What do you think?

Rate this book

250 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2009

People are not equally interesting, equally admirable, or equally able to understand the world in which they live.

__________

Many people seem to live in an aesthetic vacuum, filling their days with utilitarian calculations, and with no sense that they are missing out on the higher life.

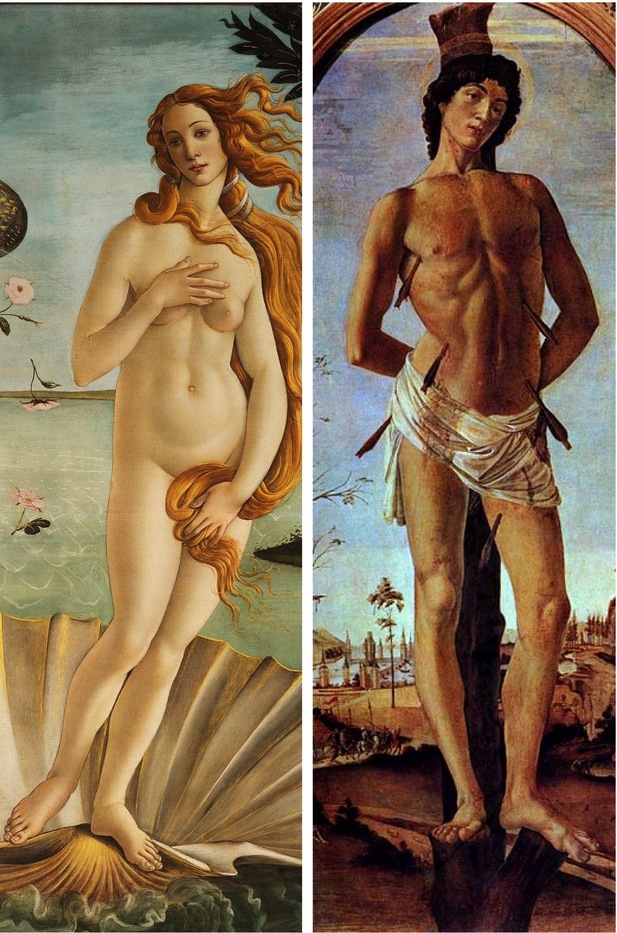

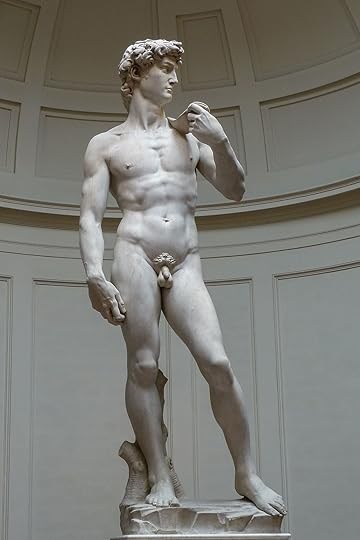

Those ‘higher’ forms of beauty which are exemplified by art . . . For people who don’t know these works of art the world is a different—and maybe less interesting—place . . . It is what art, and only art, can give.

__________

Beauty is vanishing from our world because we live as though it did not matter . . . To point to this feature of our condition is not to issue an invitation to despair. It is one mark of rational beings that they do not live only—or even at all—in the present. They have the freedom to despise the world that surrounds them and to live in another way.

Indeed taste is what it is all about . . .

In a democratic culture people are inclined to believe that it is presumptuous to claim to have better taste than your neighbour.

Many people seem to live in an aesthetic vacuum, filling their days with utilitarian calculations, and with no sense that they are missing out on the higher life.

People are not equally interesting, equally admirable, or equally able to understand the world in which they live.Can this sensibility be learned? Or can it only be learned with people who possess a spark of it to begin with?

Beauty is vanishing from our world because we live as though it did not matter . . . To point to this feature of our condition is not to issue an invitation to despair. It is one mark of rational beings that they do not live only—or even at all—in the present. They have the freedom to despise the world that surrounds them and to live in another way.In that last sentence, Scruton seems to believe (although it's not elaborated here given the confines within which he is writing) in something I greatly, and fundamentally believe in (and which I don't think I've come across in anyone else), which is that although you are inevitably shaped by (and exposed to things which are in) the times in which you live, and all the "culture" (that may or may not be exist, as far as the term culture can properly be used to describe these things . . .) which exists in the times you find yourself in, you are not bound/limited to this: this is not all there is. There are people who have come before us, better people, who produced works (solid works possessing a true integrity and inherent worth/value) which you can shower yourself in, shielded from the refuse which are the products of modern: "culture", ways of life, thoughts, philosophies, "art", anxieties etc, etc, etc, but this must be a conscious choice; but those who know this already know, the people who do not likely never will, or, upon being exposed to it, lack whatever is required to regulate their lives so, or have not reached the conclusions which would lead them to so regulate their lives regardless . . .