What do you think?

Rate this book

256 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1951

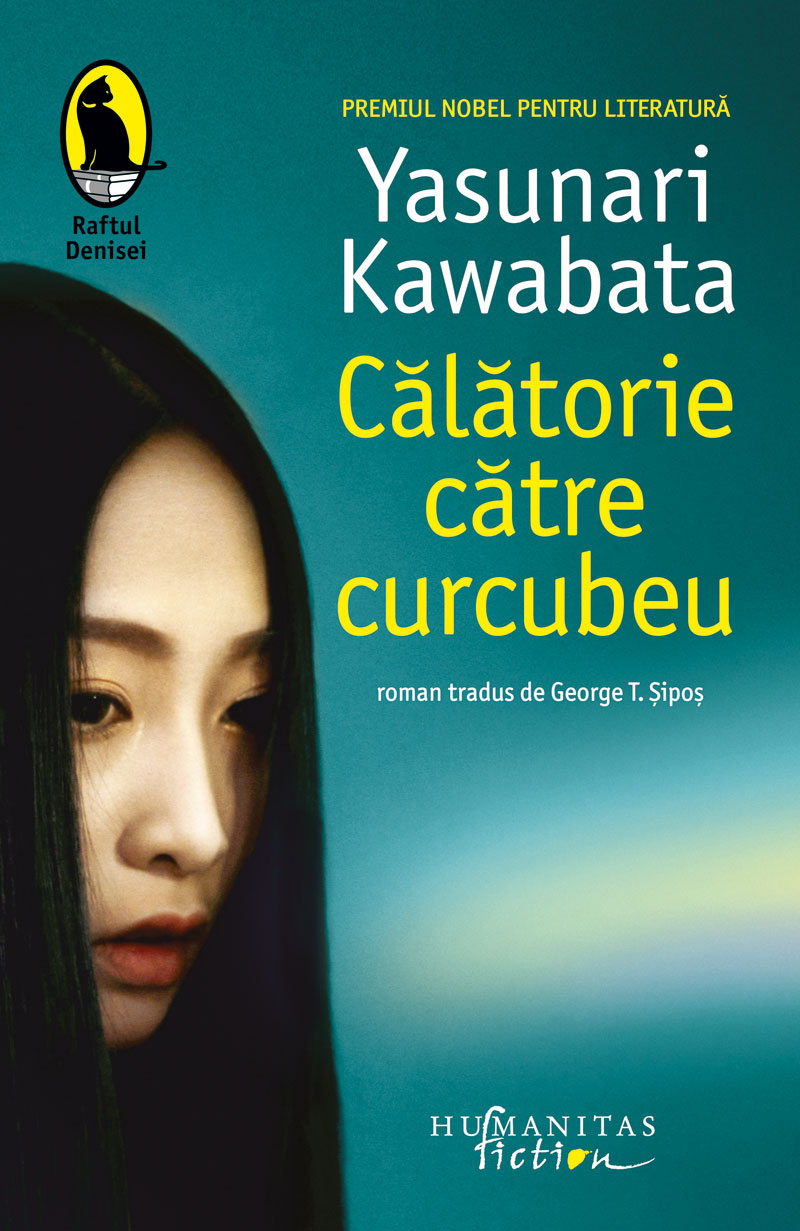

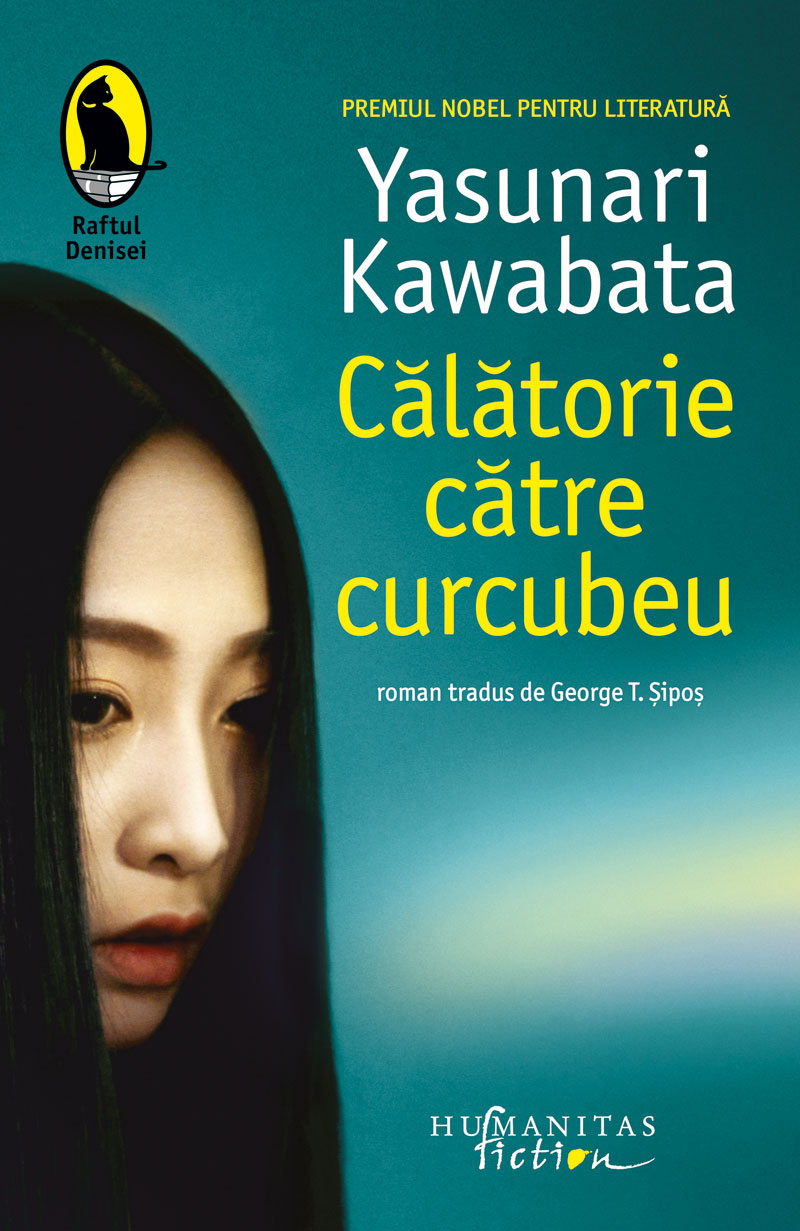

"The dead knew no wounds; these injuries of the heart existed only for the living." (197)I thought that I had read all of Kawabata's novels translated into English, but then I came across The Rainbow and realized that I somehow missed it. It's a slow, meditative story about the architect Mizuhara and his two daughters—Asako and Momoko—by different women; and, as it turns out, the search for a third daughter—Wakako—by yet another woman. As we learn more about the characters' history, the wounds from their pasts mirror those of post-war Japan. The landscape—with the rainbow as a central image—speaks of both the ephemeral and eternal (eternally ephemeral?) nature of beauty. The novel opens with a focus on Asako's perspective but eventually shifts to that of Momoko, who becomes the dominant presence. I wish there had been more of Asako, since I found her to be the more interesting character. Overall, the novel isn't as good as some of Kawabata's others—like The Old Capital or Thousand Cranes—but the interplay between surface-level placidity and the at times rather violent undercurrent of emotions is fascinating and produces some of the novel's most compelling scenes.

"It's like they say: The beauty of a single flower is enough to reawaken one's will to live." (119)

Stagnant clouds that foretold snow hung low over the surface of the lake. Though they seemed to extend across the entirety of the surface, there must have been a gap somewhere out of sight, as the far shore remained lit by a brilliant band of light. In front of the rainbow, soft beams of sunlight were glistening over the water.

The rainbow rose only as high as that band of light.

It looked as if it were climbing almost directly up into the sky. Perhaps because only its base could be seen, the rainbow seemed all the wider. To trace an arc, it would have to be truly gigantic, ending very far away indeed. But of course, only the base of the one side was visible.

On closer inspection, though, Asako realized that the rainbow didn't have a base at all. Rather, it looked as though it were floating in midair. It half seemed as though it were rising out of the water, and half as though it were rising from the ground of the far shore. As she followed its arc upward, it wasn't clear whether it disappeared into the clouds or before reaching them.

The rainbow appeared all the more vivid for its being cut so short. It seemed to call out to the clouds with a sense of sorrow as it ascended into the heavens. The more she looked at it, the more strongly she was taken by the feeling.

The clouds were of the thick, leaden kind, reaching down to the far shore like dark splotches of ink hanging motionless over the horizon.

The rainbow disappeared from sight before the train reached Maibara. [6–7]