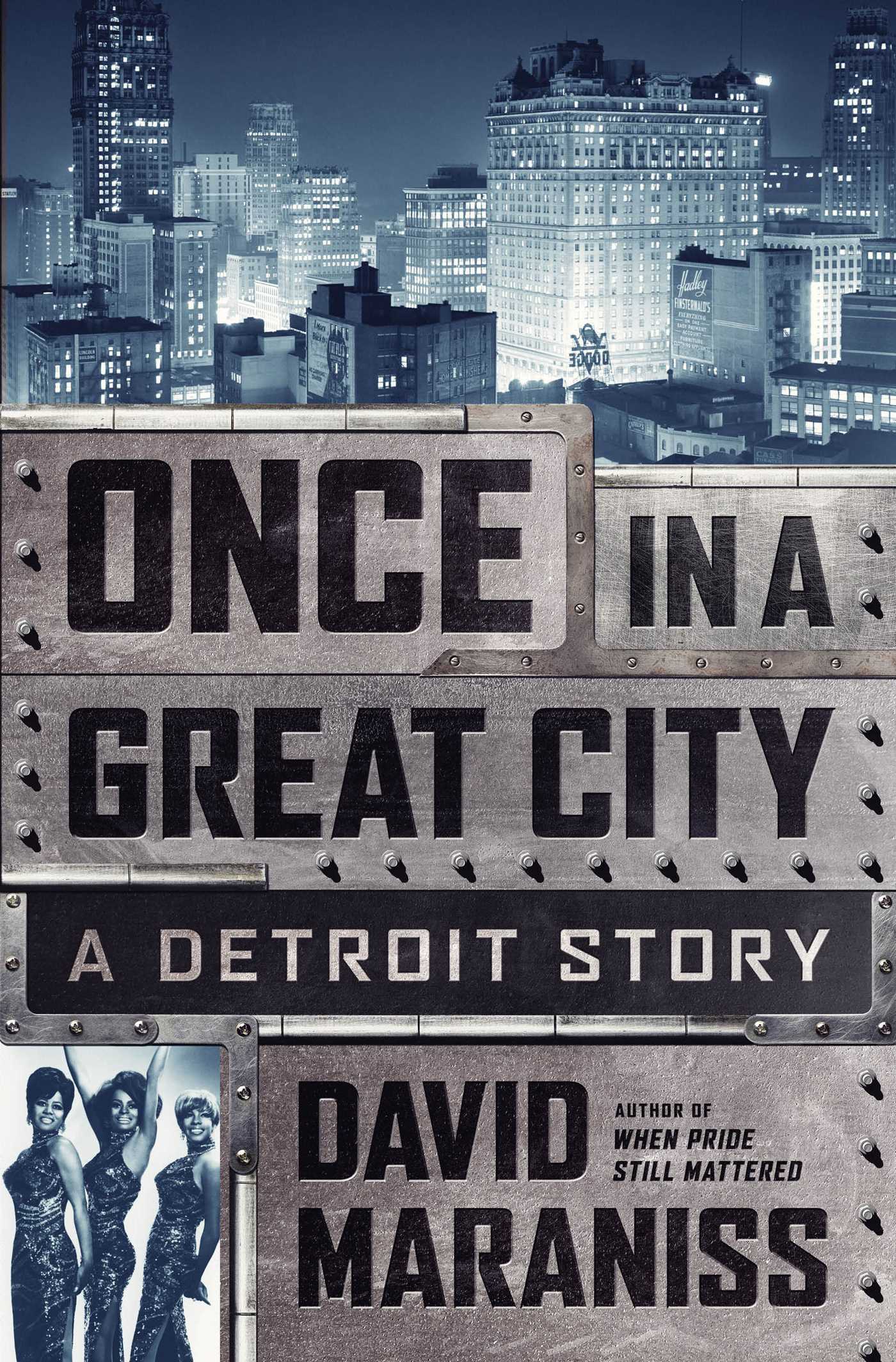

464 pages, Hardcover

First published September 1, 2015

…connecting these was the least appreciated and perhaps most important factor of all: the music teachers and program in the Detroit schools.

Talk to musicians in Detroit and odds are they will recall—vividly and fondly—the teachers who pushed them along. Paul Riser came to Motown in 1962 as a trombone player straight out of Case Tech, a social naif among the older cool-cat jazzmen of the Funk Brothers house band, but also a musical prodigy with skills at reading, writing, and arranging scores that he had learned in the public schools. Harold Arnoldi, the music teacher at Keating Elementary, plucked him out of the crowd at age seven and become a mentor and father figure to Riser, helping him get instruments at a discount and encouraging his development. Then, at Cass Tech, Riser rose under the guidance of Dr. Harry Begian, who inculcated in his music students the classics and fundamentals. “He was like a military drill sergeant, but he did it from his heart,” Riser recalled. “I didn’t understand what he was doing until I graduated years later and got a degree. I was able to laugh about it, his discipline. Harry Begian treat us as ladies and gentlemen and got us ready for the marketplace, attitude-wise, discipline-wise. I sat first chair trombone at Cass Tech, and he saw something in me, again, just as Arnoldi did. That got me ready for Motown.”

For Martha Reeves, the public school influence traced back to her music teacher at Russell Elementary School. “Emily Wagstaff, a beautiful little German lady whose accent was so think I could barely understand what she was saying,” Reeves later recalled. “She pulled me from class five minutes before tick-tock and chose me as a soloist. My public school teachers had the biggest hearts and they were patient, and they could choose. They could pick out the stars and know they can instruct them and fill out their greatness.” At Northeastern High her music teacher was Abraham Silver, who, much like Begian at Cass Tech, had a capacity to teach music theory as well as direct a choir and infused his students with an appreciation for the classics and fundamentals. Freedom thought discipline: once they learned the fundamentals they could move freely into the genres of jazz, pop, and rhythm and blues.

Reeves later remembered how Silver singled her out and then nurtured her. “He went through the whole choir section to see who could sing Bach arias. My name was Reeves, I was near the end. Some others did pretty good but no one really nailed it. So I stood up with my knees knocking. I nailed it. I had never heard of Bach. Or I had maybe heard it on the radio. One of my favorite pastimes as a teenager was listening to symphonic music and trying to hit some of the high notes.” Decades later, recalling the scene, Reeves hit those soprano notes beautifully. “So I did learn a lot listening to symphonic music. But Bach was a new name to me. Hallelujah! We were the first choir at Northeastern to be recorded. And the first choir from Northeastern to sing at Ford Auditorium. The first time I appeared before four thousand, four hundred people. I was seventeen, about to graduate. And that was one of the biggest thrills I can remember in my teenage life, to hear that applause. It was not just for me but for the entire choir, but I was the soloist. No microphones. You had to throw your voice. Abraham Silver. He taught us not only how to sing but how to read it. That made a big difference. That we learned how to read notes. That we did it correctly.”