“Men must endure / Their going hence, even as their coming hither: Ripeness is all.”

(King Lear, 5:2:10-12)

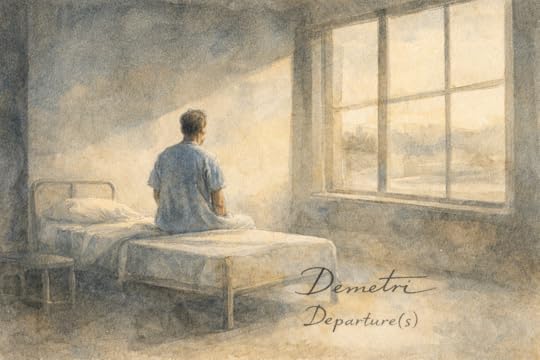

Julian Barnes quotes these lines in his new book, “Departure(s).” It makes perfect sense: the book I am holding in my hands was written by and about an old (which is to say my age) writer who has been diagnosed with cancer and is thinking about his life and his creations and what he remembers. His publisher says the book is fiction, a novel. This may be true: the term has become, let us say, unstable in recent years. Barnes asserts that it will be his last book. This also may be true. It’s almost certainly true, in fact. As I said, Barnes was diagnosed a few years ago with a rare kind of blood cancer. “It isn’t curable,” his doctor told him, "but it is manageable.” (“Incurable yet manageable,” he reflects shortly after learning the diagnosis. “That sounds like… life, doesn’t it?”)

Much of the book -- especially at the beginning -- focuses memory. It begins with Barnes conjuring Marcel Proust’s story in “Swann’s Way” of eating a Madeleine and suddenly being inundated by long-forgotten memories. (No prior knowledge of Proust is necessary.)

(I have to pause here and acknowledge that I’m taking some liberty with the truth. The book actually opens not with Proust but with this: “The other day, I discovered an alarming possibility. No, worse: an alarming fact. I have an old friend, a consultant radiologist, who for years has been sending me clippings from the British Medical Journal. She knows that my interest tends towards the ghoulish and the extreme.” No need to speculate: Barnes gives us a pretty good idea of what he’s talking about.)

But back to Proust. The allusion to “Swann’s Way” sets Barnes off on a lively and eccentric contemplation of memory (“that place where degradation and embellishment overlap.”) Suppose, he posits, you could call to mind everything you’ve done, every thought you've had. “Would you want to know absolutely everything about yourself? Is that a good idea, or a bad one?” An interesting question, particularly (I have to believe) for a writer: “How would you face the record –the chronological record – of all your lies, hypocrisies, cruelties both avoidable and (seemingly) unavoidable, your harsh forgettings, your dissimulations, your broken promises, your infidelities of word and deed? Not just the actual failings but the imagined and desired ones.

“Memory is identity,” he observes more than once in “Departure(s).” Barnes fleshes out the many complexities inherent in the statement. Novelists are story-tellers, and memories the stuff of which their stories are made. But aren't the memories themselves essentially stories themselves? Fabrications “mutating a little with each retelling until it congeals finally into a version which we convince ourselves the truth”? What is fiction in “Departure(s),” and what… well, not fiction? Another good question, but one best left unanswered because it doesn't matter: reading the book is like being in the company of a truly interesting and amusing stranger you’ve just met. Maybe you're sharing a bottle of wine as you listen to him talk about this or that.

That parenthetical addition to the title — “Departure(s) — conveys some sense of what Barnes is up to. He interrupts his discourse on memory to give the reader notice: “Two things to mention at this stage: There will be a story — or a story within the story — but not just yet; and This will be my last book.”

About that story: It involves two people — Stephen and Jean — Barnes met back in college when they were in their 20s. He was instrumental in bringing them together as a couple. In time they broke up but then reentered his life some 40 years later (he is again instrumental in bringing them together). While the story is true, he tells us (though I’m not 100% sure I believe him), Stephen and Jean are not their real names. He promised them “separately” that he would never write about them. (He lied.) Plus, in order to tell a story — “any story” — he has to give “a certain amount of background.” (He breaks the fourth wall and directly speaks to the reader: “Actually, just writing this makes me feel a bit weary. And I wouldn’t blame you if you did too. So I’ll keep most of that stuff to a minimum. You may thank me, or you may not. But as writers get older, either they grow egotistically expansive or they think: contain yourself and cut to the chase.”)

And so he goes in and out of the story of Stephen and Jean (and Jean’s very excitable dog) as they come together, grow apart, come together again, and… so on. Reporting on what they tell him (again separately), what he says in response. They’re difficult people, very different from one another. “I had treated Stephen and Jean as if they were characters in one of my novels, believing I could gently direct them towards the ends which I desired. I’d been confusing life with fiction. I’ll tell you the rest another time.”

Understandably, he keeps coming back to his own situation. His own uncertainly imminent departure. He was writing much of the book during Covid. He penetrates the wall again: “The writer, quarantined in his own home, suddenly victim of blood cancer, while all around a plague is spreading exponentially. It sounds like a bad, or at least derivative, novel.”

He’s careful to stay away from other people as much as he can because he’d “rather die of his own disease, thank you very much, not everybody else’s.’

I imagined myself being rushed to hospital, breathless, speechless, perhaps even unconscious. They see this old geezer and are coming down on the side of straight to ‘end of life care’ when one of them notices that I am wearing a lapel badge. It reads: BUT I WON THE BOOKER PRIZE. And I am reprieved. Unless the gesture looks like an attempt to pull rank, in which case . . . well, I would never find out.

Elsewhere he envisions himself as an old-er man and losing his memory and friends/caretakers, trying to be helpful, suggest that he read his own early books to see if he might recapture who he was (“memory is identity”). They put the headphones on, and you listen to an actor – or perhaps, even, yourself – reading words you had written decades previously. And then what? Does it feel half-familiar? Do you think this must be some book you had read in earlier years? Or might it trigger a genuine memory of writing the words?

So: life, death, writing, fame, love, dreams… (“Departure habitually leads to arrival. Not always, of course… We go, we arrive, we set o in return, and reach home again: we live with this momentum.” Until in the end there is “The Departure which will be followed by no Arrival.”

Barnes reassures the reader that he’s not (or not often) afraid of dying. As an atheist — and support of a group called Dignity in Dying — he doesn’t expect any Thereafter. He shares a story from when catalytic converters were being stolen all the time from cars:

”An old friend and neighbour of mine, disturbed by a noise from the street, opened his bedroom curtains and saw a man half-underneath his car. He rushed down to the front door and shouted ‘What are you up to?’ The man stood up and pointed at him. ‘This has nothing to do with you,’ he said in a threatening manner, ‘Now fuck off back inside.’ Which my friend obediently – and wisely – did. I sometimes think of this incident when I’m musing on illness and decrepitude. It’s just the universe doing its stuff, it has nothing to do with you, so just fuck off back inside, OK? Do you see what I mean?

“…the universe doing its stuff…” Or as Kurt Vonnegut put it many many decades back: “So it goes.”

Do I make the book sound terribly dark and depressing? I hope not because it’s neither of these things, not in the least. It’s touching, profound, playful, tender… Which is not to say the reader won’t finally put the book down with a feeling of sadness of the kind one feels after saying farewell to a beloved friend they may never see again. If “Departure(s)” is in fact to be Barnes’ last novel, it’s a hell of a way to go out.

My thanks to Knopf for a digital ARC of "Departure(S)" in return for an honest review.