What do you think?

Rate this book

282 pages, Kindle Edition

First published January 1, 2009

The struggle for life and dreams don’t go together, poetry and salt fish are irreconcilable, and no-one eats his own dreams.

That’s how we live.

And he watched.

But why watch a girl; what use is that, what does it do for the heart, uncertainty; does life become better in some way, more beautiful?

Hopefully he’ll be buried in snow and the Devil will take his remains at the first opportunity. The boy looks around but sees nothing through the blowing snow, the snowfall, knows nothing but his own fatigue…

لماذا هو خطر؟

هو يهدد بتغييرنا، يجعلنا نشك، يرغمنا على مراجعة تصورنا للعالم، وامثال هؤلاء الرجال اعتبروا دائما خطيرين. نحن نفضل الموافقة على التحريض ، نفضل التجريد على المحفز، نفضل الخدر على التنبه. ولهذا يلجأ الناس الى الاغاني الشعبية بدلا من الشعر، لهذا لا يشككون في الاشياء اكثر مما تفعل الخراف،

أما انت فمختلف جدا..

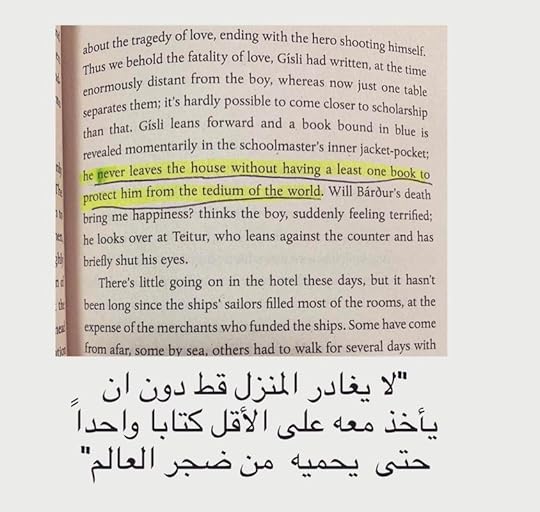

أنت تمد يدك إلى الكتب، تنظر فيها

أعتقد أن ذهنك لا يتوقف عند بيوت الشعر السفيهة والبغيضة

الثلج يتساقط بكثافة عظيمة، إلى درجة أنه يربط السماء بالأرض.

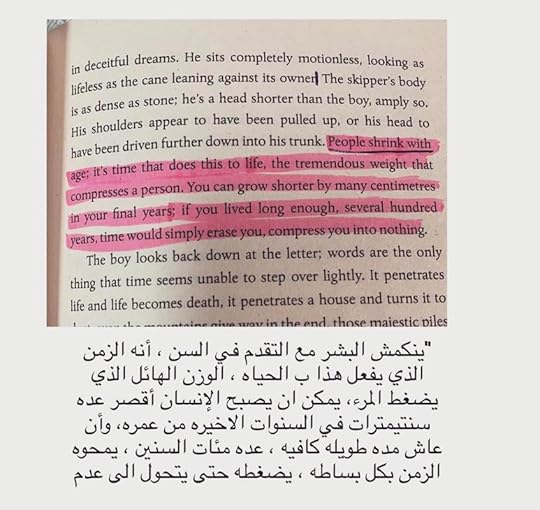

الكلمات هي الشيء الوحيد الذي يبدو أن الزمن لا يستطيع أن يطأه باستخفاف. هو يخترق الحياة والحياة تصبح موتا، هو يخترق بيتا ويحوله إلى غبار، بل حتى الجبال نفسها تفسح له المجال في النهاية، تلك الأكوام الملوكية من الصخر..

إلا أن بعض الكلمات تبدو أنها تتحمل قوة الزمن المدمرة،

هذا غريب جدا؛ فهي تتآكل بالتأكيد، ربما تفقد بريقها قليلا، بيد أنها تصمد وتصون الحياة التي مضى على رحيلها زمن طويل، تصون دقات القلب المندثرة، أصوات الأطفال المندثرة، تصون القبل المغرفة في القدم

بعض الكلمات قواقع في الزمن، وضمنها ربما ذكريات عنكم.

"Dois homens imersos nos seus pensamentos enquanto viajam sob um temporal daqueles não é uma coisa simples, tendo em conta que se tem de usar toda e energia apenas para continuar a caminhar em frente, ir de um lado para o outro sem morrer, o que significa que pensar e, além de tudo isso, tentar perceber a vida deve ser algo épico. Eles abrem caminho através da neve e do vento, dois homens à procura de si mesmos; encontrarão ouro ou apenas pedras pardacentas?" (p. 191-192)

"Mas tu, irmão, precisas de chegar lá abaixo vivo e depois derrotar a tempestade escura que existe dentro de ti; é essa a tua luta, é onde deves travar a tua luta de vida ou de morte." (p. 261)