What do you think?

Rate this book

525 pages, Paperback

First published April 13, 2023

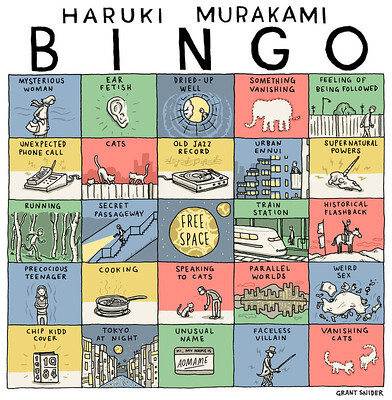

‘I never plan. I never know what the next page is going to be. Many people don't believe me. But that's the fun of writing a novel or a story, because I don't know what's going to happen next. I'm searching for melody after melody.’

‘As Jorge Luis Borges put it, there are basically a limited number of stories one writer can seriously relate in his lifetime. All we do—I think it’s fair to say—is take that limited palette of motifs, change the approach and methods as we go, and rewrite them in all sorts of ways.’

‘To create a special, comfortable spot to gather lots of books, and to have many people freely read them—for Mr. Koyasu, that was the ideal world.’

‘To believe in the reality of a single soulmate is to believe that every lonely life exists because someone didn’t travel towards someone else. A child dies somewhere and then, decades later, someone lives a series of unsatisfied days. Watches the game shows alone & goes to bed early, each day its own small apocalyptic orchestra of near-silence…it is like being held, in this way, by a lover from a world that has already ended. A different lover for every reflection in the room. And yet, when I wake, someone I loved once is still alive, somewhere else.’

’The situation of the town surrounded by walls was also a metaphor of the worldwide lockdown. How is it possible for both extreme isolation and warm feelings of empathy to coexist?’

Courtesy to New York Times.

Courtesy to New York Times."মাঝে মাঝে মনে হয় আমি যেন কারও, কোনো কিছুর ছায়া," এমনভাবে বললে যেন গোপন কোনো কথা ফাঁস করছো। "এখানে যে আমি আছি, তার কোনো অস্তিত্ব নেই, আমার আসল অস্তিত্ব কোথাও অন্য জায়গায়। এখানে যে আমি আছি, সে দেখতে আমার মতো হলেও আসলে মাটিতে বা দেওয়ালে পড়া আমার ছায়া মাত্র...এরকমই মনে হয় আমার।"