What do you think?

Rate this book

373 pages, Mass Market Paperback

First published February 1, 1991

Forever lost in the seductive madness of a world out of timeMuch more witchcraft/pagan ritualistic than I expected from the blurb (and I feel like a background in such practices might help with some of the contexual references). Utterly, madly unique - now that I have gotten used to its rhythm, which I found jarring and alien at first, I can't really put it down. I would like to listen to the author read it as an audiobook once I finish, to see if I experience it differently a second time around. Here's a sample of the text. It is from the first page onwards, and I can attest that the style is static:

Ariane and Sylvie had spent endless hours spinning fantastical worlds out of the depths of their shared imagination. But when Ariane returned for a long overdue visit, she found herself swept up by old Sylvie-sung spells, caught by the same madness - or was it magic - that still possessed her friend. And even as Ariane sought to recapture the dreams of their youth, Sylvie vanished, lost in some real or otherworldly woods. For Ariane, the search for her missing friend would send her on a quest no mortal could hope to complete, as she journeyed into a darkness far deeper than night to challenge an enemy who had stopped Time itself...

There was a green bough hanging on the door. The year was old, and turning lightward, into winter. Cold and waning, at the end of her long journey, Ariane looked back the way she'd come. Bare woods, bright wind that shook the rain from naked trees, a stony slant of field: the earth lay thinly here. The trees stood lightstruck, hill beyond blue glaze of hill. Then it darkened again, turned cloud and clods of earth, and crow-blotched trees: a drizzling thaw.Gilman's just getting going. Partway through the next chapter, a new voice:

She turned back on the doorstep, and stamped her muddy feet. While we poor wassail boys do trudge through the mire sang mocking in her head (though her tape ran silent). They could beg, she though ruefully: they brought things, garlands - Dear, oh dear, I've done it now. Should I turn my coat? Or break a twig of holly? Snare a wren? Would I know one?

Softly, she rapped at the door. No answer but the wind. Cold by the door, it sang. Louder. Again. A crow yelled. Round the side? Another door, a garland, muddy boots. She peered in at the window. It was dark in the front room, so she saw her face, a late pale moon, and trees with brass pulls and leafless tallboys and a chair of yew; but a fire burned: she saw it in the glass among the branches, burning in the air.

"Sylvie? Hye, Syl?" No one there. The rain came on, sudden, cold and sharp. A wind in the door blew it open. She went in.

Doleful and crumpled as a child, Ariane sloughed her bundles, dumped her books and bags and suitcase, and wriggled out her backpack. Her air of gravity and desolation was, she knew, rather spoiled by her wraggle-taggle trail of clutter. In the eluding mirrors by the doorway, in her long coat, she looked a cross between Prince Hamlet and King Herla's rade, distraitly wandering through time. In comes I, little Johnny Jack, with my obsessions on my back. An owlish, cat-stumbling sort: but her own absurdity did not console her.

Dripping, she wandered toward the kitchen, ill at ease. She had no place here. Time, that had changed nothing in this house, had estranged her; yet she knew no other haven. She hung back at the doorway, at once fond and guilty and forlorn, coming back to what was never hers. She'd not been asked.

Tha'st tholed a few fell winters, awd lass, he thought: tha'st seen wood and waste. Cawd now: would tha like my awd haggard coat?I wasn't quite flummoxed - I know an Northern accent when I read and hear one. But the hard part for me were passages full of ritualistic and Tarot card references that I struggled to follow. For example, pages 31-32:

The stone was silent. She had never spoken to him; she was not always there. Some said she walked the moors, peering and prying into sheepfolds, owling after souls. But he thought she alone stood, unmoving, though all else turned: hills, clouds, and reeling stars.

He slept in a ruined sheepfold, back of Cloudlaw, and dreamed; he lay on the fell, stark cold and turning to a cloud of stone, stars icy at his cheek, unturning. He was blind. His mouth was stopped with earth, ribs hollowed round a heart of stone: but hands took root, thrawed sinews down and downward, warping. He were tree. Awd craw i't branches, cawed and cried: Bone, bone o branches, ah, and eyes o leaf, o leaf. Leaves falled away til dust. Bones stood bare. But hands, they hawded fast, til they warked i't earth. Hand scrat at summat sharp, not stone by fire-warked: cawd iron, siller, gowd. Awd broken ring, he thought. Awd moon. Could never get it back i't sky, were darkfast. Cawd and dead. But the ring grew fast to him, turned O and handfast. Moon leamed under earth. O now he saw: the fell was cloud, and starry back of cloud, and deeper still. And all turned headlong, he was branching into dark and moon, turned lightfast with his roots in sun. Broke leaf. Bright swans above him, and his leaves arising in a crown of wings, and crying out: a thrang of birds. He woke to a fleeting sense of joy, winged with a glory and taloned with want.

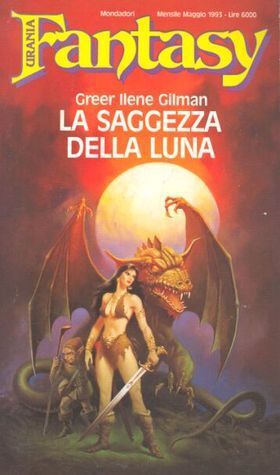

The cards lay scattered all about her. Sylvie had been playing with them, had left them as they fell. Ariane felt a pang of jealousy for her creation, so lightly held, profoundly known, yet occult to her own desire; she longed for Sylvie's careless grace of insight. She had never seen the lands beyond. She smoothed out a bent card and began to gather them; the paused, looked sidelong. Sylvie worked on, unheeding. Ariane half turned aside. Warily she shuffled and covertly laid out a handful of the images in a wavery huddling sort: not longways, but a knot of nine. What then? Knotting and unknotting the unravelled fringes of her shawl, she fell into a blurry revery.The Italian edition, La saggezza della luna, translates to "the wisdom of the moon", rather than the directional vector my mind always traced when reading "moonwise". What totally lacks wisdom, however, was this choice of covers:

Here was the Witch, a mirrored figure, dark, undark of moon, chiasmic; there, aslant of it and sinster, the Wren turned tail. Unlight, unturning. Blood. And there, the Swans, reversed: black frost and barren labor, the weaving of nettleshirts in silence to unspell; earthbinding. The Cup was inmost. Being stone, the child was blind; the water of the fountain wept for it, slow tears, unsalt. The cup it held was cracked; the moon lay drowned in it, unseen, as deep as heaven in the shallow leafy water.

Now, she said, I am that O, that eye within the maze, the moon's garden walled in thorn: my clew is light. Now I will journey outward, will undo the knot of thorn. Will see.

Beyond her lay the wood, Sylvie's element, undreaming. A wind in her boughs stirred Sylvie's darkness, shook the rain from her bright leaves; it shivered starlight in her living water. Even in her stillness she was poised, like the moon new-bent in heaven, like a sword. Ariane had only to find the door into the wood - Witch or Wren or Tower - and walk through it as Sylvie did, becoming wood and journeying and moon, at once the traveller and the tale.

She could not. She was darkfast, vexed and riddled at every turn: a captive in the black-thumbed, ink-blotched garden, in the papery henge of cards. Staring, she unfocused; the woodcut image slewed and blurred. She saw only the configured cards in a knot of mirrors, oppositions, ambiguities, turning ever inward to the maze, the cup, the moon: which was illusion, a mirror at the heart. No other where. She stared harder, til it broke in tears, dissolved: the water's tenure of the moon.

No door, no dance, no clew. Uncrystal.

I child and I devour; I am grave and lap, annihilation and O reborn: light eaten by its inward fury, crown rising from its root in darkness..."Lap and grave", both "birth and death", "making and unmaking" are constant companions and intertwined within a variety of characters rather than simply juxtaposed between opposites (though I say that, and find myself immediately wanting to contradict that.). This book is incredibly complex. It's a bit above me, if I'm honest - I found it challenging but self-improving. I have never read a book like this before, and I'd be surprised if there are many more like this out there.

But in Cloudwood it was endless hallows. There no wren was slain, no seed was scattered; though he cried the ravens from the turning wood, no winter ever came to green. The gate was lost... [p 23]

Two young women, Ariane and Sylvie, find themselves in balladland: in a chilly wintry wood, or on a moor, in the world of Cloud which they invented (or discovered) in a synergistic gleeful season of storytelling when they were younger. Ariane journeys through Cloud and encounters a child who is also, perhaps, an ancient deity or power: Sylvie's journey is (or seems) shorter, and she travels with a tinker who becomes her friend, but who, like the child, may be something more. There are two witches, goddesses, forces: Malykorne and Annis. Annis is winter and wants to freeze time. Mally wants spring, and the cycle of the year.

For long swathes of this novel I was not sure I understood what was happening: but the plot is just one layer of this novel, varnish or garnish over an intricately woven web of words. There's a lot of north-country dialect here -- specifically northern English, with its Nordic roots ('Tha'st nodded again, and t'cake's kizzened up') -- and though the wood that Ariane and Sylvie enter seems to be somewhere in North America, there is a European, perhaps a British, feel to it. The wren is hunted, there are stone circles and thornbushes, scarecrows and stars, bleak fells and homely farmhouses shuttered against the night. The language is seductive and incredibly dense. I think I recall someone saying that reading Moonwise was like being inside a poem by Gerard Manley Hopkins ... though there are also moments where it seems about to break into iambic pentameter, and the text is studded with echoes and iterations of folk-song, ballad, fairytale. Ariane, and especially Sylvie, bring a touch of modernity too, albeit modernity as of the novel's 1991 publication: '"What has it got in its 'pocalypse? Tell us that, precious."'

I have attempted to read this novel more than once and been distracted by mundanity: turns out what I needed was a quiet winter weekend (it's a very wintry book) and a melancholic nostalgia for the act of shared creation. And now I feel equipped to continue reading Cloud and Ashes, which is ... set in the world of Cloud, or tells tales from Cloud, or is simply a layer below the stories in Moonwise.

Unaccountably not available as an ebook: I do own the paperback, but reading physical books is increasingly uncomfortable on the eyes, so I resorted to the Internet Archive.