I should start by saying I'm pretty easy prey for somebody writing a book about Hollywood(land) in the early part of the 20th century. It has always intrigued and excited me. So, it was no surprise that I was waiting for this book to come out as soon as they announced the future release date of it. And I wasn't disappointed.

There were so many "crimes of the century"in the 20th century - the Lindbergh baby kidnapping, the Hall/Mills murders, the Leopold/Loeb murder case, the Black Dahlia, and fairly regularly right on up to O.J.Simpson.

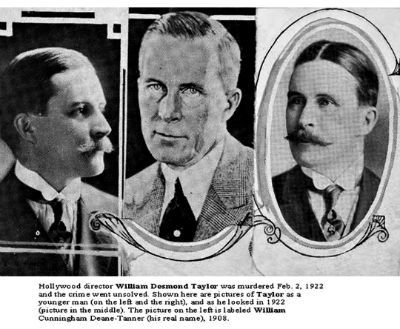

One of the first crimes of the century was the murder of movie actor/director/producer William Desmond Taylor, which remains unsolved to this day. It has everything a crime needs to grab the public's attention: movie stars, millionaires, barely credible eye-witnesses, sex, strict mothers of jazz-baby starlets...and, lots and lots of money.

There have been four books (to my knowledge - they could, of course, be more that I haven't discovered!), all taking very definite stands on why four completely different suspects were the "true" guilty party. On final analysis, what I really like about "Tinseltown: Murder, Morphine and Madness at the Dawn of Hollywood" is that Mann brings out all the suspects, gives all the reasons they would/could/should have done it - and all the reasons they couldn't have done it. He doesn't pretend to have a crystal ball and is able to solve a hundred year old murder case and call it a day.

Often, true crime books are remarkably dry and not very fun reading. This books is fun. Because of the cast of characters, there is room for lots of juicy Hollywood(land) gossip about the people involved and those who traveled in their individual circles. It almost reads like a novel - there is a chronological organization to the book that makes it seem like a story. Which is not to say that it's not filled with the prerequisite police reports and coroner reports, etc. - only that it's written for the reading public and doesn't try to be a forensics class textbook.

There were twelve suspects whose names were given to the news media as serious contenders for arrest (none ever were). The chief suspects were:

Convicted forger, embezzler and serial army deserter, Edward F. Sands, who spoke with a feigned (and poor) Cockney accent and worked as Taylor's valet until 7 months before the murder. While Taylor was in Europe, Sands forged his name on checks and burglarized his home (leaving footprints from Taylor's bedroom window to his own lodgings above the garage). After the murder, he was never heard from again.

Henry Peavy, who replaced Sands as Taylor's valet wore flashy golf ensembles - but didn't own clubs or play golf. He had a criminal record, and just three days before the murder was arrested for "lewd and dissolute" behavior. He died in 1931 of syphilis related dementia.

Mabel Normand was a popular comedic actress and frequent costar with Charlie Chaplin and Roscoe Arbuckle. According to author Robert Giroux, Taylor was deeply in love with Normand, who had originally approached him for help in curing her cocaine dependency. Based upon Normand's subsequent statements to investigators, her repeated relapses were devastating for Taylor. According to Giroux, Taylor met with Federal prosecutors shortly before his death and offered to assist them in filing charges against Normand's cocaine suppliers. Giroux expresses a belief that Normand's suppliers learned of this meeting and hired a contract killer to assassinate the director. According to Giroux, Normand suspected the reasons for her lover's murder, but did not know the identity of the triggerman.

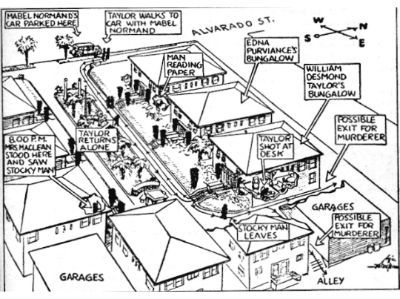

On the night of his murder, Normand left Taylor's bungalow at 7:45 pm in a happy mood, carrying a book he had given her as a loan. They blew kisses to each other as her limousine drove away. Normand was the last person known to have seen Taylor alive. The Los Angeles Police Department subjected Normand to a grueling interrogation, but ruled her out as a suspect. Most subsequent writers have done the same. However, Normand's career had already slowed and her reputation was tarnished by revelations of her addiction, which was seen as a moral failing. According to George Hopkins, who sat next to her at Taylor's funeral, Normand wept inconsolably throughout the ceremony.

Ultimately, Normand continued to make films throughout the 1920s. She died of tuberculosis on 23 February 1930. According to her friend and confidant Julia Brew, Normand asked near the end, "Julia, do you think they'll ever find out who killed Bill Taylor?"

Mary Miles Minter was a former child star and teen screen idol whose career had been guided by Taylor. Minter, who had grown up without a father, was only three years older than the daughter Taylor had abandoned in New York. Love letters from Minter were found in Taylor’s bungalow. Based upon these, the reporters alleged that a sexual relationship between the 49-year-old Taylor and 19-year-old Minter had started when she was 17. Robert Giroux and King Vidor, however, dispute this allegation. Citing Minter's own statements, both believed that her love for Taylor was unrequited. Taylor had often declined to see Minter and had described himself as too old for her.

However, facsimiles of Minter's passionate letters to Taylor were printed in newspapers, forever shattering her screen image as a modest and wholesome young girl. Minter was vilified in the press. She made four more films for Paramount, and when the studio failed to renew her contract, she received offers from many other producers. Never comfortable as an actress, Minter declined them all. In 1957, she married Brandon O. Hildebrandt, a wealthy Danish-American businessman. She died in wealthy obscurity in Santa Monica, California on 4 August 1984.

Charlotte Shelby was Minter’s mother. Like many "stage mothers" before and since, she has been described as consumed by wanton greed and manipulation over her daughter's career. Mary Miles Minter and her mother were bitterly divided by financial disputes and lawsuits for a time, but they later reconciled. Shelby's initial statements to police about the murder are still characterised as evasive and "obviously filled with lies" about both her daughter's relationship with Taylor and "other matters".

Perhaps the most compelling bit of circumstantial evidence was that Shelby allegedly owned a rare .38 calibre pistol and unusual bullets very similar to the kind which killed Taylor. After this later became public, she reportedly threw the pistol into a Louisiana bayou. Shelby knew the Los Angeles district attorney socially and spent years outside the United States in an effort to avoid official inquiries by his successor and press coverage related to the murder. In 1938 her other daughter, actress Margaret Shelby (who was by then suffering from both clinical depression and alcoholism), openly accused her mother of the murder during an argument. Shelby was widely suspected of the crime and was a favourite suspect of many writers. For example, Adela Rogers St. Johns speculated Shelby was torn by feelings of maternal protection for her daughter and her own attraction to Taylor. Although (like Sands) Shelby feared being tried for the murder, at least two Los Angeles county district attorneys publicly declined to prosecute her.Almost twenty years after the murder, Los Angeles district attorney Buron Fitts concluded there wasn't any evidence for an indictment of Shelby and recommended that the remaining evidence and case files be retained on a permanent basis (all of these materials subsequently disappeared). Shelby died in 1957.

And that's just the beginning of a long list of fascinating and shady/exotic characters that populate this story. Even William Desmond Taylor, the victim, had abandoned his family, changed his name, and went to Hollywood(land) to start a new life with a new identity.

I heartily recommend this book to anybody who is fascinated with cold-case unsolved murders, jazz-age Hollywood at it's nouveau riche gaudiest, or shady underworld characters and denizons of the sordid side of the movie business.