What do you think?

Rate this book

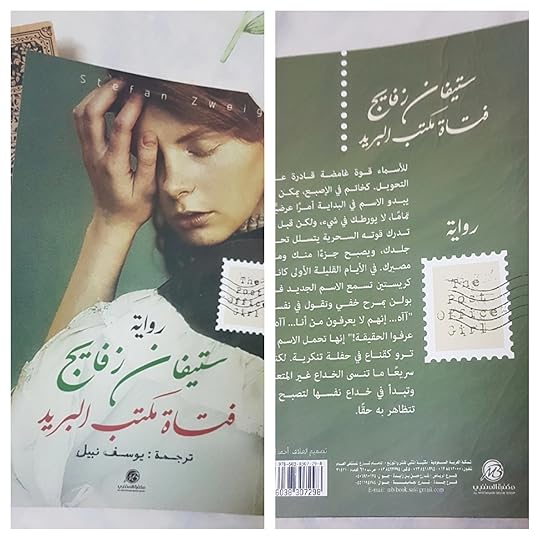

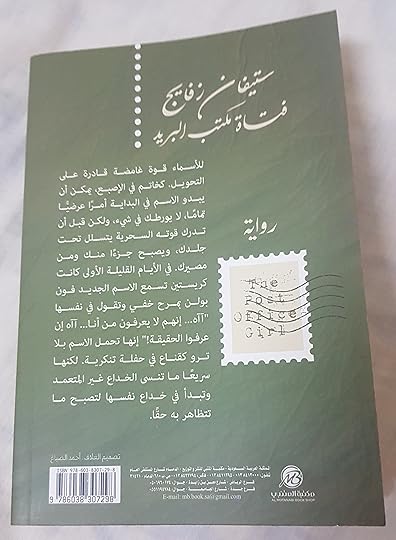

257 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1982

" من علمنا الغش إن لم تكن الدولة؟ كيف كان يمكن أن نعرف بطريقة أخرى أن المال الذي ادخرته ثلاثة أجيال يمكن أن يصبح فجأة بلا قيمة في غضون أسبوعين، وأن تسلب الأسر من مراعيها ومنازلها وحقولها التي كانت ملكها لمائة عام ؟

بحق الله لدينا دعوة قوية جداً ضد الدولة ، وسوف نفوز بها في اى محكمة ! لا يمكنها أبداً أن تسدد دينها المريع لنا، ولا يمكنها أن ترد ما سلبته منا."

ثمة درجة طبيعية من الضغط يمكن لاى مادة أن تتحملها. لدى الماء درجة يغلي عندها، وللمعادن درجة تنصهر فيها، كذلك هو الامر مع عناصر الروح. يمكن أن تصل السعادة إلى درجة عظيمة لا يمكن بعدها الشعور بأي نوع آخر من السعادة. وكذلك لايختلف الأمر مع الألم، اليأس ، الإذلال، التقزز ، والخوف.ما إن يمتلئ الإناء حتى لا يعود بإمكان أحد أن يضيف إليه شيئا.

Why breathe this in day after day, knowing that there's another world out there somewhere, the real one, and in herself another person, who is suffocating, being poisoned, in this miasma…suddenly she hates everyone and everything, herself and everyone else, wealth and property, everything about this hard, unendurable, incomprehensible life.

"من انا إذن؟ طيلة سنوات كثيرة، كان الناس يمرّون من أمامي في الشارع، دون أن يلمحوا وجودي حتّى! ولأعوام طويلة كنت أعيش في قريتي دون ان يمنحني احد شيئًا او يفكّر في ذلك اصلًا. هل يكون الفقر المنهك بغشاوته المغلقة هو السبب؟ أم ان هناك شيئًا ما كان محتجبًا في داخلي وقد تجلّى فجأة للناس؟ هل من المعقول أنني أجمل مما كنتأعتقد وأكثر أناقة وجاذبية؟ من أنا؟ من أنا في الحقيقة؟"

"المخيلة تنشئ دومًا ما هو أكثر رعبًا من الواقع، وما سيحدث يخيف المرء أكثر مما حدث فعلًا."

When will it be me? When will it be my turn? What have I been dreaming about during these long empty mornings if not about being free someday from this meaningless grind, this deadly race against time? Relaxing for once, having some unbroken time to myself, not always in shreds, in shards so tiny you could cut your finger on them.

Meat too expensive, butter too expensive, a pair of shoes, too expensive: Christine hardly dares to breathe for fear it might be too expensive.

How could she ever wear such splendid and fragile treasures without constantly worrying? How do you walk, how do you move in such mist of color and light? Don’t you have to learn how to wear clothes like these?

But how can I hide, how can I disappear quickly before anyone sees me and takes offense.

How terrible it is to have to live here, and why, who’s it for? Why breathe this in day after day, knowing that there’s another world out there somewhere, the real one, and in herself another person, who is suffocating, being poisoned, in this miasma. Her nerves are jangling. She throws herself down onto the bed fully clothed, biting down hard on the pillow to keep from screaming with helpless hatred. Because suddenly she hates everyone and everything, herself and everyone else, wealth and poverty, everything about this hard, unendurable, incomprehensible life.

when the war has ended but poverty has not. It only ducked beneath the barrage of ordinances, crawled foxily behind the paper ramparts of war loans & banknotes with their ink still wet. Now, it's creeping back out, hollow-eyed, broad-muzzled, hungry & bold, eating what's left in the gutters of war.The prose is amazingly fluid, graceful & at times almost entrancing, taking the reader back to an imperial time when the world was for the few and for the very few. But in the midst of almost unfathomable austerity, one man who plays Schubert & Mendelssohn late at night, when the neighbors are all asleep is described as a calligrapher whose handwriting is "almost Koranic, with its delicate curves & shading, done mostly for the sheer joy of it."

An entire winter of denominations & zeroes snows down from the sky, hundreds of thousands, millions, but every flake melts in your hand. Money dissolves while you're sleeping, it flies away while you are changing your shoes. Life becomes mathematics--a mad whirl of figures & numbers, a vortex that snatches the last of your possessions into its black, insatiable vacuum.

She sits all through the night, frozen with fury. Nothing in the hotel reaches her through the upholstered doors; she doesn't her the untroubled breathing of sleepers, the moans of lovers, the groans of the sick, the restless pacing of the sleepless, doesn't hear the through the closed glass door, the morning breeze already blowing outside; she's aware only that she's alone in the room, the building, all of creation.In the early morning, Christine flees in the threadbare togs she came in, almost unrecognized by the few early risers, returning to her previous, anonymous shell of identity. In time, in the streets of Vienna she meets a former soldier named Ferdinand, who is also bereft of hope, someone "who is not a Boshevik, a Communist, Socialist, Fascist or a capitalist", considering his work his only refuge, except that the work has disappeared & he has been rendered redundant. Seemingly, Ferdinand who once had ideas & a long-thwarted vision for himself, now is seen as merely among the dregs of an empire in decline.

I'm 30 years old & 11 of those years have been wasted. I'm 30 & still don't know who I am. I still don't know what it's all for. I've seen nothing but blood, sweat & filth. I've done nothing but wait & wait some more. I can't take it any longer, being at the bottom & on the outside. It makes me livid & it's driving me crazy. Time's running out while I do odd jobs for other people, while I am just as good as the architect who's telling me what to do. I know as much as the guys at the top. I breathe the same air & the same blood runs through my veins. I just showed up too late. I fell off the train & can't catch up no matter how fast I run.The pair of lonely, disenfranchised but well-meaning souls bond but not in anything resembling a loving relationship; rather, they are more like two shipwrecked figures, clinging to to each other as kindred spirits, without much hope of ever finding a safe haven, a welcoming refuge. In fact, "when they thought of each other, it wasn't with feelings of passion or love but with something like pity--not the way you think of a lovers but rather of a friend in trouble."