Oh, Lucia,” the captain said softly, “you are so little and so lovely. How I would have liked to have taken you to Norway and shown you the fjords in the midnight sun, and to China – what you’ve missed, Lucia, by being born too late to travel the Seven Seas with me! And what I’ve missed, too.”

What’s in a name? Lucy Muir’s has its root in Italian and Gaelic, the sparkle of light upon the ever changing sea, a dream of adventure and beauty for a young woman that has been strait-laced into one of those Victorian whalebone corsets until she can barely breathe.

They left her nothing of her own. They chose her servants, her dresses, her hats, her books, her pleasures, even her illnesses. “Dear little Lucy looks pale, she must drink Burgundy,” and “Poor little Lucy seems to be losing weight, she must take cod-liver oil.”

It wasn’t suppose to end like this. Born at the turn of the last century, Lucy has lived until seventeen in her father’s house, sheltered from hardships and reading romantic novels about heroines being swept off their feet by handsome strangers. Such a stranger kissed her in her garden of innocence, and Lucy’s happy ever after turned sour almost overnight under the relentless dreariness of a clueless husband and of two bossy, know-it-all sisters-in-law. [ “you don’t know how humiliating it is to have to ask even for a penny to buy a stamp.” ]. The premature death of her husband served only to exacerbate the pressure on the young widow to conform to the expectations of her relatives.

“This,” said little Mrs. Muir, awakening one morning to a beam of March sunlight striking through the eastern window across her face, “this has got to stop. I must settle things for myself.”

>>><<<>>><<<

What’s in a name? R. A. Dick is a pseudonym, suggesting to potential readers a manly, vigorous pen ready to do battle with major philosophical questions. A woman writing the life story of another woman, who lived the best part of her life perched above the sea in an isolated cottage, could not possibly use her own name if she wants her book to sell!

Lucy Muir is herself writing a book, a novel within a novel, both to make ends meet and to put on paper the deepest desires of her soaring spirit. Gull Cottage, the low rent house she rents on a clifftop above the sea, is supposed to be haunted by the ghost of its previous owner. Whether Captain Gregg is real or just a figment of the girl’s imagination is actually irrelevant. What he represents is the desire to live your life on your own terms and not for the pleasure of bigoted, repressed old maids. What matters is the freedom of the mind and the pursuit of happiness, even if it leads you to a lee shore full of hidden rocks, to use some nautical imagery.

“Writing is very different from painting your face or displaying the naked body in the limelight,” Cyril said coldly.

“I don’t see why,” argued Lucy; “personally I think displaying the naked mind between pasteboard covers can do more harm.”

“Sometimes you say the most extraordinary things,” said Cyril. “Are you displaying your naked mind in this book?”

Lucia Muir has a beautiful mind and a hidden inner strength that refuses to bow under misfortune. So does Captain Gregg, who grabbed life by its horns and sailed the Seven Seas before retiring to his dream cottage by sea. They should have sailed together, but have to make do with a platonic friendship across the great divide, holding loneliness at bay with intimate conversations.

She sat there, staring at the ghost of her own happiness.

Is the ghost from the title the actual apparition of Captain Gregg, or a metaphor of the way life finds ways to crush our dreams? Captain Gregg urges Lucy, and us, to at least give it try, fight until the last drop of breath, enjoy the little things that are within your grasp – a friend, a sunny day, a loving pet, a good book, a letter from a loved one, an organ concert in a gothic cathedral.

It was strange, thought Lucy, how much greater and more lasting the work of man’s hands and mind was than man himself. Looking up at the exquisite tracery of the vaulted roof, listening to the majestic music pealing up to join it, she felt dwarfed and humble, yet raised up in spirit beyond her own little ant hill of living.

>>><<<>>><<<

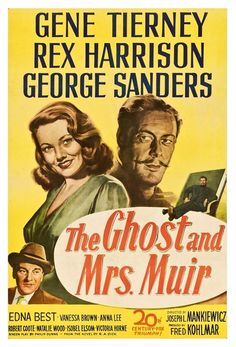

I held out on watching the movie until I could read the novel that inspired it, and I’m glad of this decision. The classic film captures the spirit of the book beautifully, and the casting of Gene Tierney and Rex Harrison was truly inspired. Still, the story itself was streamlined and centred on the romantic part of the novel, on the deep affection between Lucia Muir and Captain Gregg.

The relationship of Mrs. Muir with her children (two in the novel instead of one in the movie) is much more important in the novel, and explored in more detail over the decades of Lucy’s stay at Gull Cottage.

“I don’t want to interfere with my children’s lives any more than you do, but I want them to be happy. Must growing up always mean a breaking up?” she asked sadly.

“No, but it often means a breaking away,” the captain said. “And you wouldn’t want them to stay anchored for the rest of their existence, growing barnacles all over them and rotting away with rust.”

The older boy, Cyril, grows up in the image of his father : sanctimonious conformist, seeking a career in the clergy and judging other people from the high pulpit of his old-fashioned morality. The girl, Anna, dreams of becoming a dancer, of adventure and of love and of laughter. Lucy Muir loves them both and hides her own dreams under a stoic, benevolent smile. Grown up and successful in their careers, Cyril and Anna are trying to convince an older Lucy to give up Gull Cottage and move in with them before illness and money problems overwhelm her. But the little house above the cliff, with the brass telescope to look at the ships passing in the Channel and with the forbidding portrait of Captain Gregg hanging on the bedroom wall is where Lucia is most true to herself.

Impossible to explain, even to Anna, that loneliness was not a matter of solitude but of the spirit and often much greater in company for that very reason.

The end of the story is the end of any story: the closing of a page and the start of a new adventure, with new actors and with new scripts, while the old ones are ‘dropping from the tree of life like autumn leaves’

Josephine Aimee Campbell Leslie has written a true gem of a story, delicate and beautiful and poignant to the point of tears. A ghost story that is a love story that is a feminist manifesto that uses gentle prodding instead of a sledgehammer of slogans.

I would have loved to meet in real life, whatever that is, both Lucia Muir and Captain Gregg.