What do you think?

Rate this book

187 pages, Paperback

First published May 29, 2013

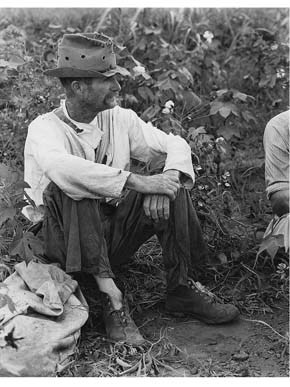

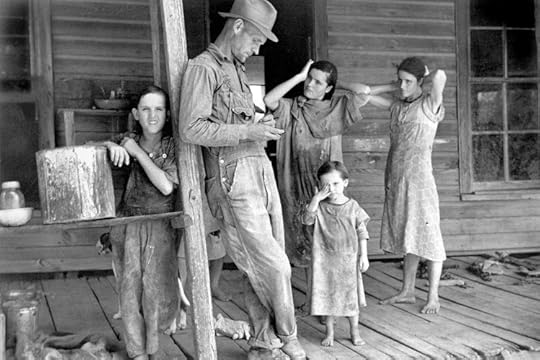

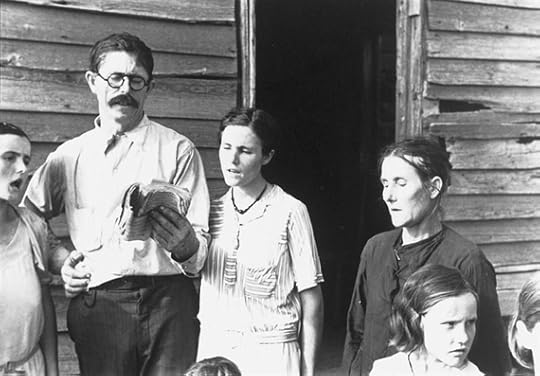

James Agee never lacked for recognition as a poet, film critic, or screenwriter. So much more was expected of him, though. He couldn't shake the suspicion that his talent was wasted even before his health wound down. "Nothing much to report," he wrote in a May 11, 1955, letter. "I feel, in general, as if I were dying: a terrible slowing down, in all ways, above all in relation to work." When he succumbed five days later, he was forty-five. It would be three more years before his novel A Death in the Family appeared and won its enduring acclaim. It had been a long time since anyone had mentioned his obscure book about tenant farmers in Alabama, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.