What do you think?

Rate this book

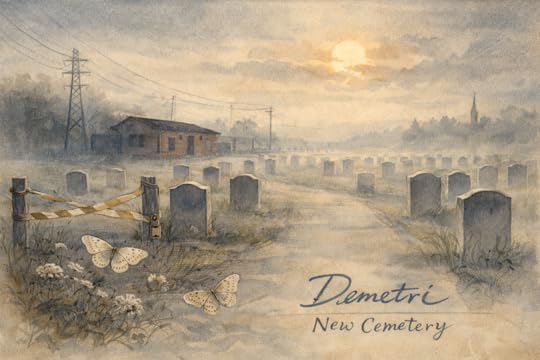

120 pages, Hardcover

First published March 1, 2017

I died and went

to Bristol Parkway

for my sins,

interchange

between soul and flesh

&

the whispered half-rhymes

of earth and death

on the spade’s tongue.

the dead are patiently

killing time

between visiting hours,

deaf, blind, mute

and numb,

unable to love

but capable still

of being loved.